Google v Equustek: An Attempt to Domestically Govern a Global Resource

On June 28, 2017, the Supreme Court of Canada released Google Inc v Equustek Solutions Inc, 2017 SCC 34 [Google] which granted a worldwide interlocutory injunction against Google Inc. (“Google”), ordering it to remove a company’s website from its global search engines. The Court’s decision in Equustek provides new tools to intellectual property owners to protect their intellectual property rights, but it also has troubling implications for international governance of the Internet.

Factual Background

The proceedings date back to 2011, when Equustek Solutions Inc. (“Equustek”) sued its former distributor, Datalink Technologies Gateway Inc. (“Datalink”), for misappropriation of intellectual property. Equustek alleged that Datalink re-labeled Equustek’s products and sold it as its own and that Datalink had acquired confidential information and trade secrets belonging to Equustek, using them to manufacture a competing product, which increased Datalink’s sales at Equustek’s expense.

Equustek obtained several interlocutory injunctions against Datalink, including court orders prohibiting the sale of inventory, a ban the use of Equustek’s intellectual property, and a freeze on Datalink’s worldwide assets. Datalink ignored all the court orders and continued to conduct business through several different online websites from an unknown physical location.

With Datalink continuing to conduct business online, Equustek reached out to Google in 2012, requesting it to de-index Datalink’s websites or, in other words, to remove all links to Datalink-affiliated websites from its search engines. Following a court order, Google de-indexed 345 individual webpages from the Canadian google search engine (google.ca), but did not de-index Datalink’s webpages from its global domain (google.com). As a result, Equustek sought an interlocutory injunction to order Google to remove all of Datalink’s affiliated websites from its worldwide search engine. The Court in upholding the decisions of the British Court of Appeal and British Columbia Superior Court, granted the interlocutory injunction.

Decision Overview

Abella J. delivered the judgment of the Court. This post focuses on Google’s primary argument: the impropriety of issuing an interlocutory injunction with extraterritorial effect. Google challenged the global reach of the interlocutory injunction, suggesting that if the injunction is to be granted, it should be limited to Canada alone. The Court’s decision acknowledges the challenges of a global Internet order, but concludes that an international takedown is necessary to ensure that the interlocutory injunction is an effective remedy:

The problem in this case is occurring online and globally. The Internet has no borders — its natural habitat is global. The only way to ensure that the interlocutory injunction attained its objective was to have it apply where Google operates — globally. As Fenlon J. found, the majority of Datalink’s sales take place outside Canada. If the injunction were restricted to Canada alone or to google.ca, as Google suggests it should have been, the remedy would be deprived of its intended ability to prevent irreparable harm. Purchasers outside Canada could easily continue purchasing from Datalink’s websites, and Canadian purchasers could easily find Datalink’s websites even if those websites were de-indexed on google.ca. Google would still be facilitating Datalink’s breach of the court’s order which had prohibited it from carrying on business on the Internet. There is no equity in ordering an interlocutory injunction which has no realistic prospect of preventing irreparable harm.

The Court was not persuaded by concerns about the global injunction violating international comity, characterizing the concerns as “theoretical,” finding that “most countries would likely recognize intellectual property rights and view the selling of pirated products as a legal wrong.”

Implications for International Governance of the Internet

Internet jurisdiction and governance has presented, and will continue to present, an enormous challenge for the courts. For the most part, it is not technically hard or costly for an individual or company to comply with global court orders. The difficulty arises with the effects of the order. If courts in every country assert jurisdiction over the Internet, not only will the online sphere quickly become over-regulated with a myriad of potentially conflicting laws, but countries with more oppressive regimes may enact their own information-restricting laws for the Internet. If Canadian courts are able to require third-party online platforms to enforce Canadian law on a global basis, nothing prevents repressive regimes, with different conceptions of acceptable expression, from doing the same thing.

In an era where court orders to remove online content is on the rise worldwide, this presents a greater concern. A month before the Court released the Google decision, Germany passed a law that ordered social media companies operating in the country to delete hate speech within 24 hours of it being posted or to face fines up to $57 million. Earlier this year, an Austrian court similarly ruled that Facebook must take down hateful posts directed at the country’s Green party leader. The European Union’s top court is currently deciding whether its “right to be forgotten” laws should extend beyond Europe’s borders. The Equustek decision has already begun to be cited in foreign courts; recently, a Hong Kong court admitted a lawsuit of a local entertainment tycoon against Google for autocomplete suggestions on Google Search that allegedly damaged his reputation. The judge issued a global de-indexing order, citing the Google decision. There are dozens of other cases pertaining to global takedown requests that are pending.

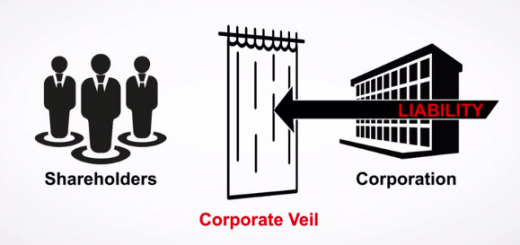

Another issue caused by the Google decision is its effect on comity. Comity is a principle of interpretation, not a rule of law, reflected in the Charter of the United Nations as “respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples.” It was defined by this Court in Morguard Investments Ltd. v De Savoye, [1990] 3 SCR 1077, to be “the deference and respect due by other states to the actions of a state legitimately taken within its territory.” Comity requires courts to avoid the appearance of or actual interference beyond their territorial limits, and, in return, other jurisdictions reciprocate with the same courtesy. If Canadian courts begin issuing global orders, then there is a real risk that other jurisdictions will not recognize Canadian judgments, especially if the issued order conflicts with the domestic laws of their jurisdiction, giving rise to further issues of enforceability. Thus, the Court’s global order poses a serious challenge to comity because it fails to respect the integrity and self-determination of other nations. By requiring Google to de-index all of Datalink’s websites from its search engines globally, the Court is determining what content is accessible to another nation’s citizens.

Not only does the Court’s decision have negative consequences for judicial comity, but the Court has shifted the burden of proof from the plaintiff to a non-party, by requiring Google to prove that the injunction violates the law of another nation, in order to have the global court order modified:

Google’s argument that a global injunction violates international comity because it is possible that the order could not have been obtained in a foreign jurisdiction, or that to comply with it would result in Google violating the laws of that jurisdiction, is theoretical … If Google has evidence that complying with such an injunction would require it to violate the laws of another jurisdiction, including interfering with freedom of expression, it is always free to apply to the British Columbia courts to vary the interlocutory order accordingly.

One can reasonably argue that most of the Internet is controlled by a few multinational corporations, such as Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon and Microsoft. Most of these multinational corporations will be able to afford the litigation costs of showing that the injunction violates another country’s laws. Further, placing the litigation burden on these multinational corporations could result in a more efficient economic outcome. If multinational corporations are burdened with the legal burden of proving illegality of the injunction on a country-by-country basis, they would gain economies of scale as they familiarized themselves with domestic laws. The contrasting situation, where a plaintiff would bear this burden on every occasion, is economically inefficient.

These arguments are not without their fallacies. Even though control of the Internet is heavily concentrated in the hands of a few multinational corporations, to shift the litigation burden of proving a violation of comity onto these companies will stifle innovation and discourage economic competition. In the end, greater concentration will only harm consumers globally through price increases and service limitations. More troubling is the fact that an innocent third party to a lawsuit has been burdened with the responsibility of proving an injunction violates the law of another country.

This is not to suggest shifting the legal and litigation burden onto the plaintiff would be a better outcome. It is not. The ideal outcome would be to eliminate the legal and litigation burden completely through legislative reform, whether that entails international regulation of the Internet or domestic legislative reform. The purpose of litigation should not be to give birth to further litigation. Litigation seeks to resolve claims. If litigation is compounding the issue, then the answer to the problem must include a component of legislative reform.

A further consequence of the Google decision is that it may give rise to forum shopping. Forum shopping is the practice of seeking the court where a litigant may expect the court to provide a favourable judgment. Plaintiffs like Equustek may seek out the courts most willing to grant a global court order even where jurisdictional ties are tenuous, such as Canadian courts, and non-parties like Google will challenges these orders in jurisdictions with more stringent technology laws. Forum shopping may be limited by many common and civil law’s countries regulations on standing, but in this case, Google has already filed an injunction with the U.S. District Court for Northern California in late July 2017, submitting that the Canadian court order violates U.S. law and Google should not be forced to comply with the Canadian ruling. We are already seeing the tension that the Google decision has created on international relations and the principle of comity.

Looking Forward

Internet jurisdiction raises difficult questions about regulation and governance. The answers to these problems should not come from the common law, but rather from legislative reform. The problems that would occur with every country governing the Internet with potentially conflicting laws and over-restrictive laws for the Internet, would come at the cost of the fundamental rights of freedom of expression and freedom of information. The Internet has no national borders and should not be governed by any one country or any one court.

For further commentary on the Google v Equustek decision, please see the post by theCourt’s Irina Samborski.

Join the conversation