Appeal Watch: Crown must increase annual payments to its Anishinaabe treaty partners in Restoule v Canada

In 1850, the Anishinaabe of the upper Great Lakes agreed to share their vast territory in exchange for hunting and fishing rights, as well as an annual payment (“annuity”) from the Crown. The Crown promised that the annuities could increase over time so long as resource development in the area proved profitable. Mining and forestry eventually did flourish, but the annuities increased just once, almost 150 years ago. To this day, the Anishinaabe receive a couple of toonies every year for each of its members as billions of dollars’ worth of precious metals, lumber, and other goods are taken from their lands.

In Restoule v Canada, 2021 ONCA 779 [Restoule], the Ontario Court of Appeal (“the Court”) unanimously held that the Crown has neglected its treaty promises for far too long. This case comment reviews the Court’s reasons and discusses why the standard of review for treaty interpretation could be the central issue before the Supreme Court of Canada in a subsequent appeal.

Background

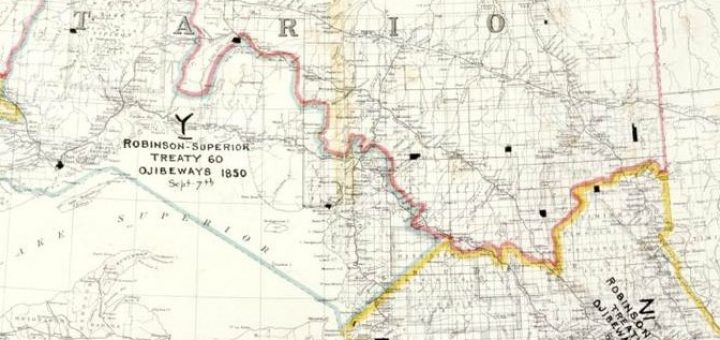

The Robinson-Superior and Robinson-Huron Treaties (“Robinson Treaties” or “Treaties”) cover a stretch of northern Ontario from just west of Thunder Bay to the border with Quebec (Restoule, para 11). The need for a treaty became apparent in the mid-1840s when the Anishinaabe Chiefs demanded compensation for mining activities that were starting to encroach on their territory (Restoule, para 33). A Treaty Council was eventually held in Bawaating (Sault Ste. Marie) and Garden River, in both English and Anishinaabemowin (Restoule, para 48). The Crown offered an annuity that was less than half of what First Nations in southern Ontario received. This was both because of the as yet unknown value of the land and because Canada was in a financial crisis at the time (Restoule, paras 43-45). After some initial resistance from the Huron delegation, the Treaties were finalized by September 9, 1850 (Restoule, paras 55-57).

The key terms of the Treaties may be summarized as follows:

- The Anishinaabe would receive a “perpetual annuity … to be paid and delivered to the said Chiefs and their tribes.”

- The annuity would be augmented from time to time if resource-based revenue from the territory was enough to avoid a net loss to Crown, provided that,

- The individual payments did not exceed one pound in a given year, “or such further sum as Her Majesty may be graciously pleased to order,” and

- The population did not drop below two-thirds of the number of beneficiaries at the time the treaty was formed, in which case the annuity would need to be reduced (Restoule, paras 61-63).

The annuity was increased, for the first and last time, to $4 per person in 1875 (Restoule, para 67).

Trial Decision

The trial was split into three stages. The first dealt with interpreting the treaty (Restoule v Canada, 2018 ONSC 7701, “Stage One”). The second took up the Crown’s defences, which the trial judge rejected (Restoule v Canada, 2020 ONSC 3932, “Stage Two”). The third stage will focus on remedies and the allocation of liability between Ontario and Canada.

The Court of Appeal focused primarily on the Stage One judgment. There, the trial judge found that the annuity has both a collective and individual dimension (Restoule, para 73). She interpreted the augmentation clause as a promise that the Crown would increase the collective annuity where the resource-based revenue of the territory permits it to do so without incurring a loss, subject to a $4 per capita limit on individual distributive payments (Restoule, para 70). She concluded that the Crown’s obligation to increase the annuities in these circumstances is a mandatory and reviewable one, but the Crown retains discretion over how to implement the augmentation promise, including whether to increase the individual payment beyond the $4 per capita limit (Restoule, paras 70, 194). The Stage One judgment issued a series of declarations reflecting these findings. The declarations also confirmed that the augmentation promise is a constitutionally recognized treaty right under section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982 [Constitution].

Appellate Decision

Only Ontario appealed the judgments from the lower court. The province raised eight issues pertaining to Stage One. This case comment examines two of them: the standard of review for treaty interpretation, and the trial judge’s interpretation of the augmentation clause. In brief, most of the judgment was upheld. The few amendments the Court made to the declarations will affect the litigation of remedies at Stage Three. The changes do not substantially alter the nature and scope of the treaty promises the trial judge identified in Stage One.

A majority of the Court held that the standard of review is correctness

Chief Justice Strathy and Justice Brown (Lauwers J. concurring) held that the standard of review for interpreting treaties is correctness. This is a less stringent standard. It accords no deference to the trial judge’s findings, enabling an appellate court to substitute its own opinion. Chief Justice Strathy and Justice Brown rely here on R v Marshall,[1999] 3 SCR 456 [Marshall]. In Marshall, a majority of the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) set out that the inferences and conclusions the trial judge had drawn from the historical record concerning treaties from the 1760s invited the same standard of review that was applied to the scope of an Aboriginal right in R v Van der Peet, [1996] 2 SCR 507 [Van der Peet] (Marshall, para 18). That standard was correctness.

The plaintiffs submitted that the deferential standard of palpable and overriding error that the SCC applied to contracts in Sattva Capital Corp v Creston Moly Corp, 2014 SCC 53 [Sattva] ought to apply to treaties as well (Restoule, paras 398-400). Chief Justice Strathy and Justice Brown dismissed this argument. They point out that a year after Sattva was decided, the SCC referenced both Marshall and Van der Peet in concluding that the standard of review was correctness for a constitutional document regarding legislative bilingualism (Caron v Alberta, 2015 SCC 56 at para 61).

The Chief Justice and Justice Brown offer two policy arguments as well, the first being that treaties are sui generis agreements between the Crown and Aboriginal peoples, limiting the relevance of contract law and therefore cases like Sattva (Restoule, paras 406-07). Second, they write that interpretations of the Robinson Treaties have precedential value for future generations, as the agreements were meant to last indefinitely (Restoule, paras 408-10). As such, even if Sattva were relevant, it would be limited by the rule in Ledcor Construction v Northbridge Indemnity Insurance Co, 2016 SCC 37, which established that contracts of precedential value must be reviewed on a standard of correctness.

The dissenting judges would have held that the standard of review is palpable and overriding error

Justice Hourigan (Pardu J. concurring) would have applied the more stringent standard of palpable and overriding error. This standard shows much greater deference to the trial judge’s findings on questions of fact and of mixed fact and law. Justice Hourigan declined to take up the plaintiffs’ approach of applying Sattva, agreeing with the majority that the analogy to contract law is not entirely on point (Restoule, paras 510-13). Instead, the decisive factor for Hourigan J.A. is that the interpretation of historical treaties requires extensive factual findings to offset certain problems inherent in relying on the written agreement alone (Restoule, paras 521-28). Examples of such problems include the reduced bargaining power of Indigenous peoples in the 19th century, as well as cultural, linguistic, and philosophical differences between the parties.

Justice Hourigan underscores that the trial judge must sift through a mountain of evidence and select from competing views of what happened (Restoule, paras 568-73). The very existence of competing accounts belies the notion of a singular, “correct” interpretation (Restoule, para 571). Justice Hourigan rejects the line that Van der Peet and Marshall draw between finding historical facts and drawing inferences and conclusions from those facts. He writes instead that the fact-finding, inference-drawing, and conclusion-making required for interpreting the parties’ common intention at the time of forming the treaty are “usually two sides of the same coin” (Restoule, para 558).

In response to the majority, Justice Hourigan notes that the authoritative case on appellate standards of review, Housen v Nikolaisen, 2002 SCC 33 [Housen], was decided after Van der Peet and Marshall. Looking at Housen, it may be more appropriate to say that the correctness standard was appropriate in Van der Peet and Marshall because they concerned pure questions of law: the test for an Aboriginal right on the one hand, and the role of the honour of the Crown in treaty interpretation on the other (Restoule, para 559). Justice Hourigan dismissed the majority’s second policy argument by noting that the Robinson Treaties are the only ones in Canada to contain augmentation clauses for their annuity payments. This peculiarity thus negates the Treaties’ purported precedential value (Restoule, para 557).

A majority of the Court found that there were no errors in the trial judge’s interpretation of the Treaties

All five justices agree that the objective of treaty interpretation is to identify the common intention of the parties that best reconciles the interests of both sides at the time of entering the treaty (Restoule, paras 107, 451). They also agree that the principles of treaty interpretation include an examination of the words of the agreement as well as the context in which it was negotiated (Restoule, paras 108-09, 388, 420-21). The majority and minority diverge, however, in the relative emphasis they place on text and context in constructing the common intention of the parties. This may explain why they reached opposite conclusions regarding the trial judge’s interpretation of the augmentation clause.

The majority—consisting of Lauwers and Pardu JJ. (Hourigan J.A. concurring)—held that the trial judge did not make any reversible errors. The justices write that “extrinsic evidence is always available to interpret historical treaties” (Restoule, para 108). Further, they write that the examination of such evidence, including the cultural and linguistic differences of the parties, need not wait until ambiguities are discerned in the text of the treaty (Restoule, paras 109-110). In support of this approach, the majority cite both opinions in Marshall as well as the Court’s decision in R v Taylor and Williams, (1982) 34 O.R. (2d) 360.

In this vein, the majority highlights the trial judge’s attentiveness to the Anishinaabe perspective in her analysis of the parties’ common intention. The trial judge found that for the Anishinaabe, treaties are not one-time transactions, but rather relationships over time governed by the norms of respect, responsibility, and reciprocity (Restoule, paras 115-16). This grounds the trial judge’s conclusion that the interpretation of the augmentation clause that best reflects a treaty relationship is the one that recognizes both a collective annuity that increases where the economic circumstances permit it, and a cap on individual payments (Restoule, para 122).

A minority of the Court would have held that the trial judge’s interpretation was not supported by the text of the Treaties

Unlike the majority, Strathy C.J.O. and Brown J.A. emphasized the words of the Treaties, referencing Marshall for the proposition that treaty interpretation must begin with the specific words of the agreement, followed by an identification of any ambiguities or linguistic and cultural misunderstandings. The two stages establish a preliminary framework for examining the historical evidence (Restoule, paras 420-21).

Per Strathy C.J.O. and Brown J.A., the trial judge erred in law “because she never gave the language of the Robinson Treaties a fair opportunity to speak” (Restoule, para 419). In their view, a collective annuity could not be supported on a plain reading of the text. Instead, they conclude that the correct interpretation of the parties’ common intention was that the augmentation clause created a “soft cap” on the per capita annuity (Restoule, para 431). This “soft cap” is subject to the Crown’s discretion to increase the per capita amount from time to time. The Crown’s discretion is not unfettered; it must turn its mind to the prospect of increasing the annuity, provided that resource-based revenues from the territory permit an increase without incurring loss (Restoule, paras 498-506).

Discussion

Despite disagreeing about the trial judge’s interpretation of the treaty, the justices unanimously held that the Crown has an obligation to apply the augmentation clause from time to time. With six justices having now ruled against the Crown, it is possible that Ontario will forego any further appeals and focus its efforts on Stage Three. On the other hand, Strathy C.J.O. and Brown J.A. define the obligation in terms more favourable to the Crown—a requirement to consider increasing the annuity offers more leeway than a requirement to actually increase it. Chief Justice Strathy and Justice Brown would not have been able to substitute their “soft cap” interpretation of the augmentation clause if they had applied the standard of palpable and overriding error. This may give Ontario an incentive to pursue the issue on appeal. It is certainly true that the standard of review was the most contentious issue in this decision.

On this point, I found Justice Hourigan’s reasons more convincing. Especially compelling was the point that both Van der Peet and Marshall came out before Housen, the authoritative case on appellate standards of review. In Housen, the majority reasoned that questions of mixed fact and law should be accorded a higher level of deference owing to the difficulties of extricating factual and legal inferences, as well as the fact that both are intertwined with weighing the evidence, which is typically the prerogative of the trial judge (Housen, paras 26, 32). This resonates with Justice Hourigan’s point that when determining the common intention of the parties, historical fact-finding and the drawing of inferences and conclusions from those facts are interrelated. Separating them into two stages is an artificial exercise. In any event, Housen established that extricable questions of law must be treated on a standard of correctness (Housen, para 36). To the extent that Strathy C.J.O. and Brown J.A. were most perturbed by the trial judge’s lack of attention to the text of the Treaties, this could have been handled as an extricable error of law under the Housen framework.

In addition, the policy arguments for deference set out in Housen apply with equal force to treaty cases (Housen, paras 15-18, 32). The critical one is that the trial judge is in an advantageous position relative to the appellate court in terms of receiving, reviewing, and weighing the evidence. As Justice Hourigan points out, the trial judge in this case sat for 67 days in addition to 11 days of closing submissions (Restoule, para 569). There were over 30,000 pages of historical documents, as well as eleven expert witnesses (Restoule, para 569). In addition, the trial judge took special care to conduct the proceedings in a manner reflecting the customs, traditions, and knowledge practices of the Anishinaabe plaintiffs (Restoule paras 575-76). The Court of Appeal heard submissions from the parties and interveners over eight days for this case, an exceptionally long hearing, but one that does not come close to replicating what happened at trial.

Finaly, out of fairness to future Aboriginal rights litigants, it is important that the SCC settle the issue of the standard of review for treaty interpretation. In a decision from earlier this year, a majority of the SCC encouraged Aboriginal claimants to pursue their s. 35 claims through civil actions, in part so that appellate courts can have the benefit of extensive evidentiary findings (R v Desautel, 2021 SCC 17 at para 90). Section 35 claims require an enormous amount of time and resources to succeed at trial. When they do, they tend to result in heavy obligations for the Crown, making appeals more likely. Plaintiffs contemplating an action ought to know how vulnerable the trial judge’s findings may be on appeal.

(Photo: Ontario, Department of Surveys, James L Morris, “Map of the province of Ontario: Dominion of Canada. Map No. 20a” (1931), Archives of Ontario, IOO22329 [image has been cropped].)

Join the conversation