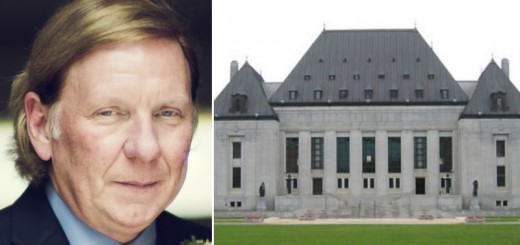

Whose moral compass is it anyway? Judge Matlow’s case

A five member Inquiry Committee responding to a complaint against Justice Ted Matlow of the Superior Court of Ontario reported to the Canadian Judicial Council (CJC) on May 28, 2008 that there are grounds to justify making a recommendation for the removal of Mr. Justice Marlow from judicial office. (The Inquiry Committee’s report is available on the Council’s website.)

The complaint arose from an October 2005 Divisional Court proceeding in which Justice Matlow ruled against the city of Toronto in SOS- Save Our St. Clair Inc. v. City of Toronto and Toronto Transit Commission. The case was initiated by a neighborhood group (SOS) hoping to block the city and the Toronto Transit Commission from implementing a reconstruction project of existing street car tracks on St. Clair Avenue West. Shortly after, Toronto city solicitor, Anna Kinastowski, filed the complaint to the CJC on January 31, 2006 requesting an investigation of Justice Matlow’s actions and seeking his removal from office pursuant to subsection 63(2) of the Judges Act, R.S.C. 1985 c. J-1.

The actions under review include Justice Matlow’s activities, from 2002 to 2004, with an ad hoc neighborhood group called “Friends of the Village.” The group was campaigning to stop the “Thelma project,” which involved a mixed-use residential, commercial and parking complex at the intersection of Spadina Road and Thelma Avenue; the street where Justice Matlow resides.

A panel was constituted in accordance with the CJC Complaint Procedures and after deliberating, it recommended an inquiry committee be held. On April 3rd, 2007, the CJC constituted an inquiry to investigate the complaints’ against Justice Matlow’s conduct. The allegations made in the complaint included:

1) organizing and leading the group opposing the Thelma Project;

2) meeting and corresponding with politicians;

3) using his title “Justice” in connection with the activities;

4) promoting news media involvement in the controversy;

5) using intemperate language and inappropriate comment;

6) sitting on an application concerning street use in which the City was a party (the “SOS Application”) and which involved a local group opposing a municipal development;

7) failure to disclose to counsel and his judicial colleagues the extent of his previous involvement with the Thelma Project controversy.

8) The complaint also made allegations concerning Justice Matlow’s promotion of renewed media interest into his allegations of municipal misconduct respecting the Thelma Project related actions more than a year after the original controversy came to an end, when he knew he would be presiding over the SOS Application.

The ethical standards used to scrutinize Justice Matlow’s conduct were amalgamated from a variety of sources which were advisory in nature. The Inquiry Committee however, grounded its conclusions on an assessment of one fundamental duty to maintain public confidence in and respect for the rule of law. This obligation demands that judges “project an image of integrity, impartiality and good judgment”. [para 126] This means that “[i]t is important, therefore, for a judge to give some thought to how his or her conduct would be perceived by those reasonable, fair minded and informed persons” [128]. On this basis, the Inquiry Committee determined the duty to maintain public confidence precludes a judge from having “any known association with or even attendance at a public gathering involving a politically controversial issue”, because it could “reasonably put in question the judge’s impartiality on an issue that could come before the court” [135].

In its analysis of Justice Matlow’s conduct, the Inquiry Committee found that his “personal involvement in opposing the Thelma Project went considerably beyond what was appropriate for a judge” [150] Indeed,

Justice Matlow’s overall conduct in organizing and leading The Friends, his assumption of the role of the president, spokesperson, and on occasion, advocate of The Friends, his conduct in seeking to personally be a party and as a result being made party in the OMB application of First Spadina, his conduct in providing guidance, advice and assistance in the application by some members of the Friends to the Superior Court of Justice, and his conduct in assisting in preparation of the supporting affidavit to which was attached copies of letters from him to the Mayor of the City and the Attorney General of Ontario, constitutes conduct that is highly inappropriate for a judge [152].

As such, the inquiry concluded that Justice Matlow has “placed himself, by such conduct, in a position incompatible with the due execution of that office” [153].

As for using the title of “Justice” in connection with these activities, the Inquiry Committee found that doing so was “inappropriate and served to diminish the confidence of the public in the impartiality of both Justice Matlow personally and the judiciary generally” [159]. Even though this behavior did not amount to “misconduct” within the meaning of para 65(2)(b) of the Judges Act, it was weighed with the general activities above as additional grounds to conclude that Justice Matlow placed himself in a position incompatible with the due execution of his office.

In assessing the involvement of the news media, the Inquiry Committee seemed mostly offended by the “strident language” to which they quoted Justice Matlow describing the Thelma Project as an “absurd proposal” with “elements of stupidity, political intrigue, and, perhaps, dishonesty” [161]. As a result, this conduct placed Justice Matlow in a position incompatible with the due execution of his office [162]. Similarly on the individual allegation of using intemperate language and inappropriate comment, the Inquiry Committee found the judge committed “serious impropriety amounting to judicial misconduct” [169]. In this regard, the Inquiry Committee did not indicate the meaning or extent of the standard of “intemperate language and inappropriate comment” but nevertheless found Justice Matlow committing those in his email exchanges and on cross-examination.

The Inquiry Committee then analyzed the allegation that Justice Matlow failed to take steps to avoid potential conflicts. The Inquiry Committee concluded from the evidence provided by Justice Matlow, that he did not believe he was in a conflict of interest situation nor did he believe that a reasonable, fair minded and informed person would have a reasoned suspicion of conflict [170]. However, the Inquiry Committee found that he could not but have concluded that a reasonable, fair minded and informed person would perceive a reasoned suspicion of conflict and as such he failed in the due execution of his office as a judge because he did not excuse himself from any case involving the city [172-173]. As a result, the Inquiry Committee further found that he failed with the due execution of his office by a combination of not disclosing the extent and nature of his involvement with The Friends, to the counsel involved in the SOS Application and the other two panel judges, and additionally by failing to take steps to ensure he did not sit on the SOS Application [187].

Finally, Justice Matlow’s promotion of renewed media interest (by writing to John Barber of The Globe and Mail) into his allegations of municipal misconduct respecting Thelma Project when he knew he would be presiding over the SOS Application placed him, according to the Committee, in a position incompatible with the due execution of his office. The limited expression of regret by Justice Matlow in his testimony portrayed to the Inquiry Committee no change in view as to the propriety of his conduct and so, with the totality of their findings, he was found incapable of performing the duties of his judicial office. The recommendation of the Inquiry Committee to the CJC was the removal of Justice Matlow from his office.

Justice Matlow’s counsel Paul Cavalluzzo of Toronto’s Cavalluzzo Hayes Shilton McIntyre & Cornish LLP and his co-counsel Fay Faraday highlighted to Lawyers Weekly that the issue is about the “boundaries of acceptable free speech and association by judges in their capacity as private citizens.” The Inquiry Committee responded to this Charter argument by framing the issue as not a limitation of a Charter right but instead a matter of the “normal duty of a judge” [119]. One has the choice to “insist on the right to continue to assert an uninhibited manner the full Charter rights of every citizen” and “not be appointed as a judge” [120]. Basically, it is a limitation of a Charter right, but it is not called that. In all regards, the committee saves this breach (if it was found so) as justified in “a free and democratic society to ensure the preservation of the impartiality and independence of the judiciary and the rule of law” [122].

It is important to locate the standards that Justice Matlow is being held to. It is understood that the CJC’s sole publication on Ethical Principles of Judges is not a list of prohibited behaviors nor is it a standard to define misconduct. There are no firm guidelines or rules, which Justice Matlow broke. The Inquiry Committee’s findings are based on a common law tradition of deduction; one rule from this judgment, another bit of obiter from that. In a way, the guidelines and rules were being created through this Inquiry. Their objective, they mention, is not to punish a party, but to preserve the whole [106]. Regrettably, in this case as many others, the law is born at the expense of people’s lives, jobs and reputations.

It is also important to assess the standards used by the Inquiry Committee and for that purpose; the following is some food for thought:

-What is this concern with appearance of impartiality and independence? Does it not appear that the city looks authoritarian when complaining about a judge who decided against their case in one out of their five cases that came before him?

-What is it to be impartial? Does that exclude a judge’s civic duty to exposing possible corruption or illegality in an affair outside his court?

-What about a judge exposing possible corruption or illegality of actions by city employees (solicitors in this case), does that mean he is against or for the city?

-How about Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin’s statement that one cannot realistically expect judges to leave their values on the steps of the courthouse?

-Do we not expect judges to isolate their biases from their decisions? So why should we set up an inquiry to determine whether one’s political action (or ethnicity, gender or sexual orientation) places them in a position incompatible with the due execution of their office?

-Should judicial disciplining scare off judges from being open about their system of beliefs?

-Should an inquiry committee (comprised of 3 judges and two lawyers) decide the ethical standards of judges in dynamic and democratic societies?

-In the CJC inquiry of Justice Jean Bienvenue, a recommendation was made to have a “social context education.” Was Justice Matlow’s engagement in the public’s social context such an education? And was this education not worth the public’s good perception of the administration of justice?

Join the conversation