Putting a Price On Lost Time: R v Mullins-Johnson

The Ontario government recently agreed to pay William Mullins-Johnson, a victim of wrongful conviction, a $4.25 million reward to compensate him for 12 years spent in prison. Stories like this tend to raise the question in our minds of “How does one put a price on lost time?” I will cover Mr. Mullins-Johnson’s acquittal at the Ontario Court of Appeal in 2007 and will take readers on a historical journey to determine what price governments have put on lost time to see if any patterns emerge. But I warn readers: I will not, and cannot answer the crucial question of how we price lost time.

R v Mullins-Johnson, 2007

Quite humbly and remorsefully, the Court of Appeal acquitted Mr. Mullins-Johnson in R v Mullins-Johnson, 2007 ONCA 720. The appeal arose from a Reference the Minister of Justice ordered on July 6, 2007. The Reference was directed to the Court pursuant to s. 696.3(3)(a)(ii) of the Criminal Code, RSC, 1985, c C-46 [Criminal Code], asking the Court to determine the case as if it were an appeal on the issue of fresh evidence. On this “appeal” two main issues were considered:

- What reasons existed to support the admission of fresh evidence?

- Should the Court go further and (in addition to an acquittal) declare Mr. Mullins-Johnson factually innocent?

Four year old Valin Johnson was found dead in her bed one morning in 1993. Doctors at both the Sault. Ste. Marie General Hospital and the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto assessed the situation. The initial findings by three doctors (one of whom is the now discredited Dr. Charles Smith) determined that the girl had suffered sexual abuse and died of homicidal asphyxiation. Since Mr. Mullins-Johnson had been babysitting at the estimated time of death, he was quickly arrested and charged with first degree murder and aggravated sexual assault.

However, the Association in Defence of the Wrongfully Convicted (“AIDWYC”) enlisted the help of an eminent pathologist, Professor Bernard Knight to contest this charge. Professor Knight requested information from Dr. Michael Pollanen, the Chief Forensic Pathologist for Ontario. Both doctors performed their own separate investigations, and discovered that the “signs” of abuse and murder were simply the result of normal processes following death or, (in some cases) were caused by procedures connected to the post-mortem autopsy. The doctors later met to substantiate their separate investigations and both concluded the initial evidence was incorrect.

O’Connor, A.C.J.O, writing for an unanimous court, determined that the evidence clearly met the test for admitting new evidence established in R v Palmer, [1980] 1 SCR 759. Further, he stated if the evidence had not met the Palmer test, the result in R v Maciel, 2007 ONCA 196 would apply, where Doherty J.A. stated, “Evidence should be received on appeal, regardless of whether it was available at trial…if the evidence is sufficiently cogent to warrant an acquittal.” Clearly in this situation, this evidence was extremely damaging to the prior conviction.

The Court then went on to consider the possibility of declaring Mr. Mullins-Johnson to be “factually innocent.” While the law only requires a finding of “not guilty” to support an acquittal, it was suggested that Mr. Mullins-Johnson be declared “factually innocent” as well. The main difference between these two characterizations is that a finding of factual innocence requires absolutely no reasonable belief an accused could have committed a crime. The Court of Appeal declined to make this statement, concluding that there are not two types of acquittals available in Canada. Their decision to deny the request stemmed from policy considerations, primarily, that the meaning of a “not guilty” verdict would be degraded to all others in the criminal system. A “higher” statement of “factual innocence” could cast doubt on the innocence of those receiving not guilty verdicts, thereby eroding the fundamental principle of criminal law: innocent until proven guilty.

Crunching The Numbers

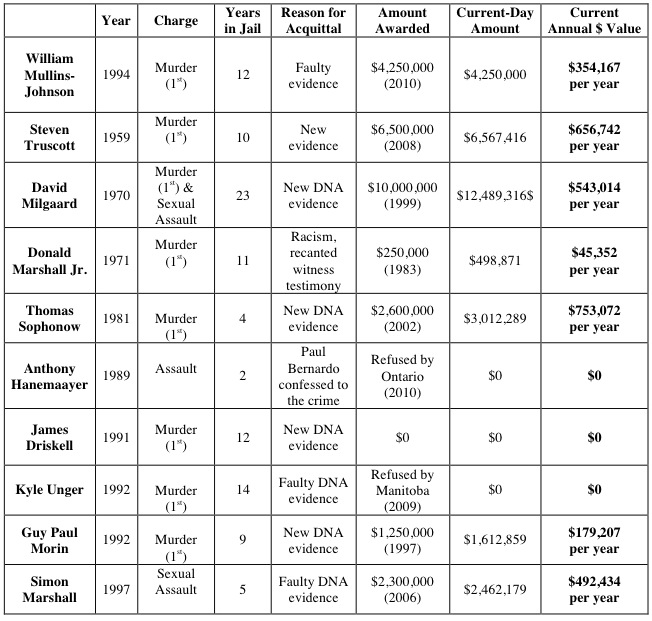

To the best of my knowledge, no publication exists in which compensation on an annual basis has been calculated for Canada. To arrive at these figures, I simply divided the total amount awarded by the number of years the accused spent in jail. Below is a chart I have created through my own research. Some of the most high-profile wrongful convictions were sampled for the purposes of this table.

* Disclaimer: This chart is not statistically significant as a result of the low sample size. Readers are welcome to comment for further information on the data collection and calculations found in this chart.

Before compiling this chart, I was certain patterns would emerge. Although unsure as to exactly what I would find, I assumed there might be some correlation between the reason for acquittal, years spent in prison and perhaps the initial charge and the victim’s damage settlement amount.

Was I ever wrong! Readers will notice that the length of time does not seem to have an obvious pattern. Rather discouragingly, some victims of wrongful conviction were denied settlement in any way. Claimants are able to engage in litigation in an attempt to recover compensation, but, of course this is costly and timely. Of those awarded some sort of compensation, the annual amount is extremely spread out, from about $45,000 per year to $753,000 per year! The data also shows no correlation between current awards and past awards – so no historical “improvement” can be inferred.

The Future of Wrongful Convictions in Canada

In a nutshell, it appears as if those who are wrongfully convicted have no way of predicting the amount of potential damage settlements. The answer to our question of “How much is one year is prison worth?” has no concrete answer. A huge range exists, and according to preliminary research, damage awards seem to be arbitrarily determined. Whatever the amount, though, I believe most would agree with me when I say there is no price you can put on one’s freedom. It is therefore in society’s best interest to address these deficiencies in the justice system and take all available steps to prevent these terrible miscarriages of justice.

Join the conversation