Report from China: Supreme People’s Court

The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) is the highest court in the judicial system of the People’s Republic of China (PRC, commonly known as China). Hong Kong and Macau, as special administrative regions, have their own separated judicial systems based on British common law traditions and Portuguese civil-law traditions respectively, and are not within the jurisdiction of the SPC. Taiwan, regarded as an inseparable part of China, has its self-governing judicial system due to complicated historical background.

The Hierarchy of the Judiciary

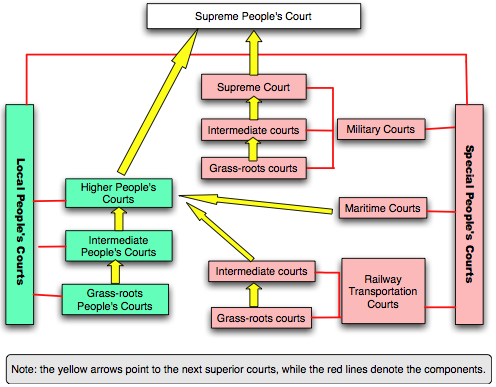

Under the Constitution and the Organic Law of the People’s Courts (OLPC), the system of courts in China consists of the Supreme People’s Court, local people’s courts and special people’s courts. The local people’s courts are established in accordance with the administrative divisions, while the special people’s courts are set up where necessary. The following is a chart of the generally four-level court system.

The SPC is the highest trial court in China, and it is also the highest supervising organ over the trial practices of local people’s courts and special people’s courts at various levels, directly responsible to the National People’s Congress (NPC) and its Standing Committee. The SPC includes over 200 justices consisting of the president, vice presidents, presiding judges, vice presiding judges and judges. Since March 1998, the president of the SPC and Chief Grand Justice has been Xiao Yang. The power of appointment and removal of the president, who remains in office for no more than two successive terms with each term of five years, lies with the NPC, while the other justices are appointed and removed by the Standing Committee of the NPC.

The higher people’s courts (HPC) are instituted at the levels of provinces and autonomous regions as well as municipalities directly under the Central Government. The intermediate people’s courts are established at levels of prefectures (including autonomous prefectures), provincial capitals (including cities under direct control of the provincial or autonomous region government), relatively big cities and within the municipalities directly under the Central Government.

The Grass-roots people’s courts are established at county or autonomous county levels, and in urban districts or cities without districts. To facilitate lawsuits, the grass-roots courts may set up tribunals in towns. The special people’s courts are set up in special departments for special cases where necessary. Currently, China has special courts handling military, maritime, railway cases.

Military courts operate at three levels: grass-roots; Great Military Region, Services and Arms; and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Court. The PLA Court is the supreme military court. Great Military Region and Services and Arms Courts are intermediate courts set up in great military regions, the navy, the air force, the Second Artillery Army and the PLA General Headquarters. Grass-roots military courts consist of tribunals set up in armies, provincial military regions, naval fleets, and air forces within Great Military Regions and in army units deployed in Beijing directly under the headquarters.

Maritime courts are set up to try first instance maritime or sea-shipping cases for the purpose of exercising judicial jurisdiction over maritime affairs. The trial activities of the maritime courts are supervised by the HPC in the same regions.

Railway transportation courts are established along railways. There are two levels of railway transportation courts, namely the intermediate railway transportation courts of the railway administrations and grassroots courts of the railway branch administrations. The trial activities of the intermediate railway courts are supervised by the HPC in the same regions.

Every court, except the special courts, runs smaller tribunals of criminal, civil, administrative trials and other tribunals set up according to actual needs.

The Structure and Responsibilities of the SPC

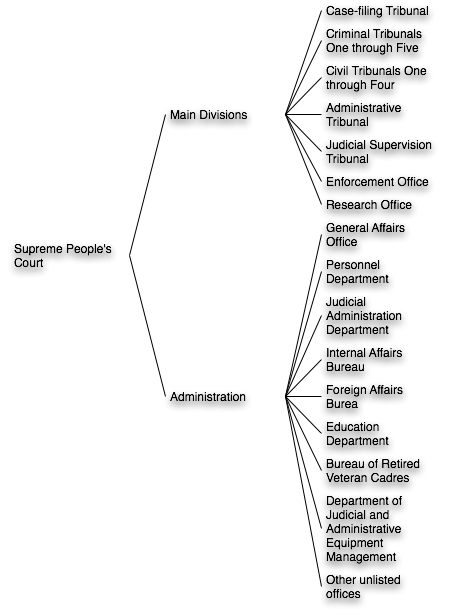

The SPC is probably the biggest court in the world in terms of personnel and organization, operating twelve tribunals and dozens of important offices and administration staff departments displayed by the following diagram.

The SPC shoulders three significant responsibilities pursuant to the Constitution and the OLPC:

Trial Practice

The SPC tries cases of first instance that fall within its jurisdiction as provided by law or deemed necessary to be heard by itself; hears appeals against the judgments and decisions of higher and appropriate special people’s courts; hears protests lodged by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate through judicial supervision procedure; deals with cases of unidentified jurisdiction accepted by the lower courts, reviews and approves the death penalty sentences.

Judicial Interpretation

The SPC has the authority to give judicial interpretation on the specific application of the law, so as to solve knotty legal issues in the course of trial, and to ensure the uniformity in applying the law. The judicial interpretation shall take binding effect and must be observed by all courts in China, once it is adopted and announced, subject to decision, by the judicial committee of the SPC.

Judicial Administration

The SPC is responsible for the administration of itself, to assists in the administration of personnel quota and structural settings of all the people’s courts, to arrange judicial communications with foreign counterparts and international organizations, to take charge of finance, equipment and judicial science and technology, and to guide lower people’s courts in their judicial administrative work.

Recent Focuses

Retrieving Sole Authority over Death Penalty

On October 31, 2006, the Standing Committee of the NPC, China’s top legislature when the NPC is not in session, adopted an amendment to the OLPC, ending a 26-year practice of the SPC delegating the power to review some death sentences to the HPC.

This amendment represents a policy change that has been in the works a long time.

The 1954 OLPC prescribed that the death penalty cases should be approved by the SPC or the HPC. In 1957 the Fourth Session of the First NPC adopted a resolution that all the death penalty cases should be reviewed and approved by the SPC from then on. The SPC then reviewed all the death sentences during 1958-1966.

Unfortunately, the SPC’s power of the review was ignored during the decade-long Cultural Revolution from 1966-1976.

In July, 1979, the Second Session of the Fifth NPC adpoted the the Criminal Law of the PRC and the the Criminal Procedure Law of the PRC and the new OLPC, which unanimously prescribed that all death sentences, except for those according to law should be decided by the Supreme People’s Court, shall be submitted to the Supreme People’s Court for verification and approval.

However, a “hit hard” campaign was launched right after the passage of this law, amid social unrests of that era. Because of the “punish hard, punish fast” hit-hard campaign and a trend of increasingly harsh punishment, the Standing Committee of the NPC decided to give the higher people’s courts final approval over some types of serious crimes—those gravely endangering public safety like murder, rape, robbery, etc. In 1980 and 1981 the NPC adopted two separate resolutions memorializing this change into law. And in 1983, the NPC amended the OLPC, finally and firmly establishing this change, which clearly gave the SPC the authority to delegate death penalty review down to the higher people’s courts.

Duly authorized, the SPC promptly issued a notice delegating that review power. In order to “punish hard” some courts pushed the limits of sentencing and issued the most severe punishments allowable. As the “hit hard” campaign became more entrenched and when social order gradually restored, problems cropped up while various cases of wrongful convictions leading to executions became public.

In the late 1990s, people started to rethink the “hit hard” campaign, and it was suggested that the SPC be reinstituted as having the sole power to review death penalty cases. Academics began to cautiously discuss the trend in China’s use of death penalty, but the debate did not become widely public. Nevertheless, the practice of handling both appeals of death sentences and final reviews by the higher people’s courts has drawn sharp criticism in recent years in the wake of some highly-publicized miscarriages of justice.

Since the beginning of 2005, China’s media have exposed a series of misjudged death penalty cases and criticized courts for their lack of caution in meting out capital punishment. Experts and common people pushed for recentralizing the power of approving the severest criminal punishment. The SPC also put reclaiming this power of review on the agenda of its official Second Five-Year Plan for Court Reform dated Oct. 26, 2005.

A decision finally came out On Oct. 31, 2006: the Standing Committee of the NPC adopted a resolution amending Art. 13 of the Organic Law on People’s Court to read in its entirety as follows:

Death sentences, except where imposed by the Supreme People’s Court according to law, should be reported to the Supreme People’s Court for review and approval.

This amendment has come into effect since January 1, 2007. It is believed to be the most significant reform on death penalty in China in the past two decades, which greatly boosts the protection of human rights.

Expansion of Tribunals and Judges

For having adequate personnel to review death penalty cases, the SPC has created two more vice president posts, two more full-time judicial committee member posts and three more criminal tribunals to the previous two and expanded the death penalty review team from 50 to 100 judges which is still expected to rise.

Many of the judges recruited to carry out the death penalty reviews are qualified judges from local people’s courts, experienced lawyers and law professors. They have finished their three-month training at the SPC and will be on one-year probation before officially assuming office.

Death Penalty Review

The review of each death sentence shall be made by a panel of three judges, who must fully review the evidences, law application, measurement of penalty, and the litigation process in the previous trial and should hear the defendant out either in person or by letter, before they reach the final decision. If judges find the evidence is inadequate, the measurement of the penalty improper, or the litigation process illegal when reviewing the death sentence, they should submit the case to the SPC’s judicial committee. The judicial committee will further consider the case with a procurator in attendance from the Supreme People’s Procuratorate. Death penalty cases without an open second trial will not be reviewed by the SPC, but will be sent back to the court of second instance for open trial.

As a result of the review, the SPC shall send back the death sentences to the HPCs for retrial if errors are found in judgement, instead of directly changing the sentence, according to a regulation released by the SPC on Feb. 27, 2007. Under the new regulation, the SPC shall only change the original death penalty sentences in cases involving individual criminals facing multiple death sentences, or multiple criminals facing death penalties. The new regulation guarantees that death sentences are handed out with caution by ordering retrials, which also improves the efficiency of the SPC death penalty reviews.

The SPC is strengthening supervision and guidance to intermediate and higher courts in cases where death penalties are imposed and is drafting a notice to further regulate the trial process of courts of first and second instance so as to root out corruption and nepotism among judges. “Judges who are found to have taken or offered bribes, or have abused their power will be instantly deposed, and will face criminal charges if their actions break the law,” said Xiao Yang, president of the SPC.

While enforcing its crackdown on crimes, China is becoming more prudent and strict while exercising death penalty. “China’s consistent principle is to maintain the death penalty, but use it strictly,” said a SPC spokesman, “China’s courts will adhere to this principle, hand out death penalty with great caution and try to minimize its use to ensure capital punishment is only given to a handful of criminals who commit extremely notorious crimes.”

For further information on the Supreme People’s Court of the People’s Republic of China, including legislation, judgments, typical cases, work reports, judges and press releases, please visit the Supreme People’s Court website, at http://www.court.gov.cn.

Join the conversation