QCCA Says Prohibitions on Genetic Discrimination Are Not Valid Use of Federal Criminal Law Power

The Quebec Court of Appeal (“QCCA”) recently delivered its opinion in the Genetic Non-Discrimination Act Reference, [GNDA Reference], concluding that the Genetic Non-Discrimination Act, SC 2017, c.3 [GNDA] is beyond the scope of the federal criminal law power. The Act, which was introduced by Senator James Cowan, was passed by Parliament in 2017. Shortly after its passage, the Quebec government initiated a reference asking the QCCA whether the Act was a valid exercise of the criminal law power. In an unusual turn of events, the Attorney General of Canada joined the Attorney General of Quebec in arguing that the Act was beyond the scope of s.91(27) (the criminal law power) of the Constitution Act, 1867.

Nine days after hearing oral submissions, the QCCA issued its opinion in late December. An appeal as of right lies to the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) from an appeal court opinion on a provincial reference. The Canadian Coalition for Genetic Fairness*, an intervener at the QCCA, has filed a notice of appeal. The appeal of the GNDA Reference will likely be heard by the SCC in the fall.

The main question posed in the appeal will be whether the GNDA addresses a real, public “harm.” Critics of the GNDA have expressed concern that the criminal law power might be illegitimately used to invade and usurp provincial jurisdiction. Indeed, the “scope of the federal power to create criminal legislation with respect to health matters is broad” (RJR MacDonald v Canada, [1995] 3 SCR 1999 [RJR-MacDonald]). However, it “is not unlimited” (Reference re: Firearms Act, 2000 SCC 31 [Firearms Reference]), and is restrained by the requirement of a valid criminal law purpose, directed at a legitimate public “evil” (Reference re: Validity of Section 5(a) Dairy Industry Act, [1949] SCR 1 [Margarine Reference]).

This case comment argues that the GNDA is a valid use of the federal criminal law power and that the Act‘s effects on matters within provincial jurisdiction, such as the formation of insurance contracts, are incidental. As the QCCA found, the Act‘s central purpose is to protect and promote health by addressing Canadians’ fears that the results of their genetic tests could be used against them. Contrary to the QCCA’s conclusion, this qualifies as a valid public health purpose. The GNDA therefore should be upheld at the SCC as a valid exercise of the federal criminal law power even thought it has significant incidental effects on provincial legislative matters.

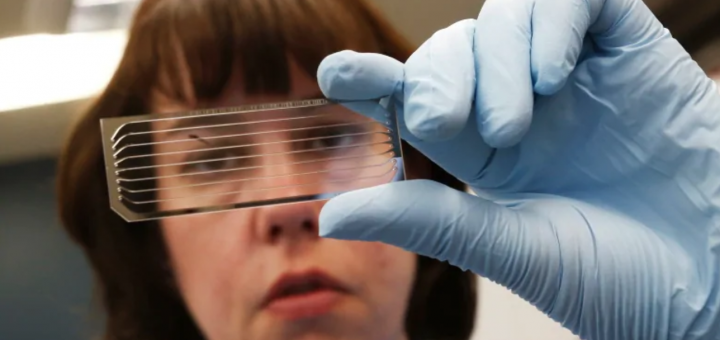

The Genetic Non-Discrimination Act

During the Parliamentary debate on the GNDA, Senator Cowan and leading experts in genetic medicine presented evidence that Canadians were choosing not to pursue beneficial and preventative genetic testing out of fear that the results of their tests could be used against them in unpredictable ways. Senator Cowan told Parliament that Canada was alone in the G7 to not have enacted legislation against genetic discrimination. He also reported that the most difficult testimony he heard regarding the necessity of such legislation came from the parents of sick children who faced devastating decisions, having been told by doctors that genetic testing may help better treat their children but that it may also preclude them in the future from accessing health insurance.

After the Act passed into law in 2017, the Privacy Commissioner of Canada and the Chief Commissioner of the Canadian Human Rights Commission welcomed the Act. The latter noted that “[t]aking a test that could help save your life shouldn’t have to be a calculated risk.” However associations speaking on behalf of the insurance industry objected, arguing against the constitutionality of the Act.

The Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association (“CLHIA”) argued in its factum that the discrimination at issue in the GNDA went beyond the criminal law jurisdiction of Parliament, not only because the regulation of insurance fell squarely within provincial jurisdiction but also because the GNDA‘s prohibitions against using the results of genetic testing did not address a legitimate harm to public health. The CLHIA, as well as intervenors against the GNDA including the Attorney Generals of Canada and British Columbia, argued that the evidence that Senator Cowan presented suggested only that concerns over genetic discrimination may affect health, but did not establish that they did in fact do so. Promoting beneficial health practices, the intervenors argued, was not a valid use of the criminal law power, and holding otherwise would upset the constitutional balance of power.

The QCCA Opinion

The QCCA took the view that the GNDA does not have a criminal law purpose. In doing so, it seems to have largely based its conclusion regarding the purpose of the Act on its effects. However, the fact that the GNDA has a significant impact on insurance contracts and employment is not enough to establish that the impugned provisions of the GNDA are in pith and substance in relation to provincial matters. Many valid criminal laws – for example, laws that have to do with food, drugs, and obscene materials – impact on property and contractual rights (Firearms Reference at para 50).

Interestingly, the QCCA seemed to have agreed that the Act‘s central purpose is to “protect and promote” health “by fostering the access by Canadians to genetic tests for medical purposes” (GNDA Reference, QCCA, at para 9). The QCCA opinion provides that the main purpose of the Act is “to prevent that Canadians refrain from undergoing genetic tests for medical purposes for fear that the results be used without their consent in the context of a contract or of a service” (GNDA Reference, QCCA, para 9). However, the court concluded that this does not constitute an “evil” within the meaning of criminal law. It reasoned that although the Act would make obtaining nonconsensual genetic information “more difficult” (GNDA Reference, QCCA, para 10), it does not completely ban insurance companies and other parties from accessing such information through the traditional means of other medical tests or family history. The court concluded that “higher quality health care through the promotion of access to genetic tests” cannot be a valid criminal law purpose (GNDA Reference, QCCA, at para 24).

What the Case Law Says About a Valid Criminal Law Purpose

The law establishes that legislation may be classified as valid criminal law if it fulfills three prerequisites: (1) a valid criminal law purpose backed by (2) a prohibition and (3) a penalty (Margarine Reference, Firearms Reference). In the Margarine Reference, Justice Rand ruled that a valid criminal legislative purpose was generally directed at an injurious public “evil,” such as a harm against “[p]ublic peace, order, security, health, [or] morality,” but that it need not be confined exclusively to those categories (Margarine Reference at page 50). Because the GNDA includes a prohibition and a penalty, the crucial question is whether the Act addresses a valid criminal public purpose in the sense contemplated by Justice Rand.

Although “health” is not a matter enumerated under the Constitution Act, 1867, the criminal law power has supported legislation pursuing health objectives in a range of contexts: the advertising of tobacco (RJR-MacDonald), the sale of drugs prepared under unsanitary conditions and false or misleading advertisement of drugs (R v Wetmore, [1983] 2 SCR 284), and the use and sale of marijuana as a personal and social harm (R v Malmo-Levine, 2003 SCC 74).

In RJR-MacDonald, the SCC ruled that the hazard of tobacco was a valid and injurious public health “evil” and that a concern for protecting Canadians from tobacco was a valid criminal law purpose. That decision was based on a “copious body of evidence” introduced at trial that demonstrated “convincingly” that “tobacco consumption is widespread in Canadian society and … poses serious risks to the health of a great number of Canadians” (RJR-MacDonald at para 30). In Malmo-Levine, the majority opinion of Justices Gonthier and Binnie held that despite gaps in our knowledge of the harms to health caused by marijuana, Parliament was still entitled to act on the basis of a “reasonable apprehension of harm” (RJR-MacDonald at para 41). RJR-MacDonald also noted that “it has long been recognized that there also exists a preventative branch of the criminal law power” (ibid).

GNDA: Provincial Regulation or Valid Criminal Purpose?

The main issue that the upcoming GNDA appeal presents is whether the effects of the Act on provincial jurisdiction are merely incidental, or whether regulating insurance lies at the core of the GNDA‘s purpose.

The QCCA’s opinion sided with opponents of the Act in finding that the Parliamentary debates’ heavy focus on the Act‘s effects on insurance companies provided evidence of its aim to regulate provincial matters. However, although the Parliamentary debates did devote significant time to considering the GNDA‘s effects on insurance companies, the debates were driven primarily by the concerns of medical doctors and researchers. These experts testified that they dealt with patients “every day” who were faced with difficult decisions about whether or not to undergo genetic testing because of a fear that the disclosure of such information to insurance companies may prevent them from accessing insurance. The evidence before Parliament showed that such concerns inhibited Canadians from undertaking genetic testing, even in cases where it could assist with the diagnosis and prevention of disease.

Parliament has the power to choose the legal means it considers most effective in suppressing a public “evil.” In RJR-MacDonald, the SCC held that a pith and substance analysis aims to determine Parliament’s underlying purpose in enacting a piece of legislation; it is not aimed at determining whether Parliament has chosen that purpose wisely or whether it would have achieved that purpose more effectively by legislating in other ways (RJR-MacDonald at para 44). The pith and substance equally does not involve a reassessment of the evidence or policy arguments considered in the legislative process, apart from ensuring that Parliament acted on the basis of a “reasonable apprehension of harm” (Malmo-Levine at para 78). In Malmo-Levine, in upholding the prohibitions on the use of marijuana as a valid exercise of the criminal law power, Justices Gonthier and Binnie held that “if there is a reasoned apprehension of harm, Parliament is entitled to act, and in our view Parliament is also entitled to act on reasoned apprehension of harm even if on some points ‘the jury is still out’” (Malmo-Levine at para 78). The justices also held that “[o]nly when the effects of the legislation so directly impinge on some other subject matter as to reflect some alternative or ulterior purpose do the effects themselves take on analytic significance” (RJR-MacDonald at para 44).

A study of the legislative record as a whole reveals that Parliament’s main intention was to promote health, not to regulate the insurance industry, through the GNDA. The Act‘s prohibitions are directed to “any person;” they do not target insurance companies. The GNDA also does not significantly hinder the ability of the provinces to regulate insurance services or employment law. The double aspect doctrine permits Parliament and provincial legislatures to pass laws dealing with genetic discrimination within their respective jurisdictional fields for different purposes.

Parliament concluded that the GNDA addresses gaps in the law. One example discussed in Parliament was that, without the GNDA, a Canadian resident of Nova Scotia (for example) may submit to genetic testing in his or her home province under the understanding that the results of that test are secure, only to move to another province which has no such protections, potentially leading to a nonconsensual disclosure. Parliament considered that the prohibitions of the GNDA would be the best way to provide patients with confidence that their test results were secure and enacted the legislation.

In undertaking the pith and substance analysis, the Supreme Court will also need take into account that all legislation passed by Parliament or a provincial legislature is entitled to a presumption of constitutionality. The party alleging unconstitutionality has the burden of demonstrating that legislation adopted through a democratic process is invalid. According to Peter Hogg, “in choosing between competing, plausible characterizations of a law, the court should normally choose that one that would support the validity of the law;; furthermore, the court’s role is to determine whether the legislature had a “rational basis” for legislating as it did, and acted on the basis of a “reasonable apprehension of harm.”

Conclusion

As the GNDA attempts to update the law to the twenty-first century’s advanced, accessible, and pervasive genetic technology, it poses questions of whether regulating the uses of genetic tests may be a valid subject of criminal sanction. (It may also raise questions of whether data protection in other privacy-related areas – data theft, unsolicited sexting, etc – could also be valid criminal law purposes in the twenty-first century.) Parliament received convincing expert evidence that Canadians hold real concerns about a lack of strong, clear legal protections against genetic discrimination, and that these concerns have inhibited patients from undergoing genetic testing, with negative consequences for their health.

In light of the broad and flexible approach the SCC has taken to Parliament’s criminal law power, there is a good chance the QCCA opinion will not survive on appeal. The SCC has been careful “not to freeze the definition in time or confine [the criminal law power] to a fixed domain of activity” and has emphasized that it has “always defined [the] scope [of s.91(27)] broadly” (RJR-MacDonald at para 28). Finally, that provinces remain free to address the civil consequences of genetic discrimination should alleviate concerns about the GNDA upsetting the balance of the division of powers.

*The author provided research assistance to counsel for the Canadian Coalition for Genetic Fairness in the preparation of the Coalition’s submissions to the QCCA.

Join the conversation