The Supreme Court in Statistics

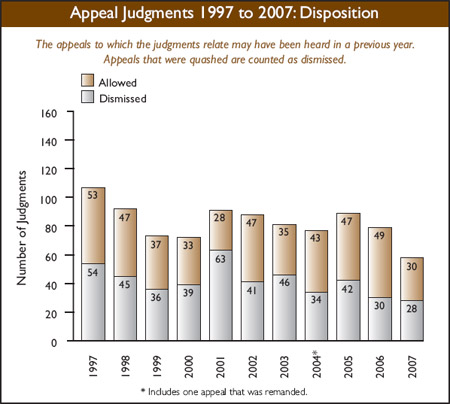

In his annual review of the Supreme Court, excerpts of which were featured in both the Toronto Star and The Globe and Mail, Dean Patrick Monahan pointed to the existence of a number of interesting trends in the character, content and volume of the jurisprudence of Canada’s top court. Among other things, Dean Monahan presented the Supreme Court’s 58 judgments in 2007 — the lowest total since 1975 — as evidence of the existence of a five judge bloc (composed of Chief Justice McLachlin, the now retired Justice Bastarache, and Deschamps, Charon, and Rothstein JJ.) notable for their pragmatic, cost-conscious approach to judicial decisionmaking.

A look at the statistics page on the Supreme Court of Canada’s website indeed reveals a number of interesting trends in Supreme Court jurisprudence. What follows is an unscientific analysis of some of the statistics posted on the Supreme Court’s website. All images are courtesy of the Supreme Court of Canada’s website.

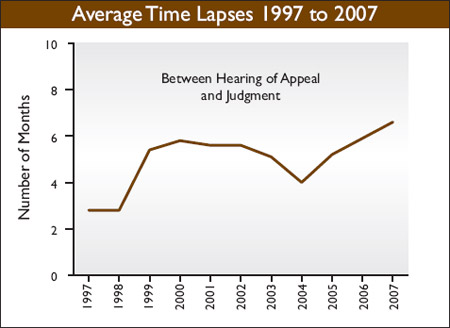

Pensive or Lethargic? The Growing Time Lag Between Hearings and Judgments

Despite its decreased caseload, the Supreme Court is taking a longer time to release decisions. On average, it now takes the court in excess of six months to render judgment in a case once it has been heard. This figure is up almost 2 months from 2004.

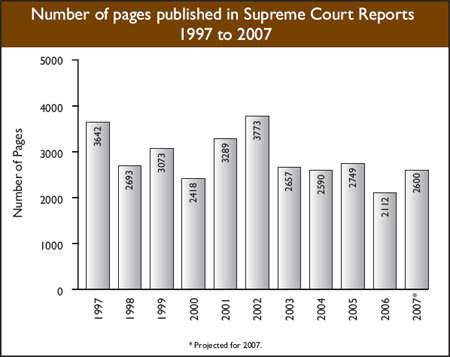

This increase in the duration of time between hearings and judgments may be evidence of a tactical shift in judicial decision-making. The extra two months the court now takes to release its decisions surely allows it to bring a closer, more thoughtful analysis to bear on each case. Perhaps this explains why the steady decline in Supreme Court decisions over the past few years has been accompanied by a far less pronounced decline in the number of pages published per year in Supreme Court Reports (with the anomalous exception of 2006). What this suggests is that the Supreme Court is writing more pages per decision. Although it would be foolhardy to suggest a direct correlation between number of pages per decision and ‘thoughtfulness,’ perhaps an increased pages per judgment ratio does — on a very broad level — suggests that a greater amount of attention is being awarded to each decision. Indeed, many of these pages are likely devoted to dissenting and concurring opinions, both of which, as will be considered in the next section, have also increased in recent years.

However, there are considerable drawbacks associated with having a six month gap between hearings and judgment — even if the court’s lack of haste is a function of greater prudence. Chief among these is the adverse effect that increased delay can have on access to justice. The manner in which access to justice is implicated is fairly intuitive: litigants seeking out the court of last resort to vindicate rights which are being violated have to wait longer to have those rights vindicated. That said, both the costs and legal resources associated with seeking leave to appeal to the Supreme Court already make it a prohibitively selective venue for the vindication of rights.

Moreover, in the context of an increasingly fast paced legal environment, a court which takes almost two years from the date of filing to the release of decision does not seem particularly well positioned to respond fast enough to the wealth of emerging legal issues. That said, the Supreme Court has demonstrated its ability to act with haste when the situation requires. The best example is the court’s latest decision, (released with reasons to follow), BCE Inc., et al. v. A Group of 1976 Debentureholders, et al. Que.) (Civil) (By Leave) (32647) (see here for the procedural history of the case).

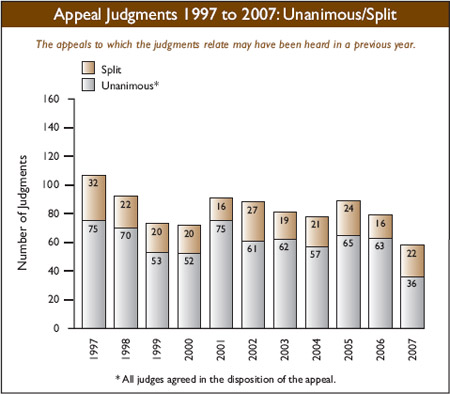

A Divided Court

As Dean Monahan pointed out, the Supreme Court is more divided than ever before. Twenty-two of the court’s fifty-eight decisions in 2007 were not unanimous. This is easily the highest ratio of split to unanimous decisions in the last ten years.

Dean Monahan attributes this increased division in the Supreme Court to a “slight rebalancing” in the court, toward a “somewhat more cautious approach on some Charter issues.” (See here for a news release detailing more of Dean Monahan’s findings).

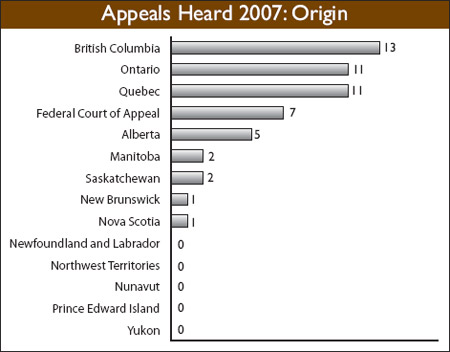

The Curious Dominance of British Columbia in the Supreme Court

This one is truly an enigma. B.C. is disproportionately well represented in the Supreme Court. The top court fielded thirteen appeals from the province; two ahead of both Ontario and Quebec, both of which are considerably more populous than British Columbia.

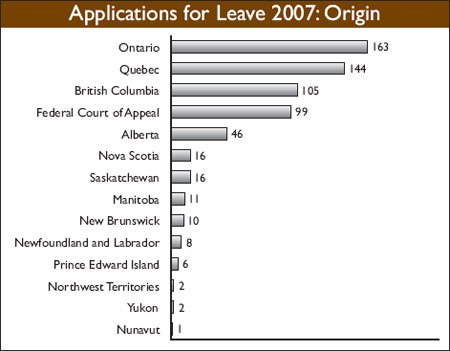

B.C.’s dominance cannot be explained away by an overly litigious bar. The province ranked a distant third (consistent with its population) in applications filed for leave to the Supreme Court.

Also striking is the paucity of representation in the Supreme Court of the Maritime provinces. In 2007, the Supreme Court heard a mere two cases, (one from New Brunswick and the other from Nova Scotia). To be fair, however, this figure is broadly commensurate with the substantially fewer applications for leave to appeal to the Supreme Court that originated in Maritime provinces.

Final Thoughts

It bears repeating here (although it should be rather self-evident) that the foregoing is not a measured empirical analysis but is instead a modest interpretation of SCC stats. The portrait that emerges is of a Supreme Court, either pensive or lethargic but definitely divided, with a puzzling predilection for the province of British Columbia.

Join the conversation