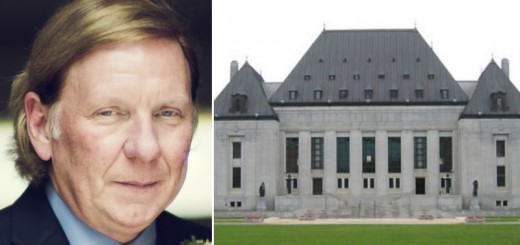

U.S. Supreme Court Speculation: John Paul Stevens May Soon Retire

Not long after Justice David Souter announced his retirement from the U.S. Supreme Court and Justice Sonia Sotomayor was confirmed as his replacement, the legal blogosphere lit up last week with reports that Justice John Paul Stevens may retire next year. The court’s most aged and arguably most “liberal” member, Justice Stevens confirmed through a spokeswoman Tuesday that he has only hired one law clerk for the 2010/2011 judicial term. Sitting justices typically hire a full complement of four clerks, while retired justices typically hire one.

At 89, Justice Stevens is the second-oldest justice in the U.S. Supreme Court’s history; with nearly 39 years on the bench, he is also the seventh-longest-serving justice. Self-described as “pretty darn conservative” and appointed by a Republican President, his views have matured over time and increasingly tended left as the Supreme Court’s ideological centre tended right. Retiring during a Democratic presidency would help ensure that a moderately liberal justice is appointed in his stead, thereby impeding the court’s conservative creep and preserving a lengthy jurisprudential legacy.

However true the retirement rumours, and although I deign to anticipate the official leaving of such a vigorous and dynamic person from the U.S. Supreme Court, it seems fitting to take pause and reflect upon Justice Stevens’ impressive personal and professional contributions to the common law.

Stevens’ Shift Leftward

Justice Stevens settled in Washington by way of Chicago, where he was a prominent antitrust lawyer. He was then appointed on the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, until President Gerald Ford elevated him to the Supreme Court in 1975. For his first few years at the Supreme Court, Justice Stevens maintained a moderately conservative record on a stable court. His subsequent turn to the left was hastened by the reality that, as he himself put it: “every judge who’s been appointed to the court since Lewis Powell has been more conservative than his or her predecessor. Except maybe Justice Ginsburg.”

It would, however, be incorrect to regard Justice Stevens’ judicial philosophy as only perceiving to shift in relation to a right-skewing ideological centre. In fact, he emerged as an improbable leader of the Supreme Court’s liberal wing, ardently defending individual rights against the collective (especially with regard to abortion, LGBT issues, and the death penalty) and arguing for greater oversight of executive power.

A Civil Libertarian Streak

Although not so closely associated with the abortion issue as his long time colleague and author of Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, Justice Harry Blackmun, Justice Stevens has long supported women’s privacy interests against the state. He defended and counseled Justice Blackmun during a long series of decisions “eating away” at Roe, including Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists, 476 U.S. 747; Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, 492 U.S. 490; and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833. Demonstrating great respect for the precedent and an idiosyncratic eloquence during deliberations in Webster, Justice Stevens stated that

As you know, I am not in favo[u]r of overruling Roe v. Wade, but if the deed is to be done I would rather see the Court give the case a decent burial instead of tossing it out the window of a fast-moving caboose.

Justice Stevens’ protection of privacy rights testifies to his distinctly civil libertarian approach to many social issues. For example, he filed a pithy dissent in Bowers v. Hardwick, 478, U.S. 186, the case upholding a Georgia sodomy law which incorrectly and offensively criminalized sexual relations between consenting homosexual adults. It is “a liberty case for me,” Stevens said in conference, because “only prejudice supports the distinction” in law between same-sex and opposite-sex couples. He wrote presciently that “[f]rom the standpoint of the individual, the homosexual and heterosexual have the same interest in deciding how he will live his own life.” This position was eventually adopted by the Supreme Court in the Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558, which invalidated homosexual sodomy laws nationwide.

To identify another case in this vein, Stevens’ majority opinion in Wallace v. Jaffree, 472 U.S. 38 (invalidating an Alabama statute which authorized “silent mediation or voluntary prayer” in public schools) lucidly articulates a secular, civil libertarian approach to the Establishment Clause founded in “individual freedom of mind” to accept or refrain from accepting the creed of the majority.

Justice Stevens has demonstrated similar inclinations in criminal appeals. Researchers such as Christopher E. Smith who surveyed his Supreme Court jurisprudence between 1995 and 2001 have indicated that, of all sitting justices, he assumed the most expansive view of individual rights against the government (supporting rights claimants nearly 70 percent of the time).

Commitment to Public Service

Although I should acknowledge that my appraisal of Justice Stevens’ contributions similarly assumes a civil libertarian perspective and may betray my own social or political bias, Justice Stevens himself seems to have struggled little with maintaining neutrality on the bench.

His many years of service reflect incredible commitment to the court, motivated by dedication in public service rather than pursuit of personal aims. According to Justice Stevens, the government has a “very strong obligation to be impartial,” with the judiciary providing much-needed oversight of executive and legislative power in running the country. Famously dissenting in Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98, which stayed a manual recount of Presidential election votes despite a lower court’s order that it proceed, he forcefully concluded that the ruling revealed:

an unstated lack of confidence in the impartiality and capacity of the state judges […] It is confidence in the men and women who administer the judicial system that is the true backbone of the rule of law. Time will one day heal the wound to the confidence that will be inflicted by today’s decision. One thing, however, is certain. Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year’s Presidential election, the identity of the loser is perfectly clear. It is the Nation’s confidence in the judge as an impartial guardian of the rule of law.

Justice Stevens’ impassioned support for the original trier’s finding dutifully recognizes the judiciary’s responsibility to neutrally arbitrate disputes, uphold constitutional principles, and thereby facilitate the democratic process. In discharging his own judicial duty, he frequently considers a variety of mitigating social, political, and cultural factors –quite uniquely including the narrative arc of American history– informing the interests at play in his opinions. These, in turn, are marked by decisive analysis, thoughtfulness, and characteristic curiosity. In my view, he possesses a remarkable toughness in his sensitivity to all parties engaged by his work.

In Sum

Perhaps appreciating the current composition of the court and his own strong positions on a variety of issues, Justice Stevens’ recently commented in cheek, “I suppose there are a lot of people out there praying I get out of the way.” If he does indeed retire before the 2010/2011 term, it will be a most considerable loss to the U.S. Supreme Court. May we anticipate the news that Justice Stevens will continue to serve for years to come.

Join the conversation