Free Pass Faux Pas: The Charter Still Applies to Extraterritorial Activities

Introduction

In R v McGregor, 2023 SCC 4 [McGregor], the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) dismissed an appeal from the Court Martial Appeal Court of Canada. This case involves the consideration of the extraterritorial application of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11, s 91(24) [Charter] and the framework of the territorial reach of the Charter—R v Hape, 2007 SCC 26 [Hape].

Facts

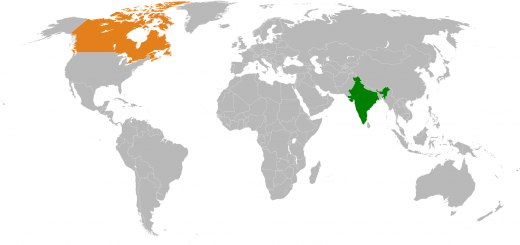

Corporal Colin McGregor (“M”), the appellant, held diplomatic status as a member of the Canadian Armed Forces (“CAF”) posted to the Canadian Defence Liaison Staff at the Canadian Embassy in Washington, DC, between August 2015 and March 2017. M resided in Alexandria, Virginia, when he worked as a resource-management support clerk in Washington.

In 2017, another CAF member posted in Washington found two audio recording devices in her residence. She became suspicious of M and believed M held responsibility for placing the devices in her home. After an investigation, the Canadian Forces National Investigation Service (“CFNIS”) reasonably suspected M of voyeurism and possessing a surreptitious private communications interception device.

Since M’s residence was not on CAF property, the CFNIS could not issue a search warrant pursuant to section 273.3 of the National Defence Act, RSC 1985, c N-5. Instead, the CFNIS and the Alexandria police cooperated in obtaining a search warrant under Virginia law. The Canadian Embassy waived M’s diplomatic immunity vis-à-vis his property and residence. The Alexandria police, after a search on February 16, 2017, discovered certain audio recording devices (McGregor, para 7).

Through a criminal investigation, forensic investigators analyzed the devices and discovered incriminating evidence pertaining to a sexual assault. A CFNIS investigator arrested M in Washington, and M brought a motion in the Court Martial, submitting that the search and seizure operation contravened section 8 of the Charter. M also sought to exclude the evidence discovered from the process pursuant to section 24(2) of the Charter (i.e. the provision governing the exclusion of evidence in the face of Charter violations).

The military judge, the Court Martial Appeal Court, and the SCC determined that the search and seizure operation did not contravene the Charter. The SCC dismissed M’s appeal and upheld M’s convictions of voyeurism, possession of a device for surreptitious interception of private communications, sexual assault, and disgraceful conduct.

M argues that, according to Hape, the Charter prevents the CFNIS from searching and seizing his electronic devices. The Crown takes the opposite stance: Hape allows the search and seizure.

Analysis

- Majority

Côté J first turned to the extraterritorial application of the Charter. She penned that this is not an appropriate case to reconsider this issue as the parties’ main contention does not involve extraterritoriality. Instead, the appellant and the respondent solely debate how the Hape framework applies to the facts. Referring to Sopinka J’s comments in Phillips v Nova Scotia (Commission of Inquiry into the Westray Mine Tragedy), [1995] 2 SCR 97, Côté J explained that the SCC “should not decide issues of law that are not necessary to a resolution of an appeal” (para 6). Thus, the Charter does not apply in this case.

Côté J argued that even if the Charter did apply to the CFNIS’ actions, M’s appeal would still not succeed. In this case, the CFNIS investigators acted reasonably, and the search and seizure operated according to legal authorization.

Section 8 of the Charter specifically grants “the right to be secure against unreasonable search or seizure.” The criteria of reasonableness are satisfied when the search “is authorized by law,” “if the law itself is reasonable and if the manner in which the search was carried out is reasonable” (R v Collins, [1987] 1 SCR 265, p 278; Wakeling v United States of America, 2014 SCC 72, para 41). In light of technological innovations and the privacy interests involved in “personal computer data” (R v Reeves, 2018 SCC 56, para 35), reasonableness is satisfied via the existence of a “specific, prior authorization” (R v Vu, 2013 SCC 60, para 3). A specific, prior authorization involves the police satisfying “the authorizing justice that they have reasonable grounds to believe that any computers they discover will contain the things they are looking for” (R v Vu, 2013 SCC 60, para 3).

In this case, the CFNIS obtained proper authorization from the Alexandria Police Department and the Canadian Embassy (indeed, perhaps the only available legal mechanism) to search a CAF member’s private residence outside Canadian law’s reach. The incriminating evidence subsequently unearthed neither invalidates the legitimacy of the prior search nor contravenes section 8 of the Charter.

- Concurring

Although Karakatsanis and Martin JJ agreed in dismissing M’s appeal, they ventured further to discuss the extraterritoriality of the Charter. They opined that a purposive reading of section 32 of the Charter demonstrates that the Charter covers the CFNIS investigators in a foreign state. Section 32 does not distinguish between the actions of state actors in Canada or abroad. Thus, the absence of geographical boundaries intentionally avoided limiting the Charter’s application (McGregor, para 53).

Conclusion

This case involves a further dimension of the integrity of the Canadian military. Integrity is an integral ethos of the Canadian military. Section of the Canadian Military Values stipulates that integrity calls for honesty, the avoidance of deception and adherence to high ethical standards. M’s convictions of disgraceful conduct and sexual assault constitute breaches of personal discipline—a vital value of the military. These breaches have the pressing potential to degrade military morale. These convictions do not reflect integrity as placing audio recording devices in a fellow officer’s residence represents serious infringements of another’s expectation of privacy and trust.

Even if these actions occurred outside Canadian soil, they are not immune from prosecution. Christine Van Geyn, the Litigation Director of the Canadian Constitution Foundation, underscores that special immunity for certain actors diminishes the rights and freedoms afforded to all Canadians. Canadian territory or not should be a sufficient condition of a free pass precluding criminal liability of state actors abroad.

Join the conversation