“More Than Mere Trimming”: Hockey, Judicial Arrogance, and Igloo Vikski

“Twas the saying of an ancient sage that humour was the only test of gravity, and gravity of humour. For a subject which would not bear raillery was suspicious; and a jest which would not bear a serious examination was certainly false wit.” – Anthony Cooper

“Humour [in the courtroom] must always be moderate, measured and appropriate to the occasion. But beyond this, humour needs no further justification. It is a legitimate expression of humanity and individuality. These are judicial virtues in the eyes of all except those who want courts to be staffed by robots preferably made in their own image.” – Justice Keith Mason

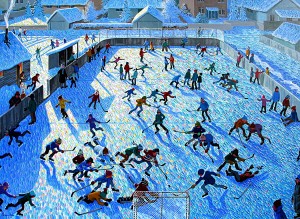

On the night of September 29, 2016, many Canadians from around the country began their familiar procession – from the general hustle and bustle of the outside world to a comfortable refuge in front of their TV – in order to watch Team Canada take on Team Europe in Game Two of the World Cup of Hockey. Fresh on the minds of those watching Team Canada claim the World Cup in a 2-1 victory, was, undoubtedly, the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) in Canada (AG) v. Igloo Vikski Inc., 2016 SCC 38 from earlier in the day, and the “final score” there of 8-1. As Sidney Crosby paraded Canada’s newest trophy around the ice, many fans were still lost in the deliberations of Justice Brown, who opened Igloo, for the majority, with an intrinsically Canadian flourish:

In wintertime ice hockey is the delight of everyone. Across the country, countless players of all ages take to ice rinks and frozen ponds daily to shoot pucks at the net. Often the puck is stopped or turned aside by a goaltender blocking it with a blocker or catching it with a catcher. This is notoriously difficult business. The goaltender’s attention must remain fixed on the play, and not on off-ice matters. His or her focus must not drift to thoughts of the crowd, missed shots or taunts from opponents. And, certainly, the goaltender should strain to avoid being distracted by the question before the Court in this appeal – being whether, for customs tariff classification purposes, he or she blocks and catches the puck with a ‘glove, mitten or mitt’, or with an ‘article of plastics’ (para 1).

First Period: Criticism

Astonishingly, highly respected legal scholar Alice Woolley has rebuked Justice Brown for his creativity in this opening paragraph, describing it as “judicial arrogance” that, while not “directly linked to injustice,” is still troubling because it “suggests the more systemic problem of a culture where conduct that looks like arrogance is permitted, and even celebrated.” With all due respect, I believe this is a sensationalized misreading of Justice Brown’s decision. While I agree that our legal system, and many of its decisions, could use a slice of humble pie, Justice Brown’s decision is not one of them. In fact, I would argue that it is the exact opposite of “judicial arrogance.” Amidst the highly exciting and intellectually compelling world of the minutiae of customs classification law, Justice Brown offered a decision that was wonderfully Canadian: a comment on how distanced the law can be, at times, from our lived realities, and the damage that stems from the hubris of those who believe this distance is somehow acceptable; all cast in the context of a game that is incredibly close to our Canadian hearts. This is not inside baseball (or inside hockey I should say): I have shared the judgment with several of my family members and friends who have no background in the legal field, and even without understanding Justice Brown’s reference to Denning, they still found the decision funny, and in fact, more relatable. They could immediately touch on the growing disenchantment between the law and our day-to-day lives. Additionally, one wonders what type of judgments from the SCC Woolley envisions if even Justice Brown’s opening paragraph rises to the dangerous level of “[looking] like arrogance” and “[turning] a decision about the rights and interests of parties before the court into an opportunity to show off the cleverness and erudition of the judge.” I recently learned that Leonid Sirota is of a similar opinion to my own when it comes to classifying Brown’s decision as “judicial arrogance,” arguing (in far more elegant terms than I have) that:

[Justice Brown’s decision] is not an example of arrogance at all; perhaps even the contrary. Professor Woolley takes Justice Brown to task for the opening paragraph of his opinion (for eight of the Supreme Court’s judges) [in Igloo], which begins with an allusion to Lord Denning’s famous “cricket case” dissent (Miller v Jackson, [1977] 1 QB 966), proceeds to quote from Ken Dryden’s The Game, and closes with a barely concealed recognition of the abstruse and slightly silly nature of the question at issue….if humour or lightheartedness can be an ingredient in the recipe of accessibility, so much the better…judges [do not have] to be stone-faced giants impervious to the feelings, including amusement, that the affairs of men and women might generate in others….Professor Woolley is probably demanding a level of self-abnegation that would not be realistic even if it were useful.

Let me be as clear as the ice on a freshly-shovelled skating rink: “arrogance” is a highly pejorative, subjective term. How does one begin to come to some sort of consensus around what defines judicial “arrogance”? Indeed, as both Sirota and Woolley point out, we are supposed to find this consensus somewhere near those moments where “injustice” starts to occur. But even then, if our judges are being unjust, is “arrogance” really the right term or point of focus?

Second Period: Arrogance or Humour or Somewhere In-between

Professor Woolley is not the first to raise concern over the “arrogance” of the judiciary and how it affects the solemnity of a legal opinion. Renowned scholars, like Marshal Rudolph and William Prosser, raised this issue long ago, and I commend Professor Woolley for bringing it back to the fore. However, as aforementioned, I do not believe it is correct, nor helpful, to impute Justice Brown’s introductory paragraph as “arrogance.” Nor is it helpful to look at it as part of a more systemic problem. Instead, by understanding Justice Brown’s decision as “judicial humour,” and situating it within that relevant legal scholarship, we can achieve a more fulsome understanding of some of the positives of such commentary. I should note that Professor Woolley has stressed that her “objection to Justice Brown was not his humour…[but] with writing a decision to ‘show [his] cleverness and erudition.’ To me, “humour” (especially of the legal variety) is inseparably attached to cleverness, and one cannot so easily separate the two.

Lucas K. Hori conducts an extensive review of the current legal scholarship and behavioural literature on judicial humour in “Bon Mots, Buffoonery, and the Bench: The Role of Humor in Judicial Opinions” (aside: if interested in similar work, please also see the equally comprehensive article “Judicial Humour In The Australian Courtroom” by Sharyn Anleu, Kathy Mack and Jordan Tutton). Hori carefully summarizes the work of behavioural scientist Arthur Burger, who breaks down humour into four theories: superiority theories, incongruity theories, psychoanalytic theories, and cognitive theories. Superiority theory is perhaps the most dangerous, and the one scholars like Woolley are the most concerned about. The superiority theory posits that we take pleasure from feeling that we are superior to others. For me, this theory runs the closest to the “arrogance” that Professor Woolley describes: those judges who craft their decisions to “show [their] cleverness and erudition.” On the other hand, the second theory, the incongruity theory, proposes that, at the root of humour are ‘the differences between the expected and the received, inconsistencies between circumstances and the person – basically a surprise, as seen in the normative structure of a joke…Because [a legal] opinion is a serious document, the reader expects its content to be dry and stern.” To me, this seems to be more in line with the objective, and the general reception, of Justice Brown’s writing. In my opinion, this type of humour is more than welcome in, and in fact is beneficial to, our legal system. Ultimately, Hori comes to a similar conclusion in terms of the two theories, and usages of humour:

Appropriate judicial humor will enhance rather than detract from core values….However, if the subject of judicial humor is the…litigants, it will very rarely be acceptable. The context of judicial humor is important….Appropriate judicial humor can have an important function in the courtroom. In addition to relieving tension, it can enhance procedural fairness which in turn can increase the perception of legitimacy of judicial authority. Humor which has these effects justifies the use of humor in a setting traditionally opposed to it.

As Hori aptly surmises, judicial humour makes opinions more readable, relatable and thereby more accessible. Indeed, humour not only makes an opinion much easier to read and understand, but it can also help crystallize a point, put it in context, and breathe life into the set of facts that the law has formalized. Or in the words of U.S. Judge Braswell Deen: “[a] sense of humour can complement fine judicial standards,…ward off the highly infectious disease ‘black-robe-itis,’ and…immunize Judges to the abhorrent judicial ailment known as the ‘divinity virus.’” Is this not the very thrust of Justice Brown’s opening paragraph? To juxtapose the law, and its lofty legal concepts, with something that is so true, and relatable to Canadian hearts: “the delight of everyone,” the game of hockey? Call it “arrogance,” if you wish. I call it accessible.

Third Period: Moving Forward

American Judge Alex Kozinski once wrote, “[H]umour is the pepper spray in the arsenal of persuasive literary ordnance: It is often surprising, disarming and, when delivered with precision, highly effective.” Going forward, excising judicial humour is simply not practical, nor helpful. Hori summarizes his article by providing advice for judges when using humor. As you read Hori’s suggestions (produced below), revisit Justice Brown’s introduction, and perhaps you will find, as I did, that his use of humour fits squarely into Hori’s idea of an effective use of judicial humour:

The legal profession prides itself on incisive and well-crafted writing….Preventing judges from using humour would ultimately quell the creation of unique opinions that employ creative means to convey difficult concepts. In the process, the legal profession would lose the tradition of fun opinions. Nonetheless, if they intend to use humor in their opinions, judges should keep in mind two guiding principles. First, judges would be well served to keep humor brief. Humor should not overwhelm the substance of the opinion but should provide a respite from the serious legal matter….Second, judges should critique their writing from the perspective of the parties to the case. Does the humor offend, or is it merely in good fun?….The superiority theory suggests that ridicule and belittlement are effective ways to invoke laughs. Although such scorn can be amusing for detached readers, it is not appropriate in judicial writing….Permitting these members of the bench to write in creative, humorous ways will add interest and clarity to legal orders.

One of Professor Woolley’s main quarrels with Justice Brown’s decision is that it takes the spotlight away from the parties (for whom “everything is at stake”) and shines it on his own wit. However, Justice Brown’s language never moves past “good fun” to rise to anything close to “ridicule and belittlement.” In fact, Justice Brown’s use of humour does not last beyond the initial paragraph.

To understand Justice Brown’s opening paragraph, one also needs to read beyond it, to the clear, simple and persuasive prose that characterizes the rest of the decision. One marvels at the way Justice Brown finds a way to take the complex terminology and rules that surround customs classification law, and present them in an orderly, comprehensible package for the unfamiliar reader. Once you arrive at the end of the decision, reread the opening paragraph, and sense Justice Brown’s frustration with how detached this area of law seems to have become from our lived realities. What I saw in rereading the opening paragraph was not an arrogant judge flaunting his abilities, but rather a gifted and adept writer, carefully weaving wit into a form of writing which is, by nature, very serious, in order to comment on its accessibility.

**

Author’s Note: The first part of the article’s title, “More Than Mere Trimming” comes from paragraph 13 of the decision: “The Canadian International Trade Tribunal (“CITT”) then considered whether the gloves were classifiable under heading 62.16. While it found that they conformed to the type of goods (“[g]loves, mittens [or] mitts”) described in that heading, it recognized that the Explanatory Note to heading 62.16 directed it to apply the General Rules if the articles contained non-textile material that constituted “more than mere trimming”. Since the hockey gloves contained plastic padding that was more than mere trimming, the CITT applied Rule 2(b) of the General Rules…which led the CITT to “extend the scope” of the heading in order to classify the goods as “[g]loves, mittens [or] mitts.”

Join the conversation