Orphan Well Association v Grant Thornton Ltd: Constitutional Doctrines Applied to Cleaning Up Old Oil Wells

Introduction

On January 31, 2019, the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC” or “the Court”) reached a decision on bankruptcy and insolvency law and the obligations owed by oil and gas companies that have filed for bankruptcy. The ruling raises policy implications for secured lenders and. insolvency professionals. It also answered the question of which entities should be responsible for the cost of cleaning up abandoned oil wells.

In Orphan Well Association v Grant Thornton Ltd, 2019 SCC 5 [Orphan Well], the SCC overturned the decisions of the Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench (“ACQB”) and the Alberta Court of Appeal (“ABCA”) and clarified the interpretation of certain provisions in the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act, RSC 1985, c B-3 [BIA], the Oil and Gas Conservation Act, RSA 2000, c O-6, and the Pipeline Act, RSA 2000, c P-15. The key legal issue raised in the case was how to reconcile the various statutes implicated, which Grant Thornton claimed conflicted. The doctrine of paramountcy establishes that federal legislation supersedes any provincial counterpart when each respective law is valid, but the laws are inconsistent or conflicting. While the lower courts interpreted and reconciled provisions from the statutes by applying the doctrine of paramountcy, the SCC held that the doctrine of paramountcy did not apply in this case and no conflict existed between the provisions at issue.

Background

According to Alberta law, a company that exploits oil and gas resources in Alberta must hold a property interest in the oil or gas, surface rights and a license issued by the Alberta Energy Regulator (“Regulator”) (Orphan Well, para 9). Under these provincial rules, the Regulator can only grant a license if the licensee assumes certain end-of-life responsibilities for its oil and gas assets. Such responsibilities include the plugging and capping of oil wells to prevent leaks, dismantling surface structure and restoring surfaces to their previous conditions. These are environmental obligations are known as “abandonment” and “reclamation” (Orphan Well, para 9).

Redwater Energy Corporation (“Redwater”) was a publicly traded oil and gas company in Alberta, which had 127 principal oil and gas assets. These assets included wells, pipelines and facilities and their corresponding licenses. Redwater suffered financial difficulty in 2014 and went into receivership in May 2015, and appointed Grant Thornton Limited (“Grant Thornton” or “the Respondent”) as its receiver. In addition to undertaking the role of receiver, Grant Thornton was deemed to be the licensee of Redwater’s oil and gas assets. Subsequently, it was notified by the Regulator that it was legally required to fulfill the abandonment obligations for Redwater’s licensed oil and gas assets prior to distributing anything owed to creditors.

Critically, Grant Thornton informed the Regulator that it was unable to meet the end-of-life obligations for the spent wells, as the cost of doing so was likely to exceed the proceeds of sale for the wells. To avoid such costs, Grant Thornton decided to renounce the unproductive wells, stating that the BIA allowed for this. Nevertheless, it took possession and control of 17 of Redwater’s most productive wells, 3 associated facilities and 12 associated pipelines.

Contrary to Grant Thornton’s interpretation of the BIA, the Regulator took the position that neither the BIA nor provincial law allowed Grant Thornton to disown the licensed assets. Grant Thornton argued that even if it had to abide by the abandonment orders issued by the Regulator, such orders were considered “provable claims” under the BIA. This meant that Grant Thornton would first have to pay off any creditors before fulfilling obligations under the abandonment orders (Orphan Well, para 50)

Judicial History

The ACQB agreed with Grant Thornton in holding that a trustee could renounce its oil and gas assets and that any end-of-life obligations would be considered as “provable claims” under the BIA. The Alberta Court of Appeal upheld this decision (Orphan Well, paras 54-62).

SCC Decision

In a 5-2 majority decision, the SCC held that the doctrine of paramountcy does not apply on these facts and that both the BIA and Alberta’s provincial regime can co-exist without any conflict. By overturning the lower court decisions, the SCC held that the BIA provisions aimed to protect trustees only from being personally responsible to pay for an estate’s environmental obligations.

Majority

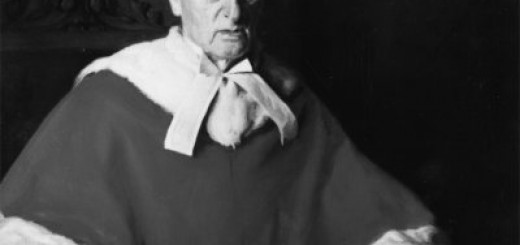

Chief Justice Wagner wrote the decision for the majority. He found that the provincial Regulator’s enforcement of the end-of-life obligations against Redwater did not violate the doctrine of federal paramountcy. In doing so, he undertook an extensive analysis of the doctrine.

The doctrine of paramountcy applies in situations in which the federal government passes valid law, the provincial government passes valid law, and the two laws conflict. A paramountcy analysis examines whether dual compliance with both federal and provincial legislation is possible, or whether the provincial legislation is incompatible with the purpose of the impugned federal legislation. If it is the case that the provincial legislation is incompatible with the federal law, the federal law will be upheld (will be “paramount”) and the provincial scheme will be struck down to the extent of the inconsistency.

Chief Justice Wagner mentioned under both branches of the paramountcy test, the party alleging the conflict bears the burden of proof to demonstrate that the test is met. He emphasizes however, that

[t]his burden is not an easy one to satisfy, as the doctrine of paramountcy is to be applied with restraint. Conflict must be defined narrowly so that each level of government may act as freely as possible within its respective sphere of constitutional authority…the application of the doctrine of paramountcy should also give due weight to the principle of co-operative federalism…While co-operative federalism does not impose limits on the otherwise valid exercise of legislative power, it does mean that courts should avoid an expansive interpretation of the purpose of federal legislation which will bring it into conflict with provincial legislation. (Orphan Well, para 66)

The specific provision at issue was section 14.06 of the BIA, which Grant Thornton interpreted to imply that “since it [had] disclaimed Redwater’s unproductive oil and gas assets, [the section] empower[ed] it to walk away from those assets and the environmental liabilities associated with them” (Orphan Well, para 4). Grant Thornton also asserted that the provincial legislation reorders the priorities of bankruptcy established by the BIA, which prefer repayments to secured creditors over ordinary creditors.

After a lengthy exercise of statutory interpretation and a thorough investigation of the parliamentary transcripts and debates, the majority concluded that the impugned section is only concerned with personal liability of the trustee, and not liability of the bankrupt estate (Orphan Well, para 75). Grant Thornton was therefore still accountable for the environmental liability by ensuring compliance with the end-of-life regulations.

As for Grant Thorton’s second assertion regarding the priorities established by the BIA, the Court dissected the collective proceeding model which governs the equitable distribution of the bankrupt’s assets as proposed by the BIA (Orphan Well, para 115). The Court referred to the test provided in Abitibi to determine if a particular regulatory obligation amounts to a claim provable in bankruptcy. The test states

First, there must be a debt, a liability or an obligation to a creditor. Second, the debt, liability or obligation must be incurred before the debtor becomes bankrupt. Third, it must be possible to attach a monetary value to the debt, liability or obligation. (Orphan Well, para 119)

Chief Justice Wagner concluded that the first branch of the test was not met as the Regulator could not be considered a creditor. Rather, the Regulator had a statutory mandate to regulate the oil and gas industry. Furthermore, the Regulator did not stand to financially gain from recovering the debt. The Regulator’s end-game was to have the environmental work performed for the public and not for an intrinsic benefit. For these reasons, the provincial legislation in question was found not to conflict with the priorities established by the BIA in ranking which creditors to should paid off first.

It is interesting to note that Justice Sheila Martin, who was excused from this hearing, wrote the dissenting opinion in the ABCA decision and would have allowed the Regulator’s appeal. Chief Justice Wagner refers to her dissenting opinion on more than one occasion.

Dissent

Justice Cotȇ, along with Justice Moldaver, came to the opposite conclusion in their dissenting opinion. They found that the appeal should be dismissed and that there was an operational conflict that creates an inconsistency between the federal and provincial law.

Of particular note are the concerns raised by the dissenting judges regarding the potential for a chilling effect on financing within Alberta’s oil and gas sector. Justice Cotȇ summarizes the concern as follows:

If the estate’s entire realizable value must go toward its environmental liabilities, leaving nothing behind to cover administrative costs, insolvency professionals will have nothing to gain — and much to lose — by stepping in to serve as receivers and trustees, irrespective of whether they are protected from personal liability. Debtors and creditors alike, knowing that this is the case, will have no reason to even petition for bankruptcy. The result is that none of a bankrupt estate’s assets will be sold — not even an oil company’s valuable wells — and the number of orphaned properties will increase. (Orphan Well, para 221)

According to the dissent, this flies in the face of the original purpose of the BIA, which was to encourage insolvency professionals to accept mandates and to reduce the number of abandoned sites (Orphan Well, para 221).

Implications of SCC’s Ruling

This decision is a blow to secured creditors and lenders. In effect, the Court’s decision forces receivers and trustees to ensure that they have fulfilled their environmental obligations under the provincial rules before repaying debts to lenders. Prioritizing environmental security over prior debt obligations sends a strong message by the Court that provincially enacted environmental legislation cannot be ignored even in bankruptcy claims. The necessary consequence of this ruling will be fewer options to secure credit on such projects, or more expensive financing options to hedge against the increased risk of defaulting on payments.

As the dissent emphasized, the case will also impact insolvency professionals. The decision may potentially discourage insolvency professionals from accepting mandates if an estate’s entire realizable value must go towards its environmental liabilities. Such a situation will leave nothing left over as an incentive for the insolvency professionals to get involved in the first place.

The Orphan Well decision is great example of the application of constitutional doctrine in understanding the law. The Court grappled with sensitive political considerations concerning environmental legislation vis-à-vis the oil and gas industry in Alberta, but did so within the confines of established doctrines. The issue of abandoned wells is a real one and this decision affirms that environmental obligations can no longer simply take a back seat and remain ignored by the industry.

Join the conversation