2017 at the Supreme Court: A Year in Review

TheCourt.ca is pleased to present its annual Year in Review special for 2017 (see also our 2015 and 2016 Year in Review posts). 2017 was particularly impactful for the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”): the Court heard heavily publicized cases in its fall session alone including Trinity Western University (Trinity Western University v Law Society of Upper Canada, Docket No 37209; Law Society of British Columbia v Trinity Western University, Docket No 37318), Groia v Law Society of Upper Canada (Docket No 37112), and The Queen v Comeau (Docket No 37398), and released the much-anticipated decisions of Ktunaxa Nation v BC, 2017 SCC 54 (read Part I of TheCourt.ca’s coverage here and Part II here), R v Marakah, 2017 SCC 59 (coverage here), R v Bradshaw, 2017 SCC 35 (coverage here), Douez v Facebook, 2017 SCC 33 [Douez] (coverage here) and Google Inc v Equustek, 2017 SCC 34 (coverage here).

In this post, we present and analyze statistical trends in the written judgments released by the SCC in 2017. The SCC itself has recently issued a thorough crunching of all its numbers from 2007 to 2017, which is well worth reviewing. To avoid duplication, we offer commentary on some of the more interesting statistical trends from last year. We have also compiled a series of helpful factoids and tidbits, including: How many paragraphs was the longest judgment released in 2017? If you argue a case at the SCC, on average how long will it take before judgment is rendered on your case? What is the likelihood that the judgment rendered will include a dissent? (Answer: likely.) And more!

Judgments of the Court

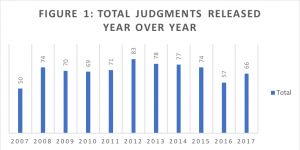

In 2017, the SCC released 66 judgments*, including both reserved judgments and judgments delivered orally from the bench. More judgments were released in 2017 in comparison to 2016’s low of 57 judgments, yet the number remains far below the peak of 83 judgments released in 2012. In his 2016 Year in Review post, John Mastrangelo pointed out that the SCC may be hearing fewer appeals because the legal questions that come before it are increasingly complex.

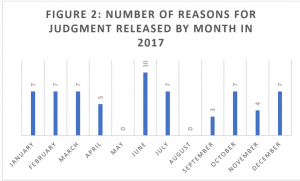

From 1 January to 31 December 2017, the SCC decided 66 appeals through 64 individually indexed reasons for judgment (Magoon v The Queen (Docket No 37416) [Magoon] and Jordan (Docket No 37479) [Jordan, 2017] were both decided orally from the bench with reasons to follow). Of the 64 released judgments, 19 were delivered orally from the bench. Figure 2 shows a breakdown of judgments released per month in 2017. The SCC released the most judgments in June (10), and the least number of judgments in May and August (zero).

2017 was a year of big changes for the SCC, but the numbers show that life at the highest court continues at a brisk pace. The SCC welcomed Justice Sheilah Martin in December, who filled a vacancy left by former Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin as she stepped down from her role and welcomed in new Chief Justice Richard Wagner.

Origin of Appeals

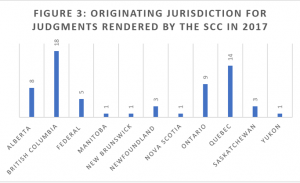

Figure 3 details the originating jurisdiction for each judgment rendered by the SCC in 2017. It comes as no surprise that the bulk of appeals came from some of the country’s most populous provinces, British Columbia and Quebec. Interestingly, the SCC only decided nine appeals originating from the Court of Appeal for O ntario (“ONCA”), the highest court of Canada’s largest province. The number of appeals flowing from the Alberta Court of Appeal (“ABCA”) also declined significantly this year: in 2016 the SCC decided 16 appeals from Alberta, while in 2017 it decided 8. Two jurisdictions – the Northwest Territories and Nunavut – had zero appeals heard last year by the SCC. The extent of regional representation differs from 2016, when no less than 7 Canadian jursidictions had zero appeals decided by the SCC: the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, PEI, and the Yukon (see the data here). While a number of factors are considered in deciding leave to appeal applications, including appeals as of right and the nature of the legal questions engaged, this year’s judgments include both complex legal issues and increased regional representation.

ntario (“ONCA”), the highest court of Canada’s largest province. The number of appeals flowing from the Alberta Court of Appeal (“ABCA”) also declined significantly this year: in 2016 the SCC decided 16 appeals from Alberta, while in 2017 it decided 8. Two jurisdictions – the Northwest Territories and Nunavut – had zero appeals heard last year by the SCC. The extent of regional representation differs from 2016, when no less than 7 Canadian jursidictions had zero appeals decided by the SCC: the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, PEI, and the Yukon (see the data here). While a number of factors are considered in deciding leave to appeal applications, including appeals as of right and the nature of the legal questions engaged, this year’s judgments include both complex legal issues and increased regional representation.

Disposition of Appeals

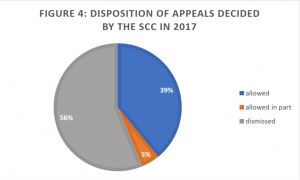

Of the 64 appeals for which judgment was rendered by the SCC in 2017, 25 were allowed and 36 were dismissed (see Figure 4). This is a significantly higher dismissal rate than the one clocked in after 2016, when the SCC split almost evenly on dispositions (48% allowed and 47% dismissed). Of the remaining appeals, 3 cases were allowed in part: Deloitte & Touche v Livent Inc (Receiver Of), 2017 SCC 63 [Deloitte], First Nation of Nacho Nyak Dun v Yukon, 2017 SCC 58 (the only case originating from the Court of Appeal of Yukon) and Teal Cedar Products Ltd v British Columbia, 2017 SCC 32.

Of the 64 appeals for which judgment was rendered by the SCC in 2017, 25 were allowed and 36 were dismissed (see Figure 4). This is a significantly higher dismissal rate than the one clocked in after 2016, when the SCC split almost evenly on dispositions (48% allowed and 47% dismissed). Of the remaining appeals, 3 cases were allowed in part: Deloitte & Touche v Livent Inc (Receiver Of), 2017 SCC 63 [Deloitte], First Nation of Nacho Nyak Dun v Yukon, 2017 SCC 58 (the only case originating from the Court of Appeal of Yukon) and Teal Cedar Products Ltd v British Columbia, 2017 SCC 32.

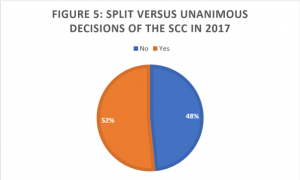

With or Without You: Unanimous & Split Judgments

The SCC ruled unanimously in 36 out of 64 (54%) of the cases it decided in 2017 (see Figure 5). Interestingly, the SCC rendered 3 judgments authored collectively by “The Court.” Two of these anonymous but unanimous decisions were one paragraph in length and the appeal was dismissed (see: R v Peers, 2017 SCC 13 and R v Aitkens, 2017 SCC 14). Notably, the third “By the Court” judgment, R v Cody 2017 SCC 31 is a 75-paragraph decision where the Court emphasized the framework established last year in R v Jordan, 2016 SCC 27 [Jordan]. Given the impact of the Jordan timeline for undue delay on criminal justice system operations, the “By the Court” authorship signals the Court’s commitment to the principles enunciated in Jordan.

Given that about half of the judgments released in 2017 were unanimous (a figure in line with the 2016 data), is the glass half full or half empty?

Depending on one’s perspective, the 2017 numbers may point towards increased consensus or increased division of opinion on the Court. A number of elements factor into the outcome of a case, especially at the appellate level. In the 19 decisions delivered orally from the bench in 2017, the Court often found sufficient legal reasoning in the lower level court majorities or dissents to simply concur with their judgments. These judgments typically consist of a single paragraph or two stating, “A majority of the judges of this Court agree with the reasons of the majority [or dissent] of the Court of Appeal. For these reasons, the appeal is dismissed” (see e.g., R v Savard, 2017 SCC 21), or similar phrasing. The numbers may also point to former Chief Justice McLachlin’s emphasis on consensus-building. Yet the significant rate of split decisions also demonstrates that there is debate and difference of opinion among the justices. It will be interesting to track this trend as Chief Justice Wagner – also known for his consensus-building abilities – takes leadership of the Court.

Depending on one’s perspective, the 2017 numbers may point towards increased consensus or increased division of opinion on the Court. A number of elements factor into the outcome of a case, especially at the appellate level. In the 19 decisions delivered orally from the bench in 2017, the Court often found sufficient legal reasoning in the lower level court majorities or dissents to simply concur with their judgments. These judgments typically consist of a single paragraph or two stating, “A majority of the judges of this Court agree with the reasons of the majority [or dissent] of the Court of Appeal. For these reasons, the appeal is dismissed” (see e.g., R v Savard, 2017 SCC 21), or similar phrasing. The numbers may also point to former Chief Justice McLachlin’s emphasis on consensus-building. Yet the significant rate of split decisions also demonstrates that there is debate and difference of opinion among the justices. It will be interesting to track this trend as Chief Justice Wagner – also known for his consensus-building abilities – takes leadership of the Court.

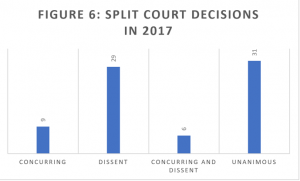

Divides

When the SCC did disagree this year, Figure 6 shows how the Court split. Collectively, the SCC justices were unanimous on 36 decisions (including Magoon and Jordan, 2017 decided in November 2017 with reasons pending). The justices parted ways in 31 decisions, with 9 decisions clocking in concurrences or concurrences in part, and 30 decisions recording dissents or dissents in part.

When the SCC did disagree this year, Figure 6 shows how the Court split. Collectively, the SCC justices were unanimous on 36 decisions (including Magoon and Jordan, 2017 decided in November 2017 with reasons pending). The justices parted ways in 31 decisions, with 9 decisions clocking in concurrences or concurrences in part, and 30 decisions recording dissents or dissents in part.

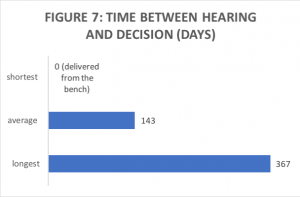

Timeline for Judgment Release

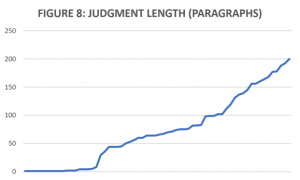

New to TheCourt.ca’s Year in Review data sets, this year we tracked when the decisions released in 2017 were heard and the average length between oral argument and the release of the judgment. (The SCC itself provides data on the average length between motions for leave being granted and when arguments are heard.) By convention, the SCC typically releases judgments within s ix months, or 180 days, of hearing the appeal. As Figure 7 shows, the average timespan between hearing date and judgment release in 2017 was 143 days, well below the six months mark – unless you are the parties in Ernst v Alberta Energy Regulator, 2017 SCC 1, who waited 367 days. This outcome was understandable given the complexity of the legal issues in that case: the decision, which dealt with Charter damages and administrative law, included three judgments and ran 190 paragraphs, one of the longest of 2017. Incidentally, this judgment was also the first released by the SCC in 2017, coming out on January 13, 2017. Typically, if a judgment was rendered from the bench, it reinforced the majority lower level decision in criminal, appeal as of right cases. By contrast, longer timespans between hearing dates and judgment releases tended to coincide with the complexity of the legal issue(s) and/or the number of opinions present in the decision.

ix months, or 180 days, of hearing the appeal. As Figure 7 shows, the average timespan between hearing date and judgment release in 2017 was 143 days, well below the six months mark – unless you are the parties in Ernst v Alberta Energy Regulator, 2017 SCC 1, who waited 367 days. This outcome was understandable given the complexity of the legal issues in that case: the decision, which dealt with Charter damages and administrative law, included three judgments and ran 190 paragraphs, one of the longest of 2017. Incidentally, this judgment was also the first released by the SCC in 2017, coming out on January 13, 2017. Typically, if a judgment was rendered from the bench, it reinforced the majority lower level decision in criminal, appeal as of right cases. By contrast, longer timespans between hearing dates and judgment releases tended to coincide with the complexity of the legal issue(s) and/or the number of opinions present in the decision.

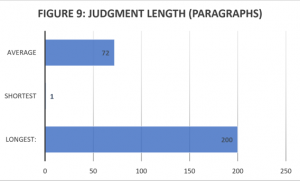

Once parties have their judgment in hand, what might they expect it to say? While the data can provide no insight into how the SCC will decide on a given case, it does tell us that the average length of a judgment rendered in 2017 was 72 paragraphs. On the low end of the spectrum, in 2017 the SCC released 9 decisions that were 1 paragraph long. All were delivered orally from the bench. Similar to length between hearing date and the release of a decision, the more complex the legal issues generally meant the Court would develop a longer decision.

The longest decision of 2017, R v Marakah, 2017 SCC 59, came in at just under 200 paragraphs and was written by then-Chief Justice McLachlin, with a concurrence by Justice Rowe and a dissent by Justice Moldaver (with Justice Côté concurring). This case was a well-publicized section 8 Charter challenge originating from the ONCA, in which the SCC found that the accused had a reasonable expectation of privacy over a text message sent to his accomplice’s phone and recognized a robust “zone of privacy” around electronic correspondence (see TheCourt.ca’s coverage here). Though it was the longest judgment of 2017, the length of Marakah pales in comparison to 2016’s longest decision, R v Jordan, 2016 SCC 27. Jordan came in at 303 paragraphs or 27,110 words (co-authored by Justices Moldaver, Karakatsanis, and Brown, with a concurrence by former Justice Cromwell). While both cases have had significant impact on the criminal law, Jordan fundamentally changed the face of the Canadian criminal justice system by imposing firm time caps on when an accused person may be brought to trial within a reasonable time pursuant to Charter section 11(b) – a topic that more than justifies its significant length.

decision of 2017, R v Marakah, 2017 SCC 59, came in at just under 200 paragraphs and was written by then-Chief Justice McLachlin, with a concurrence by Justice Rowe and a dissent by Justice Moldaver (with Justice Côté concurring). This case was a well-publicized section 8 Charter challenge originating from the ONCA, in which the SCC found that the accused had a reasonable expectation of privacy over a text message sent to his accomplice’s phone and recognized a robust “zone of privacy” around electronic correspondence (see TheCourt.ca’s coverage here). Though it was the longest judgment of 2017, the length of Marakah pales in comparison to 2016’s longest decision, R v Jordan, 2016 SCC 27. Jordan came in at 303 paragraphs or 27,110 words (co-authored by Justices Moldaver, Karakatsanis, and Brown, with a concurrence by former Justice Cromwell). While both cases have had significant impact on the criminal law, Jordan fundamentally changed the face of the Canadian criminal justice system by imposing firm time caps on when an accused person may be brought to trial within a reasonable time pursuant to Charter section 11(b) – a topic that more than justifies its significant length.

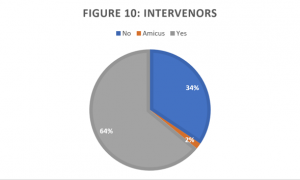

Intervenors

Another new addition to TheCourt.ca’s Year in Review roundup this year is a tracking of the number of judgments released in 2017 in which intervenors participated in the hearing(s) (see Figure 11). Out of 64 judgments released last year, 41 included intervenor participation. It is likely that the frequency of interventions s peaks to the importance of these cases to parties beyond the direct litigants, or to the legal system as a whole. Alternately, the frequency of interventions may reflect the complexity of the legal issues before the Court. The SCC is often asked to (re)consider legal tests or to develop doctrine in light of changing legal and technological landscapes (see, for example, Douez). In these types of cases, input from intervenors brings a valuable diversity of perspectives. From an access to justice perspective, intervening may also be the most meaningful opportunity for non-parties to participate in the legal process. On the other hand, a high number of intervenors in a given case may strain the Court’s resources – this was the issue in the recent controversy surrounding intervenors in the Trinity Western University hearing in the summer of 2017. Overall, the SCC has demonstrated a robust interest in hearing intervenors’ perspectives. Frequent intervenors in 2017 included the Canadian and British Columbia Civil Liberties Associations, the Criminal Lawyers’ Association of Ontario, and the David Asper Centre for Constitutional Rights based out of Toronto. The one amicus appearing in 2017’s judgments was Léon H. Moubayed, a partner at Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg LLP in Montreal, who appeared before the SCC in Desjardins Financial Security Life Assurance Co v Emond, 2017 SCC 19.

peaks to the importance of these cases to parties beyond the direct litigants, or to the legal system as a whole. Alternately, the frequency of interventions may reflect the complexity of the legal issues before the Court. The SCC is often asked to (re)consider legal tests or to develop doctrine in light of changing legal and technological landscapes (see, for example, Douez). In these types of cases, input from intervenors brings a valuable diversity of perspectives. From an access to justice perspective, intervening may also be the most meaningful opportunity for non-parties to participate in the legal process. On the other hand, a high number of intervenors in a given case may strain the Court’s resources – this was the issue in the recent controversy surrounding intervenors in the Trinity Western University hearing in the summer of 2017. Overall, the SCC has demonstrated a robust interest in hearing intervenors’ perspectives. Frequent intervenors in 2017 included the Canadian and British Columbia Civil Liberties Associations, the Criminal Lawyers’ Association of Ontario, and the David Asper Centre for Constitutional Rights based out of Toronto. The one amicus appearing in 2017’s judgments was Léon H. Moubayed, a partner at Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg LLP in Montreal, who appeared before the SCC in Desjardins Financial Security Life Assurance Co v Emond, 2017 SCC 19.

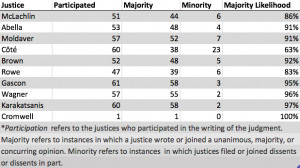

Statistics: Individual Judges

As Figure 11 shows, Justice Gascon was involved in the greatest number of decisions released in 2017: he participated in 61 of 64 judgments, or 95%. His participation rate is followed closely by those of Justices Côté and Karakatsanis, who are tied for frequency of participation at 60 judgments each (93.75%). Justice Rowe participated in the fewest judgments released last year, which is likely accounted for by the fact that he is a recent addition to the SCC.

Figure 11 also details whether a particular justice is more likely to join a majority or a dissent. Justices Karakatsanis and Wagner were most likely to join or author the majority opinion last year (97% and 96% likelihood respectively), and each justice dissented or dissented in part only twice. The new Chief Justice concurred twice on dissenting reasons in Teva Canada Ltd v TD Canada Trust, 2017 SCC 51 and Deloitte, while Justice Karakatsanis authored the dissent in R v Bingley, SCC 2017 12 at the beginning of the year and dissented in part in R v Boutilier, 2017 SCC 64 at the very end of 2017. Justice Suzanne Côté was the justice most likely to dissent in 2017, with the likelihood of her joining the majority decision sitting at 63%. Notably, of Justice Côté’s collective 23 dissents, 21 were full dissents, while one (Association of Justice Counsel v Canada (Attorney General), 2017 SCC 55) was a dissent in part, and the other (Deloitte) was a concurrence on Chief Justice McLachlin‘s dissent in part.

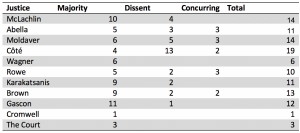

Figure 12 provides a glimpse into each justice’s rate of authorship and relationship to the written word. Justice Côté was the most prolific justice of 2017: she authored 4 majority decisions, 2 concurrences, and 13 dissents, bringing her total number of written reasons in 2017 to 19. Former Chief Justice McLachlin and Justice Moldaver, both senior justices on the Court, authored the next highest number of judgments, at 14 each. By contrast, the justice least likely to pen his own reasons was our new Chief Justice Richard Wagner, who wrote 6 majority opinions in 2017 and zero dissenting or dissenting reasons in part.

Conclusion

2017 was quite an intriguing year from statistical standpoint for the SCC. If you wish to view more data, the SCC also offers a fascinating breakdown of all its 2017 appeals categorized by types of law (43% criminal and 57% civil). Thank you for joining us for this year’s Year in Review roundup. Stay tuned for 2018!

* Note: R v George was first decided from the bench, but written reasons were also released at a later point in time. Nevertheless, we have counted it as one decision for the purposes of this review.

Join the conversation