Understanding the Right to Counsel: SCC Decides R v Lafrance

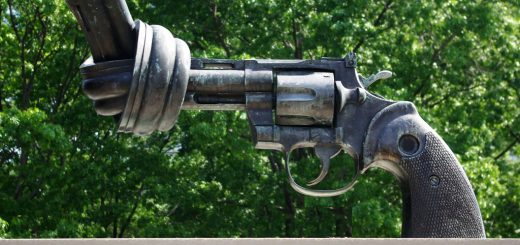

We’ve all seen a classic interrogation scene in movies or on TV. The police sit an accused person down, start asking questions, and hope he doesn’t “lawyer up.” What we understand from this is simple: once you ask for a lawyer, the police can’t interrogate you without your lawyer present. And, perhaps more importantly, everyone has a right to counsel—everyone is entitled to have a lawyer present when up against a state actor like the police. Any person could be forgiven for believing this widespread portrayal of the legal process is accurate.

But it’s not quite right.

Canadians do have a right to counsel – guaranteed by section 10(b) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms [Charter]. But the scope and content of that right would probably surprise the average Canadian.

So, what exactly does the right to counsel guarantee? The Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) considered section 10(b) most recently in R v Lafrance, 2022 SCC 32 [Lafrance].

Facts of the Case

On March 17, 2015, a man named Anthony Yasinski died after being stabbed in the neck. The last person known to have contacted him before his death was Mr Nigel Lafrance, a 19 year-old Indigenous man. Mr Lafrance was a recent high school graduate and had little, if any, prior experience with law enforcement.

On March 19, 2015, a team of eleven armed police officers wearing bulletproof vests entered Mr Lafrance’s home at 6:50 am to execute a search warrant. Mr Lafrance, who was asleep at the time, was awoken by three police officers who ordered him to dress and leave the home. Once Mr Lafrance was outside, Sergeant Eros asked him to confirm his identity and come to the police station for an interview.

Sergeant Eros asked Mr Lafrance to give a statement about Mr Yasinski’s death. He told Mr Lafrance that doing so would be “completely voluntary” (Lafrance, para 10). Mr Lafrance agreed to go give a statement, and chose to accept a ride to the station with officers in an unmarked police car. Sergeant Eros took Mr Lafrance to an interrogation room in a “secure environment”—Mr Lafrance was free to leave, but while he remained at the station, he was to be accompanied everywhere by an officer, even to the washroom.

During the interview, Sergeant Eros passed on information given by Mr Lafrance to the team executing the search so they could seize items of interest. Mr Lafrance also consented to give the police his fingerprints, DNA, cellphone, and clothing.

On April 7, 2015, police arrested Mr Lafrance for Mr Yasinski’s murder. Police informed Mr Lafrance of his right to legal counsel, and Mr Lafrance called Legal Aid. Mr Lafrance had never spoken to a lawyer before. When the call ended, police asked Mr Lafrance if he had understood the legal advice he received from the lawyer. Mr Lafrance said yes.

Police questioned Mr Lafrance for several hours. At that point, Sergeant Eros made clear to Mr Lafrance that his version of events was not believed and the police were certain he had killed Mr Yasinski. Mr Lafrance asked to speak with his father before continuing, saying it was his “only chance of getting a lawyer” (Lafrance, para 17).

Sergeant Eros told Mr Lafrance that he had already spoken to a lawyer, and further that he would not be able to have a lawyer in the room during questioning. Mr Lafrance confessed to killing Mr Yasinski.

Decisions of Courts Below

At trial, Mr Lafrance sought to exclude his confession from evidence. He argued that the police had breached his right to counsel under section 10(b) of the Charter on both March 19 and April 7. The trial judge held that Mr Lafrance had not been detained on March 19, and so no section 10(b) rights were engaged. The trial judge also held that Mr Lafrance was not entitled to a second opportunity to speak with a lawyer on April 7, and the call allowed to Legal Aid was sufficient to fulfil his right to counsel. The trial judge allowed the evidence to be admitted. The jury convicted Mr Lafrance of second-degree murder.

Mr Lafrance appealed to the Court of Appeal for Alberta. The majority of the Court of Appeal allowed the appeal and ordered a new trial, with Mr Lafrance’s confession excluded. The Crown appealed to the SCC.

SCC Holds Rights to Counsel, etc, were Breached

Writing for a majority of the SCC, Justice Russell Brown considered three fairly narrow issues:

1. Did the police detain Mr. Lafrance and breach his s. 10(b) right to counsel on March 19, 2015?

2. Did the police breach Mr. Lafrance’s s. 10(b) right to counsel by refusing to allow him to have a further consultation with a lawyer on April 7, 2015?

3. If the answer to either or both of the foregoing is “yes”, would the evidence obtained therefrom bring the administration of justice into disrepute, such that it must be excluded under s. 24(2)? (Lafrance, para 19)

Justice Brown answered all three questions “yes.” Police detained Mr Lafrance on March 19 and failed to advise him of his right to counsel; police breached Mr Lafrance’s right to counsel a second time when they refused to give a second consultation on April 7; and the Court excluded the evidence.

The majority applied the factors listed in R v Grant, 2009 SCC 32: the circumstances, the nature of the police conduct, and the particular characteristics of the individual (Lafrance, para 63). The police’s conduct provided the necessary context to support the majority’s finding that Mr Lafrance was detained. Police arrived at an early hour, in great numbers, armed and wearing bulletproof vests. Justice Brown pointed out that exerting control over the home, even though it was pursuant to a warrant, in this case extended to exerting control of a person (Lafrance, para 47). Police also questioned Mr Lafrance in a secure environment at the police station. Personal characteristics of Mr Lafrance were important, too: he was young and inexperienced with law enforcement, which suggested he had a lesser understanding of his rights and was more likely to believe he had no choice but to comply.

Justice Brown also gave Mr Lafrance’s Indigenous identity appropriate consideration. He referenced the overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in the criminal justice system. He also acknowledged the historical failures of police in serving Indigenous populations, which often cause fear and mistrust to colour Indigenous people’s present-day interactions with police. However, Justice Brown discussed Mr Lafrance’s Indigeneity with an even hand:

This consideration will often weigh in favour of finding a detention, but not invariably. A court cannot simply assume that all Indigenous people’s experiences with the police are Charter non-compliant or otherwise oppressive (Lafrance, para 58).

Because there was little evidence that Mr Lafrance’s Indigeneity had played a role in this specific encounter, this part of his circumstances did not weigh heavily. However, as the analysis was objective, it nevertheless weighed in favour of finding a detention.

The minority found no detention, because the police on several occasions told Mr Lafrance that he was free to leave, that he need not answer their questions, etc. That he was informed his compliance was voluntary, and said he understood that, was enough to satisfy the minority that Mr Lafrance believed he had any choice. While they agreed that police conduct can negate the effect of their words, it is notable that the minority gave no consideration to the police’s manner of entry, and limited discussion of Mr Lafrance’s Indigeneity. And while they acknowledged that the “threshold may be lower for vulnerable individuals who are unfamiliar with their Charter rights,” they failed to adjust their threshold accordingly (Lafrance, para 125). It was not obvious to them, as it was to me, that they had just described the exact situation of Mr Lafrance.

Section 10(b): the Detained Person’s Right to Counsel

Section 10(b) of the Charter reads:

10 Everyone has the right on arrest or detention:

(b) to retain and instruct counsel without delay and to be informed of that right.

The SCC set out the principles governing the right to counsel in R v Sinclair, 2010 SCC 35 [Sinclair]. The right to counsel has two parts: an informational component and an implementational component (Lafrance, para 72).

The informational component of section 10(b) requires that police advise detained persons that they have a right to counsel (Lafrance, para 72).

The implementational component of section 10(b) requires that police allow detained persons to exercise their right to counsel. It places two duties or obligations on police:

- that police not question a detained person until they have had a reasonable opportunity to speak to a lawyer about their situation (Lafrance, para 72; citing Sinclair, para 27); and

- that police allow a detained person to speak with a lawyer again if a change or development makes another consultation necessary, in the sense that the detained person is not only aware of their right to counsel but understands how to exercise it (Lafrance, para 72; citing Sinclair, para 53).

Sinclair held that a single opportunity to speak to a lawyer can satisfy the constitutional obligation that police have to allow a detained person to exercise their right to counsel (Lafrance, para 171). However, Sinclair also sets out three situations in which a further opportunity to consult counsel can be required:

- The police try to use “non-routine procedures” that a lawyer would not have considered initially;

- The jeopardy of the situation changes in a way that the lawyer’s initial advice may have been inadequate; or

- The police have reason to suspect the detained person may not understand their rights (Lafrance, para 72).

Mr Lafrance’s request to speak to his father because it was his “only chance of getting a lawyer” was, for the majority, a reason to suspect that he didn’t understand his rights. The situation therefore fell within the third Sinclair exception, and Mr Lafrance was entitled to a second consultation with a lawyer.

Justice Brown placed a good deal of emphasis on the detained person’s understanding of their rights. For the right to counsel to be satisfied, the detained person must not only have received advice, but understood that advice and how to exercise it. It is not enough that a person has spoken to a lawyer and been told they have a right to be silent, for example; the person must understand not only that they can choose not to speak to the police, but also the benefits and drawbacks of both speaking to the police and remaining silent (Lafrance, para 73).

The minority judgement preferred to construe Mr Lafrance’s misunderstanding as a simple misunderstanding, and not overall important. According to the minority, mere confusion about one’s rights or the scope of one’s right to counsel is not enough for the constitution to intervene. That a person mistakenly believes that they have a right to have a lawyer present for questioning, as Mr Lafrance believed, does not provide the “objective basis” necessary to allow a second opportunity to speak to counsel (Lafrance, para 183).

The SCC has identified the purpose of section 10(b) as ensuring that detained persons have received advice on their situation. It therefore makes sense that section 10(b) would also demand that the detained person understand their situation, including the effects of any choices they make to cooperate or not.

The detained person must also meaningfully understand how to cooperate or not. A detained person has a right to legal advice on “strategies for resisting cooperation” as part of the section 10(b) guarantee (Lafrance, para 73). To me, this illustrates the depth of what section 10(b) requires. Many people consider the right to counsel as an important part of balancing the power between the state and a detained individual (indeed, both the majority and dissent in Lafrance discussed this power imbalance in their reasons).

What Does Section 10(b) Protect?

The television lawyer, who walks into the interrogation room and demands that the interview ends, is paradigmatic of the individual’s protection against the overbearing power of the state. So it may surprise some people to know that one’s right to counsel, at least in Canada, is satisfied by a single phone call to a lawyer. There is no right to have a lawyer in the room.

And there’s no “lawyering up” in Canadian law, either—at least, not in the popularized, television sense. Once a person has had the opportunity to speak to a lawyer, the police are free to continue questioning them.

However, as far as can be done, Justice Brown’s construction of the rights conveyed by section 10(b) seem to reasonably balance the importance of the state’s ability to investigate crime with the individual’s right to protection from state power. Justice Brown does an admirable job of not just circling the point, but hitting it square on the head :

[T]he detainee is in a position of disadvantage relative to the state. … This disadvantage is no small matter, particularly given that the police may employ tactics such as lying during an interrogation. It is only by ensuring that detainees obtain legal advice that accounts for the particular situation they face, conveyed in a manner they can understand, that s. 10(b) can meaningfully redress the imbalance of power between the state (whose agents know the detainee’s rights) and the detainee (who may not) (Lafrance, para 77).

Justice Brown’s analysis rests on the earlier cases of R v Grant and R v Le, 2019 SCC 34 (the latter of which was co-written by Justice Brown) to support his liberal and purposive approach. “The work done by our jurisprudence,” he writes, “would be undone by an impoverished understanding of s. 10(b)’s protections, inconsistent with Sinclair itself and corrosive of the liberty of the subject” (Lafrance, para 77).

So, what does the right to counsel protect? For now, the right of a detained person to speak with a lawyer, once, about their specific situation. It protects the detained person’s right to not only receive advice, but understand it. What it does not guarantee is protection from the oppressive circumstances a detainee may be subjected to. It is on the individual, alone, to hold fast against the might of a state determined to break them.

As far as the constitution is concerned, a detained person who has been told they have a right to be silent may have all the instructions they need to withstand a police interrogation: say nothing, do nothing, so long as you understand the consequences. And if police interrogation tactics, designed to stress you out so you’ll talk, in fact stress you out, and you talk? Too bad.

It seems, to me, quite a hollow right.

Join the conversation