2018 at the Supreme Court: A Year in Review

TheCourt.ca is pleased to present its annual Year in Review for 2018. In this post, TheCourt staff authors analyze statistical trends among all the decisions released by the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC” or “the Court’) in the last year (see also our coverage of 2015, 2016 and 2017).

While no year is ever dull at the Supreme Court of Canada, in which the majority of appeals require leave (permission) from the Court to be heard, 2018 was especially memorable. In June 2018, the Court released the widely anticipated Trinity Western cases (Law Society of British Columbia v Trinity Western University, 2018 SCC 32 and Trinity Western University v Law Society of Upper Canada, 2018 SCC 33, collectively “Trinity Western”), in which the Court was asked to resolve a “clash” of Charter rights between the equality interests of the LGBTQ+ community and freedom of religion of an evangelical Christian university. Shortly thereafter, the Court released Reference re Pan-Canadian Securities Regulation (2018 SCC 48), which finally gave the constitutional go-ahead to Parliament to begin developing a national securities regulator. The Court also struck down mandatory victim surcharges in R v Boudreault (2018 SCC 58), confirmed that the Constitution does not mandate free trade within Canada (R v Comeau, 2018 SCC 15), and refined the legal framework for production orders against confidential journalistic sources (R v Vice Media Inc., 2018 SCC 53).

In 2018, the Court also vindicated the decade-long plight of Joseph Groia, Toronto securities litigation counsel and a Law Society of Ontario bencher, who fought a finding of professional misconduct from the Law Society Hearing Panel all the way to the highest court. (See TheCourt’s coverage – including input from Mr. Groia – here). In Groia v Law Society of Upper Canada (2018 SCC 27) [Groia], the Court found that the then-Law Society of Upper Canada erred in finding that Mr. Groia had engaged in professional misconduct while vigorously defending a client in a 2007 matter. According to the Court, trials are “often hard fought” and “are not tea parties” (Groia, paras 3 and 99), and it is appropriate lawyerly conduct to “raise fearlessly every issue, advance every argument and ask every question, however distasteful” to advance a client’s interests within the boundaries of the law (para 73). Incidentally, the claims of incivility against Mr. Groia stemmed from a notable case itself. R v Felderhof (2002 CarswellOnt 5623 (Ont. SCJ)) was the sole prosecution of a corporate executive emerging from the collapse of Bre-X Minerals Ltd., a Canadian mining company, the decline of which was spectacular enough to inspire a Hollywood film starring Matthew McConaughey (Gold).

Finally, in 2018 the Court dealt with two major cases related to Indigenous rights, Mikisew Cree First Nation v Canada (Governor General in Council) (2018 SCC 40) [Mikisew Cree] and Williams Lake Indian Band v Canada (Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development) (2018 SCC 4) [Williams Lake Indian Band]. Mikisew Cree is a landmark decision on the scope of the duty to consult with Indigenous communities where the Court found that the duty to consult does not extend to the legislative activities of Parliament. In the latter, Williams Lake, the Court held that the relationship between the Crown and Indigenous peoples is fiduciary in nature, even prior to Confederation, and that the Crown’s fiduciary obligation imposes certain restrictions on Crown decision-making.

In what follows, we produce and analyze relevant statistics relating to the batch of 59 cases the Supreme Court decided on last year, including stats on the Court’s workload, authorship trends, rates of dissents and concurrences, and more.

Number of Decisions Released

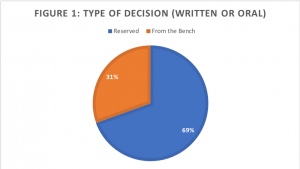

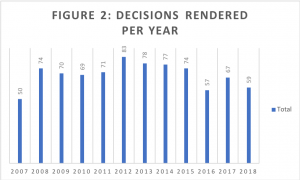

The SCC released 59 judgments in 2018, down from 66 in 2017 (see Figure 2).The mean average per year, however, varied only by one, down from 70 in 2017 to 69 in 2018. Of the 59 judgments released by the SCC in 2018, 18 (31%) were delivered orally (see Figure 1). This percentage is on par with the number of oral judgments in 2017 (30%). The vast majority of the 2018 oral judgments were for criminal appeals (16 or 89%). Only 5 (28%) of the 2018 oral judgments had intervenors, and all these cases had fewer than 5 non-parties giving submissions.

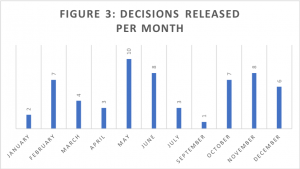

Additionally, 13 of the 18 oral judgments were unanimous, with only 5 dissents and no concurrences. While oral judgments are an efficient way for the SCC to dispense with straightforward appeals, too many oral judgments risks obscuring the reasoning behind the Court’s decisions, which in turn may hinder the development of jurisprudence. Rates of decision release per month are detailed in Figure 3. Judgement Lengths

Judgement Lengths

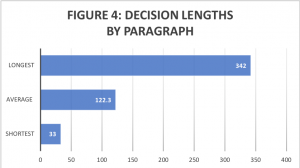

Figure 4 shows the average length of decisions released by the Supreme Court. In the shortest decision, R v Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (2018 SCC 5), Justice Brown, writing for a unanimous Court, clarified the RJR-MacDonald test for mandatory injunctions in a succinct 33 paragraphs. The Court’s longest decision of the year was Law Society of British Columbia v Trinity Western University, at 342 paragraphs. The widely publicized case on competing Charter rights (freedom of religion versus the right to equality) was written jointly by Justices Abella, Moldaver, Karakatsanis, Wagner and Gascon (106 paragraphs), with then-Chief Justice McLachlin concurring (44 paragraphs), Justice Rowe concurring in the result (107 paragraphs, the same length as the majority decision), and Justices Côté and Brown dissenting (82 paragraphs). The companion case, Trinity Western University v Law Society of Upper Canada, concludes at a significantly shorter 82 paragraphs. Trinity Western tops the longest judgement of both 2016 (R v Jordan 2016 SCC 27 at 303 paragraphs) and 2017 (R v Marakah 2017 SCC 59 at 200 paragraphs), both landmark cases in their own right. Its substantial length reflects the continuing division among Justices of the Court on the scope of freedom of religion and the role of Charter values in Charter jurisprudence.

The Court’s longest decision of the year was Law Society of British Columbia v Trinity Western University, at 342 paragraphs. The widely publicized case on competing Charter rights (freedom of religion versus the right to equality) was written jointly by Justices Abella, Moldaver, Karakatsanis, Wagner and Gascon (106 paragraphs), with then-Chief Justice McLachlin concurring (44 paragraphs), Justice Rowe concurring in the result (107 paragraphs, the same length as the majority decision), and Justices Côté and Brown dissenting (82 paragraphs). The companion case, Trinity Western University v Law Society of Upper Canada, concludes at a significantly shorter 82 paragraphs. Trinity Western tops the longest judgement of both 2016 (R v Jordan 2016 SCC 27 at 303 paragraphs) and 2017 (R v Marakah 2017 SCC 59 at 200 paragraphs), both landmark cases in their own right. Its substantial length reflects the continuing division among Justices of the Court on the scope of freedom of religion and the role of Charter values in Charter jurisprudence.

Divides

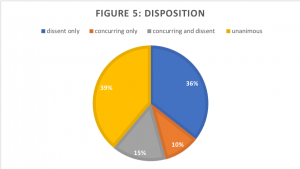

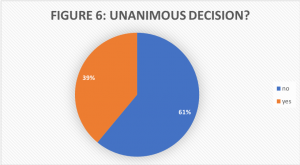

2018 marked a decrease from 2017 in the number of unanimous rulings reached on the Court. In 2018, only 23 of 59 cases (39%) heard by the Court were unanimously decided (see Figure 5), whereas in 2017 54% of cases were unanimous and 46% divided. When it did not rule unanimously, the Court’s reasons were more likely to feature only a dissent (21 of 36 non-unanimous appeals, or 58%). 9 out of 36 non-unanimous appeals (25%) featured both a dissent and concurring reasons, and only 6 of 36 appeals (17%) featured concurring reasons only. The increase in split decisions may indicate a period of transition on the Court from the consensus-oriented leadership of former Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin to a new status quo under Chief Justice Richard Wagner.

Of the unanimous judgments rendered in 2018, only two were written anonymously. By contrast, in 2017 the Court released three “By the Court” rulings, each of which were either one paragraph in length or a reiteration of a more significant decision. By contrast, the anonymous rulings rendered by the Court in 2018 were both significant and complex. R v Comeau was a highly anticipated federalism ruling, which queried whether section 121 the Constitution Act, 1867 imposed a requirement for free trade across provincial borders (the Court held that it did not). Reference re Pan‑Canadian Securities Regulation, the second anonymous decision, set the stage for the establishment of a long-awaited national securities regulation scheme in Canada. Both decisions bore hefty economic implications beyond the legal precedents set, and the fact that they were penned anonymously likely indicates that the Court wished to present a united front on the subject.

Certain scholars posit that high courts will offer anonymous rulings in order to present the decision as a single voice, and thus give it greater authority.[1] Alternatively, the attitudinal approach to judicial decision-making suggests that unanimity is only achieved when the political ideologies of each individual judge may be satisfied by the ruling.[2] Another view suggests that unanimous decisions arise out of an “informal collegiality” amongst judges, fostering consensus and compromise.[3] The latter consensus-driven model is certainly characteristic of the McLachlin court, and 2018’s decrease in unanimous decisions may therefore reflect the SCC’s change in leadership.

Statistics: Individual Justices

Figure 7: Decisions Written

| Justice | Majority |

Concurring |

Dissent | Total |

| McLachlin | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Gascon | 9 | 5 | 14 | |

| Wagner | 12 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| Côté | 4 | 6 | 13 | 23 |

| Brown | 8 | 2 | 7 | 17 |

| Moldaver | 10 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| Karakatsanis | 7 | 1 | 2 | 10 |

| Rowe | 6 | 7 | 8 | 21 |

| Martin | 1 | 1 | ||

| Abella | 9 | 3 | 2 | 14 |

| The Court | 2 | 2 |

Decisions Written/Authorship Trends

Figure 7 provides a glimpse into each justice’s rate of authorship in 2018. On average, each justice authored a median 12.3 judgments. Upholding her reputation from 2015, 2016 and 2017 as the Court’s most prolific author (and dissenter), Justice Suzanne Côté penned 23 independent judgments in 2018, over half of which were dissents. Writing at a rate of approximately 2.1 decisions per month (not including August 2018 when the Court did not release any decisions), Justice Côté wrote 9% more than 2018’s second-most prolific author, Justice Malcolm Rowe, and 43% more than 2018’s least prolific author, Justice Andromache Karakatsanis. (These calculations exclude former Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin and Justice Sheilah Martin, who left and joined the Court in December 2017, respectively.)

Notably, this year’s most prolific authors are relative newcomers to the Court. Justice Côté was appointed to the highest court in December 2014 and Justice Rowe in October 2016, making them the fourth and second newest members of the Court after Justice Martin (the newest member) and Justice Gascon (the third-newest member). The Court’s longest-sitting justices, Justice Abella (appointed in 2004) and Moldaver (appointed in 2011), penned their own decisions less frequently than the Court’s newer justices in 2018, preferring instead to join the majority in most decisions.

Figure 8: Participation in Judgment-Writing

Participation in Judgment-Writing

There are many reasons why individual justices may choose to pen their own decisions as opposed to joining the majority. Some authorship patterns may be related exclusively to the facts of the case, while others may indicate a preference on behalf of an individual justice to approach a legal issue in a particular way. Strong patterns of dissents and/or concurrences may indicate a desire on behalf of certain justices to signal that the legal issue at hand does not have a single answer, and to keep the door open for re-litigation in the future. Finally, low rates of agreement with majority reasons also allow individual justices to develop a distinct voice and body of jurisprudence within the broader context of Supreme Court rulings. While consensus is valued for the guidance it provides to lawyers and citizens, concurring and dissenting opinions offer valuable insight into the various approaches to answering novel legal issues.

Figure 8 also illustrates the likelihood that a particular justice would join or author a majority decision in 2018 rather than pen an independent concurrence or a dissent. The likelihood that a given justice will join a majority opinion is both context- and case-specific, but the statistics are notable for the patterns of consensus and coalition they may suggest among members of the bench. As in 2015, 2016 and 2017, Justice Côté was the justice least likely to join or author a majority opinion in 2018, agreeing with or penning the majority ruling in only 53% of decisions. Justice Rowe was second most likely to strike out on his own, joining the majority in 66% of cases, and former Chief Justice McLachlin was third most likely to deviate from the majority (73% majority likelihood in the cases she heard in 2018).

As Figure 8 shows, Justice Rowe was involved in the greatest number of decisions in 2018: He participated in 50 out of 59 judgments, or 85%. Closely trailing Justice Rowe in terms of participation were Justices Abella, Moldaver, Côté, and Brown, all of whom participated in 49/59 or 83% of decisions. Unsurprisingly given their transition periods onto and off the bench, former Chief Justice McLachlin and Justice Sheilah Martin participated in the fewest decisions in 2018. Nevertheless, the participation rate of each justice was quite high given the number of cases each heard: former Chief Justice McLachlin participated in 91% of the 24 cases she heard, while Justice Martin participated in 73%.

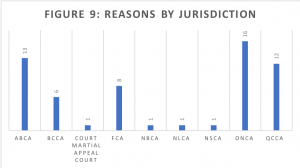

Reasons by Jurisdiction (Geographic Origin of Appeals)

Figure 9 illustrates the geographic origin of appeals for each decision rendered in 2018. While jurisdiction of origin does not correlate to the content of the decision to be reviewed, these stats reveal important information about the level of interaction between the Supreme Court and various provincial and territorial appellate courts. Given that the Supreme Court is a court of final appeal with national jurisdiction, and given the import of regional representation among the justices themselves, it is interesting to note patterns of regional representation among the cases that are heard.

In 2018, the SCC heard the most decisions from the Alberta Court of Appeal (ABCA) and the Court of Appeal for Ontario (ONCA), at 13 and 16 appeals respectively. The Court heard only six appeals from the British Columbia Court of Appeal (BCCA) in 2018, a marked departure from previous years, where considerably more appeals from BC were heard: In 2017, 18 appeals from the BCCA were heard and decided by the SCC, and 14 in 2016. It appears that there is a positive correlation between provincial population size and the number of cases heard by the provincial appellate court, so population size consequently impacts how many cases may go on to be heard by the Supreme Court. Given that British Columbia is one of Canada’s most populous province, the relatively low number of appeals emanating from the BCCA last year is notable.

Consistent with previous years, several Canadian jurisdictions had zero appeals heard by the SCC. In 2018, those jurisdictions were Manitoba, Saskatchewan, PEI, the Northwest Territories, the Yukon and Nunavut. Each of the Atlantic provinces except for PEI saw one appeal each heard by the SCC: from the New Brunswick Court of Appeal (NBCA), R v Comeau; from the Newfoundland Court of Appeal (NLCA), R v Normore (2018 SCC 42); and from the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal (NSCA), R v Cain (2018 SC 20). The SCC also heard one case from the Court Martial Appeal Court (CMCA), R v Gagnon (2018 SCC 41), a Charter matter flowing from a sexual assault allegation among military officers.

Regional representation of provincial appellate courts at the SCC was significantly more concentrated in 2018 than in 2017. In 2018, the SCC heard cases from seven jurisdictions, while in 2017 it heard cases from ten jurisdictions (not counting the Court Martial Appeal Court and/or the Federal Court of Appeal (FCA) in each data set). 2018 also saw a prominent increase in appeals from the FCA; notable decisions included Williams Lake Indian Band, Rogers Communications Inc. v Voltage Pictures, LLC (2018 SCC 38) and Mikisew Cree.

Timelines for Judgment Release

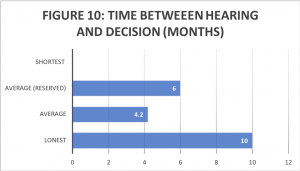

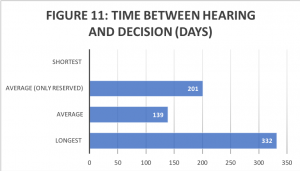

How long after presenting at the Supreme Court can you expect to have your judgement in hand? Figure 10 tracks the amount of time between oral argument at the Supreme Court and the release of the Court’s decision by month. (For those who are curious, the SCC itself provides data on the average timeframe between motions for leave being granted and oral arguments being heard. This information has not yet been updated to reflect 2018 data.) As a matter of convention, the SCC typically releases decisions within six months, or 180 days, of hearing arguments on appeal, but there seems to be no firm rule codifying this practice.

As Figures 10 and 11 show, the average wait time between oral argument and decision in 2018 was 139 days or 4.6 months. This timeframe is well below the six-month best practice, and is accounted for by the fact that the Court decided a full seventeen cases, mostly criminal as-of-right appeals, from the bench in 2018. Excluding oral decisions, the average wait time for a judgement to be rendered was 201 days or 6.6 months.

Followers of Churchill Falls (Labrador) Corp. v Hydro-Québec (2018 SCC 46) waited the longest for a decision in 2018: 332 days or 10.9 months lapsed between oral argument and judgment release in that case. The second-longest wait time for a decision was for Quebec (Commission des normes, de l’équité, de la santé et de la sécurité du travail) v Caron (2018 SCC 3) at 308 days, or just over ten months.

Little Change on Leave Applications

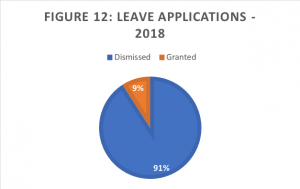

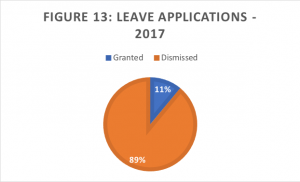

What is the likelihood that if your case will be heard at the SCC? As Figures 12 and 13 show, not very likely at all. There was not much variation between 2017 and 2018 in the percentage of appeals granted leave to the SCC. In 2017, the SCC granted (11% of applications) (see Figure 13) and in 2018, it granted 39 appeals (9% of applications) (see Figure 12). Notable cases that were granted leave include a case which will determine if multinational corporations can be held liable for alleged gross human rights violations committed by its subsidiaries overseas (Nevsun Resources Ltd. v Gize Yebeyo Araya, et al. – see TheCourt’s coverage of the case here), as well as the trio of appeals heard in late 2018 that will revisit the standard of judicial review post-Dunsmuir (Bell Canada, et al. v Attorney General of Canada, docket 37896; Minister of Citizenship and Immigration v Alexander Vavilov, docket 37748; and National Football League, et al. v Attorney General of Canada, docket 37897). Among the appeals denied leave included the case of James Forcillo, the Toronto police officer convicted of attempted murder in the death of Sammy Yatim (James Forcillo v Her Majesty the Queen, docket 38184).

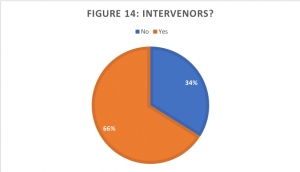

Intervenor Watch

As in 2017, this year we have kept an eye out for trends in intervenors appearing before the SCC. In 2017, intervenors participated in 41 of 66 (or 62%) of the judgments released. This rate remained fairly constant in 2018, in which 39 of 59 (66%) judgments included intervenors (see Figure 14). The number of intervenors per case varied: of the 39 judgments with intervenors, 67% (26) had between 1 and 9 intervenors, 23% (9) had between 10 and 19, and only 10% (4) had over 20.

Generally speaking, the SCC welcomes intervenors in acknowledgment that these groups bring value to the Court’s decision-making, particularly when the stakes of an appeal extend beyond the direct litigants. Consequently, granting leave to intervene on a given case is often framed as a matter of access to justice. But which groups have the resources to appear as intervenors? And for what kinds of matters? In 2018, the 4 cases decided by the SCC where over 20 intervenors participated suggest that the publicity of a case and the resources of the intervenors themselves play a role in how many external voices are represented. The case with the most intervenors in 2018 was R v Comeau with 32 intervenors, followed closely by Trinity Western University v Law Society of Upper Canada with 29 and R v Vice Media Inc. with 25. These three cases were high-profile, attracting both the public’s interest and the attention of many civic and religious groups (Trinity Western); media and press freedom associations (Vice Media); or commercial and industry interests (Comeau).

Constitutional and criminal cases, however, top the list of cases with intervenors (11 and 9 cases respectively). While all 11 constitutional cases had intervenors, only 9 out of 25 (8%) criminal cases had intervenors. This apparent underrepresentation may be explained by the fact that criminal law matters are heard as of right at the SCC, therefore not always satisfying the public interest test to intervene or gaining the publicity that engages interested parties. An examination of interventions from 2018 reveals that while both that high-profile cases garner broader interest and therefore more intervenors per case, the cases with the most intervenors still correspond to the most common types of matters heard by the SCC.

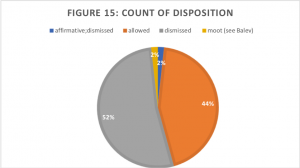

Disposition

In 2018, the rate of appeals allowed and dismissed varied slightly from 2017. This year, the SCC heard 59 appeals: It allowed 26 appeals (44%, up from 39% in 2017), dismissed 31 appeals (52%, down from 56% in 2017), heard one reference (2%), and ruled on 1 moot appeal (2%) (see Figure 15). Of the allowed appeals, 4 included appeals allowed in part: Delta Air Lines Inc. v. Lukács, 2018 SCC 2; Ewert v Canada, 2018 SCC 30; R v Suter, 2018 SCC 34; and 3091‑5177 Québec Inc. (Éconolodge Aéroport) v. Lombard General Insurance Co. of Canada, 2018 SCC 43 (here Éconolodge Aéroport’s appeal was allowed in part). In the Reference re Pan‑Canadian Securities Regulation, the first issue was affirmed and the second issue dismissed (this accounts for the affirmative/dismissed category in Figure 12). The SCC also provided a judgment in Office of the Children’s Lawyer v Balev, 2018 SCC 16, despite the appeal being rendered moot by the fact that the children in question had since been returned to Canada. Nevertheless, the SCC chose to rule on the case in order to clarify the application of the Hague Abduction Convention, which seeks to protect children who have been unlawfully abducted by a parent from one member country to another, in Canada.

Concluding Thoughts

2018 marked the beginning of a transition period on the Supreme Court from a bench led by former Chief Justice McLachlin to new Chief Justice Wagner. Whether and how the change in leadership will alter the output of the Supreme Court will take many years to observe. Nevertheless, this transition year has given some indications of what features may characterize the Court under Chief Justice Wagner. In 2018, the number of divides among the Justices of the Court differed significantly from divides in 2015, 2016 and 2017. While under former Chief Justice McLachlin, the Court’s judgments often emphasized consensus-building, this year saw a notable decrease in unanimous decisions. It remains to be seen whether this represents a new status quo or simply a period of transition before Chief Justice Wagner’s leadership style becomes more apparent. We look forward to analyzing the decisions released in 2019, and we hope you will join us for the 2019 Year in Review!

[1] Bzdera, Andre. “Comparative Analysis of Federal High Courts: A Political Theory of Judicial Review” (1993) 26 Canadian Journal of Political Science 3 at 25.

[2] Glendon Schubert, The Judicial Mind: The Attitudes and Ideologies of Supreme Court Justices, 1946–1963 (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1965).

[3] Donald R. Songer & Julia Siripurapu, “The Unanimous Decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada as a Test of the Attitudinal Model” (2009) 42:1 Can J Poli Sci 65.

Join the conversation