The Corporate Veil Comes at a Cost: Shareholder Claims Against Third-Parties

In Brunette v Legault Joly Thiffault, 2018 SCC 55 [Brunette], the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) clarified a long-standing rule that bars shareholders from bringing a cause of action against a third party for faults committed against a corporation in which they hold shares. In doing so, the Court also reconciled corporate law principles from common law and Quebec civil law on the matter.

Background

Facts

Group Melior was a group of corporations that owned and operated seniors’ residences, whose only shareholder in 2004 was Fiducie Maynard (“Fiducie”). In 2010, many of Group Melior’s corporations went bankrupt due to its vice-president’s fraud worth $1.8 million, plus an unexpected audit by Revenu Québec and accompanying collections action. These bankruptcies resulted in the complete loss of Fiducie’s property, which was comprised exclusively of shares in Group Melior’s holding company. The appellants, Yves Brunette and Jean M. Maynard, acting as trustees of Fiducie, sought to recover the loss of the patrimony from the respondents, a group of lawyers and accountants, including Legault Joly Thiffault (“LJT, et al”). Mssrs Brunette and Maynard claimed that the respondents committed various faults in setting up the tax structure of Group Melior, and therefore breached their duty to advise Fiducie.

Court of First Instance

In the Superior Court of Quebec (“QCCS”), the respondents moved to dismiss the action for lack of “sufficient interest.” It argued that Fiducie, as the sole shareholder of a holding company that was itself a shareholder of Group Melior, could not assert a right of action that only belonged to Group Melior corporations. Justice Mayrand of the QCCS agreed, citing Houle v Canadian National Bank, [1990] 3 SCR 122 [Houle], to find that shareholders only have sufficient interest to bring a claim against a third-party, such as the respondents, if that third party breached a legal duty owed directly to the shareholder and if the shareholder suffered damages distinct from any suffered by the corporation. Since the respondents allegedly committed wrongdoing against the Group Melior corporations, but did not breach a distinct legal obligation to the shareholder Fiducie, who had failed to claim an injury distinct from that suffered by Group Melior, Fiducie did not have a cause of action against LJT, et al.

Appeal

The Quebec Court of Appeal (“QCA”) unanimously upheld Justice Mayrand’s dismissal of Fiducie’s claim for lack of sufficient interest. The QCA that under both the civil law of Quebec and the common law, shareholders of a corporation have no cause of action for wrongdoing against the corporation. The QCA re-emphasized that this general rule is subject only to the Houle exception, which Justice Mayrand had applied at the QCCS. The QCA held that the Group Melior corporations or their trustees in bankruptcy had a right of action against the respondents for damages, but the fact that Group Melior had not initiated proceedings did not give Fiducie the right to bring its own claim against LJT, et al.

SCC Decision

Fiducie appealed to the SCC, where the Court was called on to answer whether the courts below erred in dismissing Fiducie’s claim for lack of sufficient interest. To do so, the Court first examined the procedural rules of standing. The Court then applied corporate law principles that limit the rights of shareholders to seek compensation for wrongdoing against the corporation in which they hold shares.

Standing Rules

According to the Quebec Code of Civil Procedure, C-25.01 (“CCP”), a party must have a sufficient interest in the claim in order to bring a cause of action (art 85). In Jeunes Canadiens pour une civilisation chrétienne v Fondation du Théâtre du Nouveau-Monde, [1979] CA 491, the QCA provide provided guidance on the meaning of “sufficient interest,” finding that it must be “direct and personal” (439). Expanding on this definition, the SCC has elaborated that the interest must be “legal, direct, personal, acquired and existing” (Noël v Société d’énergie de la Baie James, 2001 SCC 39, paras 37- 38). The SCC reiterated this interpretation in Brunette, further stipulating that the “direct and personal interest” cannot “be premised on another party’s right of action” (para 14).

A court will not presume the existence of a sufficient interest, and it is up to the claimant to allege the facts necessary to show a direct and personal interest. As such, the defendant can challenge sufficiency of the interest in order to dismiss the action at the preliminary stage. In this case, the respondents moved to dismiss Fiducie’s claim on the basis that, as an indirect shareholder of Group Melior, Fiducie has no right to claim losses equivalent to the real estate assets that had belonged to Group Melior. In order to determine the sufficiency of Fiducie’s claimed interest, the Court turned to the rules of corporate law.

Corporate Standing

It is a long-established rule in corporate law that a shareholder cannot recover for faults committed against a corporation (Foss v Harbottle, (1843) 67 ER [Foss]). The rule has been applicable in Quebec since Dominion Cotton Mills Company Limited v Amyot, [1912] AC 546 (UK JCPC). Nevertheless, the appellants argued that the common law rule set in Foss is incompatible with basic principles of the Quebec Civil Code, CCQ-1991 (“QCC”). The SCC disagreed, noting that:

In certain cases, the civil law produces a conclusion similar to that which would arise under the common law. This is one such case…This similarity, where it is premised on principles proper to each legal system, in no way detracts from the coherence and integrity of either. (para 14)

To illustrate, Justice Rowe, writing for the majority, cited the QCC’s recognition that corporations have a distinct legal personality (art 298) and a distinct patrimony (art 302), as well as the same enjoyment of civil rights as all legal persons (arts 301, 303). Reading these provisions together, Justice Rowe concluded the that QCC supports the Foss principle that “the right of action of a corporation belongs to the corporation itself” and “shareholders may not personally exercise a right of action that belongs to the corporation” (para 25).

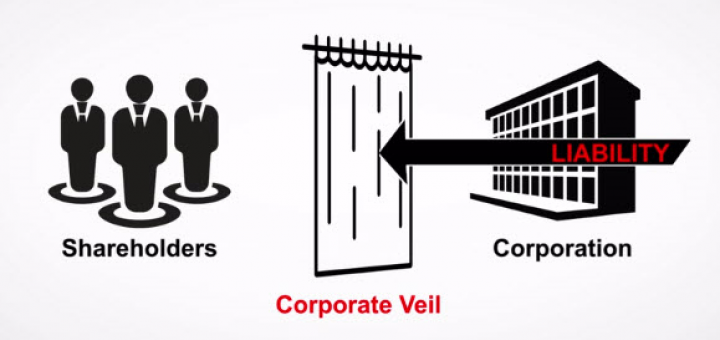

The Court stepped back to the rationale behind incorporation, which is premised on the benefit of limiting shareholder liability. However, this benefit comes with a corresponding limit on shareholder rights as the “corporate veil is impermeable on both sides” (para 27). Indeed, it would be inconsistent—and manifestly unjust—if shareholders were shielded from the corporation’s liability while at the same time enjoyed a right of action for wrongdoing to the corporation.

The Houle “Exception”

In Houle, the SCC reaffirmed the Foss rule, highlighting that in most cases where faults are committed against a corporation the shareholders suffer only an indirect injury, and so have no cause of action., The SCC, however, recognized that in rare circumstances shareholders “may possess their own right of action” (para 29, emphasis in original) if they can demonstrate that (1) they were owed an obligation distinct from the corporation, and (2) that a breach of this obligation resulted in a direct injury to the shareholders, independent from that suffered by the corporation. Justice Rowe insisted that Houle did not create an exception to the Foss rule, but rather “reiterated the essential elements of civil liability” that there must be direct fault, injury, and causation (para 30). Since the QCC allows for only the recovery of damages for direct injuries (art 1607), the Court found the common law principles in Houle, barring shareholders for recovering damages for indirect injuries, to be completely compatible with Quebec civil law.

Application of Houle

Under the first branch of the Houle test, the appellants argued that the respondent lawyers and accountants had contractual relationships with both Fiducie and Group Melior and had committed contractual and extra-contractual faults against Fiducie, which related mostly to the flawed tax structure of Group Melior. The Court found there were legal obligations owed to Group Melior, that the Group had failed “to show how the respondents owed an independent obligation to inform and advise Fiducie itself on the tax structure” (Brunette, para 38). The Court noted that injury to Group Melior would have consequences to those holding shares, especially to Fiducie as its sole shareholder, but this is only an indirect injury. Likewise, Mr. Maynard as the trustee and main beneficiary of Fiducie, was undoubtedly affected by faults committed against Group Melior. But Justice Rowe expressed little sympathy for his inability to bring action:

[H]aving chosen to structure his business by means of various incorporations, he cannot now seek to avoid the consequences of those choices ‘… he should not be allowed to escape its burdens. He should not be permitted to ‘blow hot and cold’ at the same time.’” (para 39, citing Kosmopoulos v Constitution Insurance Co, [1987] 1 SCR 2)

As for the second part of the Houle test, the appellants claimed damages corresponding to the loss of senior residences owned and operated by Group Melior. As the only shareholder in Group Melior, Fiducie eventually suffered bankruptcy, but the direct injury caused by the respondents was the loss of Group Melior’s property, making Fiducie’s suffering indirect.

The SCC agreed with the lower courts and found that Fiducie lacked sufficient interest to bring a cause of action against the respondents. The Court dismissed the appeal with costs to LJT, et al.

Dissent

Justice Côté agreed with the majority on the general Foss principle of the “distinct legal personalities of corporations and their shareholders” and that the common law and Quebec civil law are “much the same” on this point of corporate law (para 76). However, she parted ways with the majority’s reading of Houle, which she insisted requires no more than Justice Mayrand had found, namely that the damage be direct and personal. Justice Côté criticized the majority’s emphasis on the “distinctness” of the damage with being confusing, and notes that “a shareholder’s damage cannot be completely dissociated from that of the corporation” (para 82).

Fiducie claimed that it suffered direct damage as a result of a breach of a distinct duty owed by the respondents, which is a question of fact that a trial judge should refrain from deciding at the preliminary stage, according to Justice Côté. She noted that procedural rules allow an action to be dismissed at the preliminary stage, and that the proper administration of justice sometimes requires that. However, Justice Côté also insisted that this “drastic remedy” is available “only if it is clear that the plaintiff has no interest” (para 62, emphasis in original). In this case, Justice Côté found that it was not clear that Fiducie’s had no interest and Fiducie’s claim was a matter requiring trial and consideration of all the evidence, noting: “Fiducie may well have difficulty proving a sufficient interest at trial, but it should nonetheless be given the opportunity to do so” (para 105).

Last Thoughts

The corporate veil is a powerful tool that has protected countless shareholders from the misdeeds of corporations. Therefore, it is only fair that the veil, while shielding shareholders from the corporation’s liability, would create a barrier on both sides and also prevent shareholders from exercising the corporation’s legal rights. If LJT, et al had indeed owed a separate duty to and committed fault against Group Melior, then I am in full agreement with the majority that Fiducie cannot benefit from the limited liability of corporation and still hope to enjoy the corporation’s right to bring action. However, since Fiducie was the sole shareholder and there are factual ambiguities as to the obligations the respondents owed to Group Melior versus Fiducie, I agree with Justice Côté that it is not entirely clear that Fiducie had no direct interest. Although it is likely that the respondents would not be found liable to Fiducie, I also agree with Justice Côté that “there is nothing trivial about dismissing an action before the plaintiff has even had an opportunity to be heard on the merits” (para 55) and the appellants’ action should not have been dismissed at the preliminary stage.

Join the conversation