The Structal Case: Are the practical realities of the construction industry being sacrificed for legal formalism?

Stuart Olson Dominion Construction Ltd. v Structal Heavy Steel, 2015 SCC 43 [Structal] is the most recent case by the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) on the correct interpretation and application of the trust provisions found in provincial construction lien statutes. The issue before the SCC was whether a contractor’s statutory obligation to hold a sub-contractor’s monies in trust was properly discharged by posting a lien bond guaranteeing payment of the entire amount to the sub-contractor.

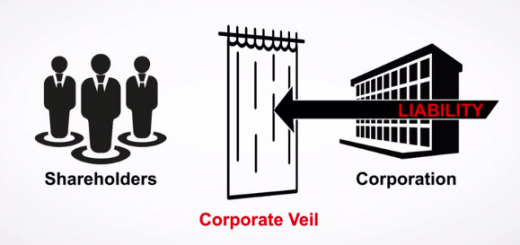

The Manitoba Builders’ Lien Act, CCSM c. B91 [BLA], like the Ontario Construction Lien Act, RSO 1990, c. C.30 [CLA], gives building contractors a right to register a lien against an owner’s property where no privity of contract exists with the owner. In addition, owners and contractors who hire other tradespersons, are required to hold monies in trust for subcontractors below in the pyramid, rather than apply this money to satisfy other obligations. A contractor faced with a lien can dispute the claimed amount by paying monies into court to discharge the lien, or by posting a bond for the entire amount claimed. The contractor may then proceed to defend the claim or counter sue. This situation raises the question of whether posting a bond discharges these trust obligations and hence frees up the contractor’s funds.

In interpreting the language of the Manitoba statute, the SCC ultimately found the trust and lien provisions under the BLA to be separate and distinct remedies, simultaneously available to claimants. It held that the undisputed portion of the funds owing were subject to a trust despite the contractor having posted a lien bond for the entire amount. The SCC recognized that paying the entire amount of the lien into court would have discharged the trust, but failed to articulate a requirement to distinguish between disputed and undisputed funds being held in trust in the context of a lien bond. While the SCC’s decision, given the facts of this case, appears sensible, the analysis leads to a potential conclusion that all funds claimed under a lien action must be set aside if a lien bond is relied upon to discharge the lien. This holding fails to account for the practical realities of the construction industry, namely the prevalent use of bonding to preserve liquidity and cash flow in a project.

Facts

Dominion Construction Company Ltd. (“Dominion”) was hired by BBB Stadium Inc. (“BBB”) the developer and owner of the project lands, as general contractor to build a new stadium at the University of Manitoba. Dominion in turn hired Structal as sub-contractor to supply and install the steel structure for the stadium at a cost of $44,435,383. As the work progressed, Dominion withheld payment on Structal’s monthly billings for back charges resulting from Structal’s alleged delays. Structal registered a builder’s lien against the property owned by BBB permitted under s. 13 of the BLA for $15,570,974.43 of which $8,067,558.59 was for its own delay claim and the balance for unpaid invoices and statutory hold-back.

Dominion subsequently filed a lien bond permitted under s. 55(2) of the BLA which provided for payment of the entire amount of any lien judgment made against Dominion that it failed to satisfy, including costs. Dominion failed to make further payments to Structal, claiming it had a set-off against the $8 Million claimed by Structal, effectively taking the position that it had already posted security not only for the improvements made but for the disputed delay claim. Thus, it refused to hold the monies owed to Structal, for work performed subsequent to the dispute, in trust for Structal as required by ss. 4-9 of the BLA, because it felt it had already secured these amounts by the lien bond which provided for the entire amount of any lien judgment made against Dominion. It disputed liability for payment of the subsequent work, through set-off, on the basis the lien bond would pay if Dominion were found liable for this amount.

Unfortunately Structal disagreed with this position. They demanded that $3,538,029.97, the value of the subsequent work, be withheld by the BBB, the developer and owner of the project lands, otherwise it would bring an action against BBB for violating its trust obligations under the BLA. After the owner withheld the funds, which Dominion required to pay other contractors, Dominion applied to the Court of Queen’s Bench (“CQB”) for a declaration it had satisfied its trust obligations by posting the bond. The CBQ held that the lien bond posted for Structal’s $8,067,558.59 delay claim was adequate security to “extinguish” Dominion’s trust obligations for the $3,538,029.97 even though Structal had already paid its sub-contractors more than this amount. In doing so, the applications judge treated all amounts claimed by Structal as falling under the disputed funds secured by the lien and did not treat the monies owed for the subsequent work as separate. However, this amount had been certified for payment and Dominion’s only basis for not paying was a claimed set-off. The applications judge held that requiring Dominion to hold these funds in trust when they were covered by the lien bond amounted to double payment and was commercially unreasonable.

The Manitoba Court of Appeal disagreed and took to interpreting the statute. It held that the right to file a builders’ lien and the trust claim were two separate and distinct remedies that could be pursued independently. Dominion appealed the decision. The SCC undertook a more formalistic exercise of interpreting the meaning of each provision and whether the BLA contemplates their interaction. It upheld the Court of Appeal’s decision and elaborated on the correct application of each provision.

What the SCC overlooked and future decisions

Ultimately, the SCC came to a sensible decision in the circumstances, but did so for the wrong reasons and created the potential for commercially unreasonable outcomes in future decisions.

The SCC focused its analysis on the historic and functional differences between the lien and trust remedies, citing that the trust provisions were far reaching and operate as a distinct remedy that can be pursued concurrently with a lien claim. Its basis was that: 1) trust provisions function to ensure that monies owing to contractors in the construction pyramid are not improperly diverted, 2) that finding a trust claim is extinguished by a lien bond would undermine this purpose, and 3) a lien bond provides no more security than a lien because the lien claimant must be successful in the action to collect.

An important factor not given adequate attention is that the lien bond purportedly guaranteed the maximum amount of any judgment against Dominion in Structal’s lien action. If true, this would make the lien bond a superior form of security. Thus, if Dominion’s claimed set-off against the subsequent (undisputed) work failed at trial, the lien bond would presumably pay.

Or would it? If in addition, Dominion is found to be owing the $8,067,558.59 and its set-off fails, it is unclear, from the facts, that the lien bond would cover the $3,538,029.97. Moreover, the trial judge overlooked the factual reality that this latter amount is for separate undisputed work, incurred after Structal’s lien was registered for the initial work. Dominion took the opportunity to stop payment for future work by claiming a set-off against the security it had in Court for the disputed amount. It did this even though the lien bond’s coverage of the subsequent (undisputed) amount was unclear. Had it been found liable for the entire $15,570,974.43, the coverage of the lien bond may have been limited to only that amount and would not have extended to the subsequent claim. While it was entitled to dispute Structal’s lien claim and even counterclaim against it, it was not entitled to help itself to the $3,538,029.97 of undisputed funds in advance of the lien claim against it being determined. Yet it helped itself to this collateral amount outside of the lien dispute’s purview. Structal was correct in bringing a breach of trust action for this amount.

However, this was not the basis for neither the Court of Appeal’s nor the SCC’s decision. The SCC took a formalistic analysis of the separate and distinct nature of the lien and trust remedies, when the substantive question was whether the subsequent claim fell under the security posted for the previous claim. This was a question of fact.

Interestingly the SCC recognized that paying the entire amount of the lien into court would have discharged the trust, but maintained that a lien bond could not do the same. It was unclear whether the Court meant that Dominion could have discharged the trust by putting up funds for the original $15,570,974.43 plus the $3,538,029.97 or without. In any event, the SCC failed to articulate a requirement to distinguish between disputed and undisputed funds being held in trust in the context of a lien bond. The resulting precedent is that a lien bond cannot be used to discharge trust obligations even if the entire amount is disputed by the general contractor and this form of security is posted.

The effect of this decision is not double payment at the general contractor’s expense, as the trial judge suggested, but a tying up of Dominion’s operating capital. In other words, Dominion would be required to put money up to secure the lien claim and then again to secure the trust claim for the same disputed amount because these are two separate remedies.

Lien bonds are very commonly used in the construction industry, as developers and general contractors are highly leveraged. Bonds in general are hard to obtain and are dependent on the contractor’s liquidity, credit and the strength of the project. While speculation, it can be plausibly inferred from the facts that the relationship between Dominion and Structal was coming to an end and that perhaps Dominion needed these funds to hire a new steel contractor.

Conclusion

The precedent set by this decision would potentially have the effect of requiring contractors to post security twice for the same claim, constraining their cash flow and jeopardizing their ability to complete projects. Clearly, this is not what the Court intended, yet it failed to approach the matter substantively and took a formalistic approach to interpreting the BLA instead. This is troublesome because the construction lien statutes of most provinces, including Ontario, are almost identical to that of Manitoba. How provincial courts will apply this decision remains to be seen.

Join the conversation