R. v. Hills: SCC Overturns Harper-Era Mandatory Minimum Sentence (Part II)

The Supreme Court of Canada [“SCC” or “The Court”] recently released its decision on three Alberta cases: R. v. Hills 2023 SCC 2 [“Hills”] and R. v. Hilbach 2023 SCC 3 [“Hilbach”], the latter argued with the companion appeal, R. v. Zwozdesky. These cases challenge the constitutionality of mandatory minimum sentencing provisions, inviting the Court to clarify the interpretation of s. 12 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms [“Charter”]. Section 12 guarantees the right not to be subjected to cruel and unusual treatment or punishment.

The SCC held that s. 244.2(3)(b) of the Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c C-46 [“the Code”], requiring a four-year minimum sentence for an aggravated form of the offence of intentionally discharging a firearm, violated s. 12 of the Charter. Parliament has since passed an amendment which removes mandatory minimum sentences for several drug- and firearm-related offences, including the one at issue in this case.

This post is the second of a two-part series on Hills. In this installment, I focus on the Court’s treatment of mandatory minimum sentencing regimes. In the first, I discussed the use of reasonable hypothetical scenarios to challenge the constitutionality of Charter provisions.

Background Context

During the week of March 21, 2022, the SCC heard four appeals on the issue of proportionate sentencing, all challenging the constitutionality of sentencing provisions made by the Conservative government of former prime minister, Stephen Harper. Hills and Hilbach are the last of the decisions on these cases to be released. In R. v. Bissonnette 2022 SCC 23, the Court struck down a provision allowing sentencing an offender to life imprisonment without a realistic possibility of parole, while in R. v. Sharma 2022 SCC 39 [“Sharma”], a slim majority upheld the constitutionality of provisions that restricted the availability of a conditional sentence for an Indigenous offender.

Sharma and Hilbach are exceptions in an increasingly long list of cases in which the SCC struck down Harper-era amendments to the Code. Late last year, in R. v. Ndhlovu 2022 SCC 38, the Court held that provisions mandating the registration of sex offenders in a national registry were unconstitutional. In 2018 and 2016, the SCC also struck down provisions requiring a victim surcharge and a mandatory minimum sentence for drug trafficking (in R. v. Boudreault 2018 SCC 58 and in R. v. Lloyd 2016 SCC 13, respectively).

The Facts

Mr. Hills consumed a large amount of prescription drugs and alcohol, before leaving his home in Alberta with a loaded big game hunting rifle and a baseball bat (for details of the facts, see Hills, paras 16-20). The driver of a passing car called the police after Mr. Hills swung his bat at the car and fired a shot at it. Before the police arrived, Mr. Hills had smashed the windows of a parked car and fired his gun at a residential home. The shots were fired into parts of the home where a person could have been hit.

Mr. Hills could not recall any of these events and did not know why he had acted as he did.

Judicial History

Mr. Hills pled guilty to four offences related to causing property damage, pointing and discharging a firearm, and possession of a firearm without a licence (for details of the judgments below, see Hills, paras 21-28). At sentencing, Mr. Hills challenged the constitutionality of s. 244.2(3)(b) of the Code, which imposes a four-year mandatory minimum sentence for intentionally discharging a non-restricted firearm into or at a house. To do so, Mr. Hills employed a reasonable hypothetical scenario to illustrate that the minimum sentence was grossly disproportionate and therefore, violated s. 12 of the Charter.

Because the wording of the provision captures circumstances of low moral blameworthiness and risk of harm as described in the hypothetical scenario, the sentencing judge concluded that the impugned provision was unconstitutional. The judge imposed a lesser sentence of three and a half years of imprisonment for Mr. Hills.

The Crown appealed, and the Alberta Court of Appeal (“ABCA”) allowed the appeal on both the finding that the impugned provision violated s. 12 and the sentence imposed. Justice Antonio held that four and a half years of imprisonment was an appropriate sentence for Mr. Hills. In their concurring opinions, Justices O’Ferrall and Wakeling called for the SCC to revisit its s. 12 jurisprudence. They criticized prevailing sentencing principles in Canada, going so far as to say that sometimes a grossly disproportionate sentence could be justified (Hills, para 27).

The SCC Decision

The Court reaffirmed that s. 12 is engaged whenever state action amounts to punishment and that imprisonment is the “penal sanction of last resort” (Hills, para 31). Proportionality is a central tenet of Canada’s sentencing regime, and courts should fix sentences in light of the principles of parity and proportionality (Hills, paras 56 and 145).

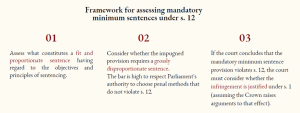

Writing for the majority, Justice Martin began with a detailed clarification of the framework for challenging a mandatory minimum sentence under s. 12. Section 12 protects against grossly disproportionate punishment due to their particular effects, as well as punishment that is inherently cruel and unusual. Mandatory minimum sentencing provisions fall into the first category, as it is the absence of discretion and method of operation that make such provisions potentially unconstitutional (Hills, paras 35-38).

The first stage of the analysis to evaluate mandatory minimum sentences under s. 12 poses the question: what specifically is the fit sentence for either the actual offender or a reasonably foreseeable offender in a reasonable hypothetical? (Hills, para 64).

Once the fit sentence is determined in the first stage, the second stage of the analysis poses the question: is the difference between the fit sentence and the mandatory minimum so grossly disproportionate that it amounts to cruel and unusual punishment? (Hills, para 47). The three-part inquiry at this stage evaluates:

- the scope and reach of the offence,

- the effects of the penalty on the offender, and

- the penalty, including the balance struck by its sentencing objectives such as denunciation, deterrence, and rehabilitation (Hills, para 122).

If a court finds a rights violation and the Crown raises arguments under s. 1 of the Charter to justify the breach, the court is required to proceed with a s. 1 analysis.

Applying the s. 12 framework to the facts in this hypothetical, the SCC held that, the sentencing judge’s analysis that a fit sentence in the hypothetical case would be up to 12 months’ probation. The mandatory sentence of four years in prison was held to be significantly out of sync with the appropriate sentence, and as such, violated s. 12. Since the Crown did not advance arguments that the punishment is justified under s. 1 of the Charter, the Court did not consider this issue.

The Court reinstated the sentencing judge’s lesser sentence for Mr. Hills. The provision was immediately declared of no force or effect, with the declaration applying retroactively.

The Dissent

The lone dissenting judge, Justice Côté, disagreed with the three-part approach to stage two of the test. She stated that each of the considerations set out by the majority for stage two are also relevant at stage one, when courts determine a fit and proportionate sentence. As such, the clarification at this stage would only duplicate the analysis relevant to determining the low end of the range of fit and proportionate sentences. It does not, however, provide any additional guidance to courts; “whether a minimum sentence is grossly disproportionate to the fit sentence … remains a normative judgment” (Hills, para 182).

Justice Côté also disagreed that the impugned provision captures the conduct contemplated in the hypothetical advanced by Mr. Hills, and as such, would have dismissed Mr. Hills’ appeal.

Commentary

The use of mandatory minimum sentencing has been the subject of long-standing debate. Defenders of mandatory minimums argue that they achieve uniformity in sentencing and promote the rule of law by removing the unpredictability of courts exercising discretionary powers. Critics, on the other hand, argue that they fly in the face of a significant body of evidence showing that mandatory minimums inflate sentences for all offenders, fail to act as an effective deterrent, and are disproportionately imposed on offenders from marginalized populations.

The decision in this case must be read in context with the recent surge in cases heard by the Court, challenging mandatory minimums. The jurisprudence so far indicates that the Court is doing its best to toe the middle ground between proponents and critics of mandatory minimum sentences. It is careful to retain deference to parliament’s authority to legislate on punishment. But at the same time, the Court has criticized mandatory minimum sentencing as “blunt instruments … which may impose unjust sentences” (R v Nur 2015 SCC 15, para 44), showing its willingness to strike down sentencing provisions that skew too far away from the principle of proportionality.

However, for all its well-intended efforts to establish a robust framework providing guidance for courts, Justice Côté is right to point out that the comparative exercise of determining whether a sentence is grossly disproportionate to the fit sentence remains a normative one (Hills, para 183). Courts necessarily must consider the three factors in the second stage of the test, when it determines the fit sentence in the first stage. If the appropriate sentence misses the mark in comparison to the actual sentence, the clarificatory value of duplicating the same analysis in the second stage is limited. Courts will still have to make a judgment call on whether the discrepancy is minor enough to be entitled to deference, or whether it is serious enough to constitute a violation of the Charter. As the dissent notes, there is no magic to qualitative, normative phrases like “so excessive as to outrage standards of decency”; they simply serve as useful language for courts to signal that, despite the high bar that courts must meet before they can interfere with Parliament’s authority to choose penal methods, the provision still falls short of constitutional requirements.

The question of to what extent judges should rely on moral reasoning in deciding the cases before them, is itself a normative question. Are judges well-positioned to address ethical issues that are engaged in Charter rights? Whether or not they have superior moral reasoning skills, should courts engaging in moral analyses concern us in some cases? Do we, as society, want judges to actively participate in deliberations of this sort on our behalf? Should this be the sole preserve of the legislature? No doubt, these are important philosophical questions. But it is clear that at least in cases where the established legal test only provides qualitative guidance, courts will have to make some normative deliberations to arrive at a decision. In this case, the majority was satisfied that on balance, the relevant factors weighed in favour of overturning the legislature’s reasoning, while the dissent did not.

It is also important to notice that when Parliament decides to remove judicial discretion in sentencing, discretionary decision-making is not removed entirely from the process; rather it is transferred to prosecutors. For instance, in the case of hybrid offences with mandatory minimum sentences, prosecutors can choose to proceed by indictment, thereby compelling courts to impose the mandatory minimum. Moreover, making a successful abuse of process challenge against a prosecutorial decision is a difficult task, since in all but the most egregious cases, courts cannot monitor discretionary decisions made by the prosecution without risking their function as impartial arbiters. So where there is prosecutorial discretion, it is exercised largely free from judicial review.

Ultimately, exercising discretion is an inescapable aspect of crafting an appropriate sentence that fits the crime and the circumstances of the offender. The prevailing balance struck between the judiciary and the legislature in making and interpreting the law is perhaps an uneasy one. But those who are concerned about the broad grant of discretionary powers to unelected judges may not find much solace in removing judicial discretion, only to end up with an expansion of discretionary powers to prosecutors.

Join the conversation