Parliament Must Leave Door Open for Offender Rehabilitation: SCC in R. v. Bissonnette

On May 27, 2022, the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) decided R. v. Bissonnette, 2022 SCC 23 [Bissonnette], in which the Court considered the constitutional status of s. 745.51 of the Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c C-46 [“Code”].

In Canadian criminal law, an offender convicted of first-degree murder automatically receives a sentence of life imprisonment, with no possibility of parole for 25 years. In the case of an offender convicted of multiple murders, the impugned provision allows a court to stack the 25-year parole ineligibility period for each murder, such that the offender will have to serve a life sentence with no realistic possibility of parole in their lifetime.

The SCC unanimously held that s. 745.51 of the Code violated s. 12 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which guarantees the right not to be subjected to cruel and unusual treatment or punishment, and that it was unjustified under s.1 of the Charter. The Court held that the provision effectively meant that offenders receiving such sentences would be dismissed as lacking even the capacity to reform, which is incompatible with Charter values.

Background and Facts of the Case

Over the years, the province of Quebec has made several, much-criticized attempts to regulate some aspects of religious groups’ ability to practice their faith, including banning displays of symbols of faith in the public sphere in its Act Respecting the Laicity of the State, SQ 2019, c 12. Each such attempt was followed by increased public debate and tensions between religious minorities and those committed to less accommodating conceptions of secularism.

This was the context in which the events of the present case took place, in January 2017. It was one of the deadliest mass shootings in Canadian history, and left the Canadian Muslim community reeling in its wake. The accused, 27-year-old Alexandre Bissonnette, pleaded guilty to 12 charges against him, including 6 counts of first-degree murder, after firing a semi-automatic rifle and a pistol at worshippers in the Great Mosque of Quebec.

The shooting prompted renewed public discourse on racial and religious intolerance driven by extreme right-wing politics, as more information on Bissonnette’s motives became public during his trial. Bissonnette’s internet search history revealed that he was influenced by extreme right-wing ideologues. Bissonnette also reportedly told police that he feared his family would be attacked by “Islamic terrorists.”

Judicial History

At trial, the Crown requested that the court apply s. 745.51 of the Code. This would mean that the offender would serve the parole ineligibility period of 25 years consecutively for each of the 6 first-degree murder convictions, for a total of 150 years.

The trial judge held that the provision violated ss. 12 and 7 of the Charter, and that this violation could not be justified under s.1 of the Charter. As a remedy, he read in the judicial “discretion to choose the length of the additional ineligibility period to impose on an offender” (Bissonnette SCC, para 18). Accordingly, the judge sentenced the offender to concurrently serve a 25-year parole ineligibility period for 5 of the 6 first-degree murder convictions. The judge then added a 15-year period for the sixth count, to be served consecutive to the 25-year period, making a total parole ineligibility period of 40 years.

On appeal, the Quebec Court of Appeal (“QCCA”) held that while the trial judge was correct in finding that s. 745.51 unjustifiably violates ss. 7 and 12 of the Charter, he had erred in applying reading in as the remedy to reformulate the provision. It then declared the provision unconstitutional with immediate effect, and ordered the offender to serve the 25-year parole ineligibility periods for each count of first-degree murder concurrently.

On appeal, the SCC clarified the following:

- Does the impugned provision violate s. 12 of the Charter, and if so, can it be justified under s.1 of the Charter?

- If the impugned provision cannot be justified, what is the correct remedy?

The Court’s Decision

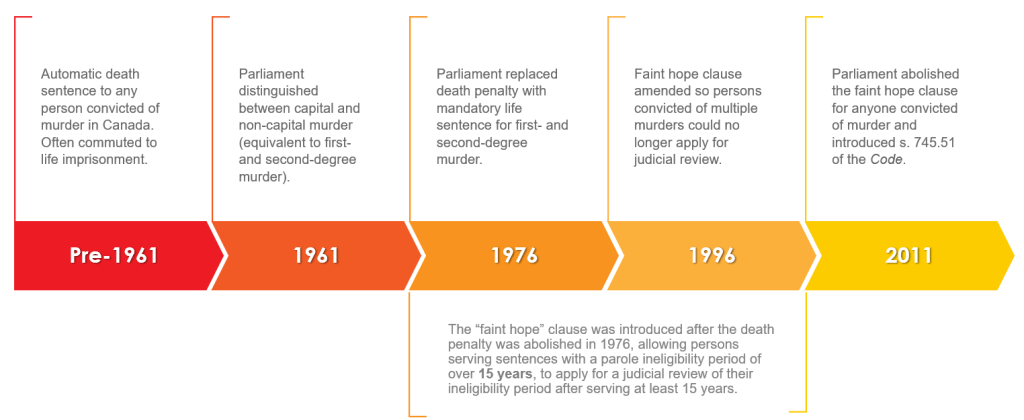

Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Richard Wagner notes that a sentence of life imprisonment without a realistic possibility of parole would be “one whose severity is without precedent in this country’s history since the abolition of the death penalty and corporal punishment in the 1970s” (Bissonnette SCC, para 3).

The SCC reaffirmed that the purpose of s.12 is “to protect human dignity and ensure respect for the inherent worth of each individual” (Bissonnette SCC, para 5), and clarified that there are two categories to the s. 12 right not to be subjected to cruel and unusual punishment. The first involves punishments whose effects are grossly disproportionate. Determining this requires courts to undertake a contextual analysis of the circumstances of the case and the offender’s background and personal characteristics. The second, narrower category of punishments are those that are intrinsically incompatible with human dignity and would always be grossly disproportionate, no matter the circumstances in which they were applied.

The Court held that denying offenders any possibility of parole eligibility in their lifetime would constitute punishment that is intrinsically degrading. As such, it would fall into the category of punishments that are intrinsically incompatible with human dignity. This would undermine one of the criminal justice system’s purported objectives of rehabilitating offenders by presumptively negating the offender’s capacity to repent and reintegrate into society.

The Court stated that the criminal justice system must impose “just sanctions” that serve its sentencing objectives, like denouncing conduct which offends society’s moral values, deterring the offender and the public from criminal activity in the future, and rehabilitating offenders to become law-abiding citizens. Balancing these objectives requires courts to follow the principle of proportionality, such that no punishment exceeds the “moral blameworthiness of the offender and the gravity of the offence” (Bissonnette SCC, para 50). Therefore, to impose a sentence that prioritizes one objective, deterrence, at the complete expense of another that is fundamentally linked to the protection of human dignity, rehabilitation, would not be compatible with Canadian law.

The Crown made no arguments to justify the impugned provision under s.1 of the Charter. The Court held that grossly disproportionate punishments under s.12 would be highly unlikely to satisfy the s.1 test in any event. As such, the SCC agreed with the lower courts’ decisions that s.745.51 violated the Charter in a manner that could not be justified.

Finally, the Court determined that the trial judge had erred in applying reading in as a remedy. This was because Parliament’s unequivocal intention was to permit courts to order fixed 25-year periods of parole ineligibility to be served consecutively, rather than concurrently. Accordingly, the Court declared the impugned provision unconstitutional with immediate effect, and applied retroactively to the date of its enactment, given the high stakes involved for individuals affected by it.

Commentary

Door to Rehabilitation Must Be Left (Barely) Open

At the heart of the Court’s discussion is the need for courts to balance retribution as a sentencing objective on the one hand and rehabilitation on the other. In the context of crimes that confer a high degree of moral blameworthiness on the offender, as in first-degree murder convictions, denunciation and deterrence weigh heavily in the balance against rehabilitation of the offender. Nonetheless, courts are required to issue a sentence that is neither too lenient, nor grossly disproportionate to the crime and the circumstances of the offender.

This is a tall order, made even more morally complex in circumstances that involve an offender inflicting deep and irreversible harm to a marginalized group. Yet the understandably visceral reaction against those who commit such crimes must not allow us to completely lose sight of the fundamental values that underpin Canadian society and how it governs itself. How a society treats its most vulnerable provides a measure of its humanity. The same is true for how it treats the “vilest of criminals.”

Though the Court grounds its analysis on human dignity, it is a notoriously difficult concept to define. Crafting a legal argument underpinned by such an abstract concept is bound to be analytically imprecise. The heavily contested nature of human dignity leads one to question whether, in the judicial context, it is simply a stand-in for judges’ personal morality. If this is true, it would be reasonable to conclude that the concept has little utility in guiding courts to make consistent decisions. Who is to say whether the holding endorsed by the SCC in this case meets its own standard of protecting the inherent worth of human beings, if the standard itself is subject to the ethical ideals of whoever is invoking it?

Perhaps in recognition of this, the Court took pains to supplement its decision with a comparative analysis of mandatory sentences for first-degree murder in foreign jurisdictions and Canada’s obligations pursuant to international treaties and agreements it has ratified. This served two purposes. First, illustrating that Canadian criminal law on parole eligibility for first-degree murder is more punitive than some other Western liberal democracies, even before the provision was enacted. Second, international instruments also ground its requirements to give offenders an opportunity for rehabilitation on human dignity.

Variations between countries do not come about in a vacuum—they reflect the historical and prevailing social, political, and religious value systems of each country. In constitutional democracies, the particular balance between competing ideals of the criminal justice system is typically struck between the legislature and the judiciary.

An Ideological Divide

Whether one believes that the Court goes too far, or falls short of its goal of preserving individual worth and dignity is perhaps primarily ruled by whether one values retributive justice over rehabilitative justice. Conservative politicians for their part, responded with calls to invoke s. 33.1 of the Constitution Act, 1982, to reinstate the struck down provision, notwithstanding ss. 2 and 7-15 of the Charter. The Liberal government and the NDP stated that they would respect the Court’s decision. This split may be explained by the ideological divide between the conservative ethos of being tough on crime and progressive ideals that pay attention to the welfare of both victims and offenders.

While typically we see this tension play out between political parties, sometimes, as in this case, a similar tension is evoked in the “dialogue” between Parliament and the judiciary. In the interests of democratic decision-making, courts generally defer to legislative intent, but only to the extent that it is permitted by constitutional constraints on government action against individuals. In finding that Parliament’s intent was categorically at odds with Canadian constitutional values, the SCC had to resort to the relatively rare remedy of striking down the impugned provision in its entirety.

Those who are troubled by the trend towards harsher punishments may applaud this decision for emphasizing the need to retain our humanity, even when dealing with the most unsympathetic of people. However, the deference that courts afford Parliament means that, not only are we left with a compromise that is still more severe than the status quo in other countries like Canada, it is also far from a guarantee that the next iteration of the provision will not also violate Charter rights. What is uncontestable is that, in the meantime, the burdens of the system continue to disproportionately fall on racialized and economically vulnerable communities.

It is impossible to determine to what degree the broader socio-political context drove Bissonnette to carry out such a heinous act of violence against innocent people. What we do know is that he found support for bigotry and Islamophobia in the far-right incendiary rhetoric that has been gaining traction in mainstream media and politics across the globe. Imposing harsher sentencing on those who act on such rhetoric to catastrophic effect may be an adequate solution to some. But embracing compassion in all aspects of public life does more to combat the prejudice and discrimination that motivated the shooting, and shamefully, continues to adversely affect the lived realities of Canadian Muslims.

Join the conversation