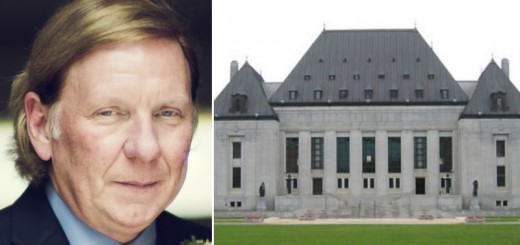

On Russell Brown’s Appointment to the Supreme Court of Canada

Today marks Justice Russell Brown’s official welcoming ceremony (you can watch the ceremony online here), and yet, I highly doubt Justice Brown feels welcome. His appointment has caused a flurry—no, a torrent—of public disapproval, online frustration on the politicization of the judiciary, and think-pieces on the demise of the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”). Some have called for a constitutional challenge to judicial appointments (if only Rocco Galati had his own bat-signal), while others have used the momentum from all the furor to explore more theoretical implications.

And yet, none of the criticisms are founded on much. Let’s look through a few:

Some of the criticisms stem from the fact that Justice Brown is not from Saskatchewan, making it a long 42 years since the SCC has seen a judge from the land of the living skies (the last one was Justice Emmett Matthew Hall). There has been a somewhat loose tradition of province rotation, where provinces take turns to fill up the SCC seats that remain after the three Quebec seats and three Ontario seats have been filled—but even calling this a tradition is giving it too much credit. The tradition does not seem to have much force. Many complained about this same issue when Justice Cromwell was appointed from Nova Scotia, once again overlooking Newfoundland (Newfoundland still has never seen an SCC judge from their ranks), but there is certainly no legal requirement that the Executive adhere to this principle of rotation. I think on this point it is safe to say this ‘tradition’ is no longer much of a tradition at all.

Another consistent criticism is Justice Brown’s relative lack of judicial experience. Justice Brown was appointed to the Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta in 2013, and then to the Court of Appeal of Alberta in 2014. That gives him about two and a half years of judicial experience. However, this is two and a half years more than both Justice Sopinka and Justice Binnie, appointed by Prime Ministers Mulroney and Chrétien, respectively. They were both appointed straight from private practice, with zero judicial experience. Justice Brown also has about the same appellate judicial experience (which is arguably more applicable to SCC work) as Justices Major and Bastarache, and more judicial experience overall than both of them. Of course, Justice Côté was appointed straight from private practice, too. Justice Brown’s judicial experience, or lack thereof, is no less than a number of great legal minds who proved themselves to be competent and able judges without much prior judicial experience.

But the biggest source of concern seems to spring from Justice Brown’s provocative digital trail. Writing for a University of Alberta faculty law blog between 2007 and 2008, “Russ Brown” expressed a number of controversial opinions, many of which have now been deleted (and, since only two people have the authority to delete these blogposts—the original author or the Vice-Dean of the law faculty, Moin Yahya—we can presume it was Justice Brown himself doing the spring cleaning). Among the highlights:

- Calling Justin Trudeau unspeakably awful: “As someone who hopes the Grits just fade away by the next election, I’m cheering for Justin Trudeau or Joe Volpe. Or have I missed a possible candidate who is as unspeakably awful?”

- Wishing Harper would get a majority: “I do hope Harper gets a majority and reforms the Canada Elections Act, starting with those odious third party spending limits.”

There are numerous other examples, collected by numerous news agencies. Peruse at your pleasure.

Justice Brown has left a digital trail on our very own TheCourt.ca as well. Justice Brown has twice posted on our website, and left numerous comments, usually tort-related, on a variety of posts from February 2007 to as recent as March 2012.

The most interesting of these comments are those where Justice Brown comments on the judicial process itself, as a curious look into what pre-SCC-appointment Justice Brown thinks of the role he did not yet know he would occupy.

- In one, he offers comments on the need for a public debate among judges through dissenting opinions, though he does caution that too many dissenting opinions can lead to “competing masters’ dissertations.”

- In another, he questions the requirement that candidates for appointment to the SCC be bilingual, arguing that it would considerably shrink the pool of qualified candidates.

- Here, Justice Brown expresses confusion as to why Harper bypassing the judicial committee when electing Justice Cromwell in 2008 would be a blow to judicial independence, as the author of the post claims.

- In this one, Justice Brown proclaims that there are no Albertan judges on the court, and Beverley McLachlin (who grew up in Alberta but only sat on BC benches) is as much from Alberta as Iacobucci is from BC (he grew up in BC but was an Ontario appointment) – aka, not at all.

- Lastly, this one, which criticizes the SCC as “one of the weaker Anglo-American high courts in the field of tort law.”

None of these comments are “provocative.” They are interesting only insofar as they show the inner working of Justice Brown’s thoughts and opinions on the court that he would soon, though unbeknownst to him, sit on.

It is rare that we get such an inner look into an SCC judge. But what can we take from these comments and blogposts?

At the time of all of these posts, Justice Brown was a member of the University of Alberta Faculty. Justice Brown only began his judicial career in February of 2013. Justice Brown has never spoken about the content of these posts or why he took them down. However, at the time of his writing, Justice Brown occupied a distinct role as an academic (and did so quite well, if his high scores on RateMyProfessor are any indication), in a sphere where prolific writing was encouraged, and bold stances protected. Is it fair to then pounce on those pronouncements once he has a career change?

It would be an opportune time among all this hubbub to revisit the question Justice Sopinka posed in 1996: must a judge be a monk?

Sopinka answered this with a resounding no, though he posed this question in response to concerns about current judges taking speaking appointments and then being rebuked for the content of those speeches (see Sopinka, “Must a Judge Be A Monk – Revisited” 45 UNBLJ 167 1996). But Sopinka’s question can equally apply to comments made before a judge became a judge.

Sopinka says: “Total abstention from political discussion will transform judges into social eunuchs” (170). Expecting an abstention from political discussion even before the judge is a judge is even more restrictive.

Carissima Mathen, an Associate Professor at the University of Ottawa, agrees that demanding a life-long and pre-appointment monastic lifestyle from our judges is problematic.

“I’m more comfortable with a person who has pursued a career to their fullest and is not in the back of their mind weighing every public appearance with how it might look when they are a judge,” she says. “We have to be very careful not to encourage people to be ciphers … Otherwise, very intelligent people will be inhibited in participating in public discourse.”

Eugene Meehan QC, lawyer at Supreme Advocacy LLP in Ottawa and former Executive Legal Officer of the Supreme Court of Canada, thinks we should go even further – paper trails should be considered an asset rather than a disqualification when considering someone for a judicial role. He wrote in an email: “Having an online-presence before [Justice Brown] was appointed a Judge in fact demonstrates he was both in touch with what was going on, and was accessible about his then views. These days, that’s not a negative, it’s a plus.”

But where is the line to be drawn? Surely judicial candidates can’t say anything they want and still expect a spot on the bench. Ms. Mathen believes the line should be drawn at “comments that are intolerant, that pull against the values of Canadian society,” that are bigoted or display bias against particular groups. But when it comes to “straight discussion of policy,” Mathen thinks the line is more “inclusive than exclusive.”

Justice Brown’s comments do express strong views, but most of them lie on the side of policy. None of them are intolerant, and the opinions on political candidates? They are within his role as an academic and his right as a Canadian to express those opinions, whether or not we agree with them.

Unfortunately, not many share the opinions of Mathen and Meehan. While Justice Brown’s comments show that he was not censoring himself for fear of how he may appear in a future where he is a judge, many do not see this as an asset (and since Justice Brown himself likely deleted the posts, perhaps he didn’t see them as one either).

If the rotating-province tradition hasn’t been a tradition for a while now, if there has never been much correlation between judicial experience and actual judicial competency, and if a judge should not have to join monk-dom either before or during his judge-hood, from where does all this concern from critics come?

And the critics are vociferous. The wonderful blog Policy Options has a whole section on debating judicial appointments in light of Justice Brown’s, with articles from heavy-hitters like Jamie Cameron, Leonid Sirota, and Dean Lorne Sossin. Many of the articles are fantastic, providing unique angles on judicial appointments in Canada, and meta-commentary on the critiques – I highly recommend you take a look. But many more contribute to the ongoing critiques of Justice Brown as an individual. And that is the problem.

Without being trite, it is clear that all the furor over Justice Brown’s appointment is only tangentially related to Justice Brown himself. It goes back farther and deeper than just this appointment. The concern is that this appointment is the symptom of a much bigger problem—the “closing of the Canadian mind,” as the New York Times article put it, by a certain Stephen Joseph Harper.

With seven of the nine judges as Harper appointees, it may be hard not to fear a stacking of the court, particularly in the face of fears that future appointments will become even more secretive than the “news release” appointments we have now. Others fear that an increasingly conservative court will cause the Charter to be rolled back. But if Harper has been plotting a conservative court, it hasn’t worked much in his favour so far. The current Harper-appointed court has not pandered to the government, and in fact has opposed many government-led initiatives, including Nadon’s appointment, provisions against medically-assisted suicide, Senate reform, and anti-prostitution laws. If Justice Brown can singlehandedly convince eight other judges that they should start deferring to the Executive, which they have not yet been convinced to do, then Justice Brown is even more deserving of this appointment. But that is unlikely, and his unique perspective—one not shared by the majority of Canadians, to be sure—does add ideological diversity to the court.

Meehan says, “The range of legal issues the Supreme Court deals with, you need a range or people and personalities as well as backgrounds and experiences. Nine bland clones – which this court is most definitely not – is useful to no one.”

This Supreme Court is a particularly strong one – they are butter, not margarine. Justice Brown’s diverse experience is a strength that will fit with an already-strong court. They are accessible, interviewable, and on TV – and that inevitably attracts both attention and criticism – as a Supreme Court Judge, some days you’re a pigeon, some days a statue.

It’s a shame that Justice Brown had to be welcomed in today as a statue. But I am doubtful that his appointment will usher in an era of conservative deference. It is, of course, integral that Harper make judicial appointments more transparent. And we do have a right to know why Justice Brown was picked over all the other qualified candidates. But the critics arguing that Justice Brown is himself an unjustifiable candidate have no solid arguments to back them up.

Join the conversation